But then someone said to me, it’s clear from your films that you put your whole self into them. I hadn’t realised that because I didn’t think I knew even a part of myself, let alone my whole self. And whenever I finished a film I felt that I’d only left a small trace. I needed to leave a trace, really I did. But my body’s tissue was still rotten.1

Saute ma ville (1968)

The intrusive eye roves with restless curiosity across domestic objects full of meaning, oblique movements—a humanity—unquiet and unafforded. Akerman sings out a frenetic piece: a self-destructive hum.

Every single intonation is unfilled, and the silence louder still. A scribbled note under a self-portrait pronounces: C’est moi!

She is always in control, on the edge, in-between. Judge Smurf exclaims “Go home” on a poster pinned on the closed kitchen door between outside and here. Where is home in Akerman’s oeuvre? The kitchen is flooded with water. 18-year-old Akerman as both character and director shines her shoes with black and then her legs too with casual mania. She holds the match to smell the gas to blow up all of cinema in her very first film.

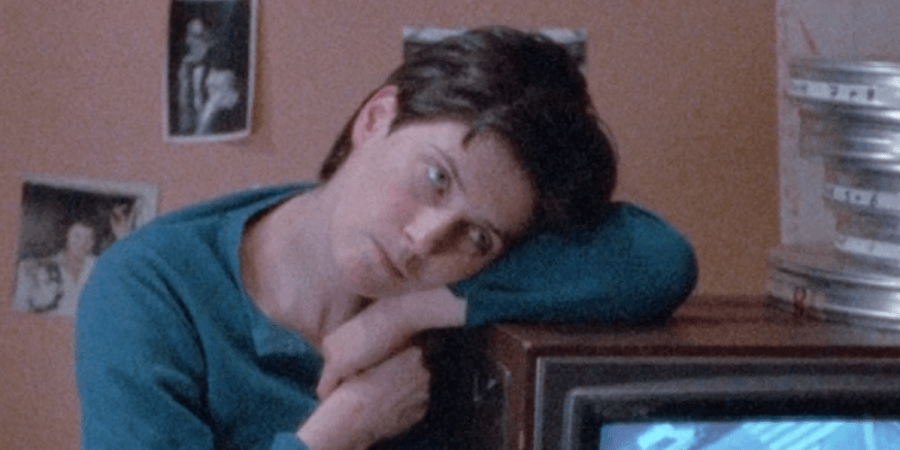

Je Tu Il Elle (1974) and La Chambre (1972)

To end on elle (she) is a radical departure—to first enunciate, and thus stake claim to, je (I). Mostly plotless, to give a précis may betray Akerman’s ambiguity. Open to interpretation, we follow the narrator Julie (Akerman, of course), who makes void the heterosexual expectation and all those associated scripts which muster her to he, before finally returning to, and spending an uninterrupted sex scene with she. In her first narrative feature, Akerman gives female desire and sexuality uninterrupted and monumental significance. Identification and labels, however, become suspect in Akerman’s cinema. “What the film enunciates,” writes Élisabeth Lebovici, “is not a difference, but a decentring of the enunciation, cracking the cultural cement.”2 She is separate, and then two bodies become one.

The urge to repaint the living space which holds one’s own concupiscent form. I can see myself so clearly sitting alone in the same bedroom, looking off into space, furiously writing letters, and eating bags of sugar. Then, the Sisyphean task of returning the sugar to the bag…

Suddenly: she addresses us. Audience! Witness and participate in this moving silent drama. The fourth wall, broken with restless despondency, aided by rotating camera, attends to the life collected on the edges of a bedroom, on the edges of boredom.

An aperture of blackness descends upon each take. Akerman re-arranges her body; a new orientation is offered to the audience. Her poses and gestures I often find myself in too.

Sugar granules on the floor. Haphazardly laying out hand-written love letters. Pinning these examples of your amour fou to the ground, lying prostrate, surrounded by memory. Akerman strips and places her clothes on top of her naked body. Waiting.

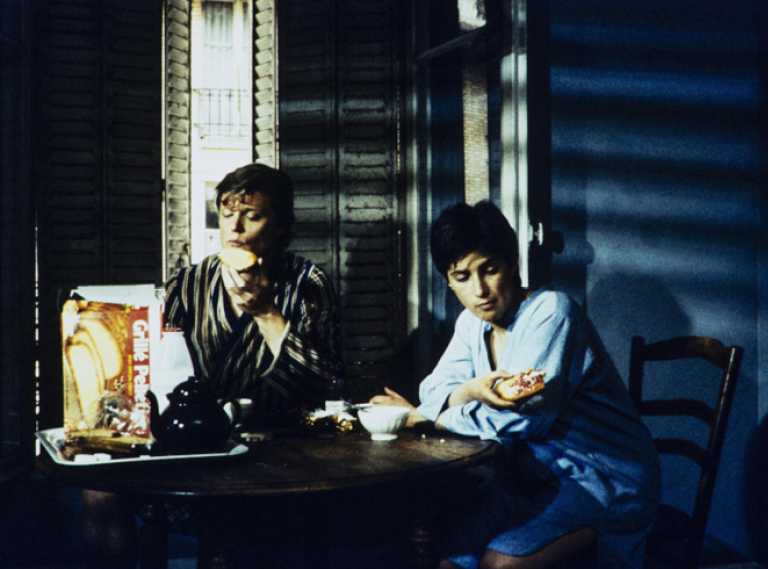

Eating dinner with the truck driver, mindlessly watching a television show; circus music makes farce out of the processes of heterosexual couplings. Rituals become redundant.

My brain works in fragments too. I, you, he, she.

Les Rendez-vous d’Anna (1978)

Giving parts of yourself away to others and to your art. The queer life-paths we take: what if I just settled down and had kids like everyone else? The ghostly image of Akerman reflected in the windowpane of the telephone booth of Anna’s missed call.

“One must forget the past,” but no one can stop talking about it.

“You’ve got to live somewhere,” so settle down and make a decision.

“I don’t like the suburbs,” you reply.

Akerman has always been drawn back to the city; the metropolis’ desire lines. Catch the train through a city’s arteries; open the hotel window to let air through its valves.

Sitting side-by-side: the confessional encounter allows for so much more intimacy than the face-to-face.

It all comes back to one’s mother in the end. But more on that in a moment.

D’Est (1993)

Somehow the most painterly of Akerman’s films. Snapshots of former Soviet territories, moments in time reminiscent of a Tarkovsky polaroid. How to show interiority only through screening exteriority?

Ethnographic in nature. Snapshots of rogue dogs, almost-empty bags of fruit. A sociality, a community, coming together through the rumble of punk music; the backlit mass of bodies moving through a Soviet city at night.

What will the next subject be?

The effort that unnarrated films ask of an audience: they poke holes into one’s mind (like a pinhole camera!). Thoughts begin to wander and are given the space to formulate anew. Her images return to me like camera obscura. Watching Akerman’s films is indeed work, as we experience the affective duration of life unfold on screen in real-time. Cinema that captures the process of ageing—like performance art in the way she engages / enrages / placates her subjects by placing her audience at arm’s length, refusing a linear narrative, revelling in an itinerant subjecthood, a transition, a perpetual state of movement.

Mapping out the space of thinking in gliding tableaux. Harvest, the gleaning. Pointillist landscapes with peppered snow-lit edges.

The audience’s gaze is unmoored from the constraints of linear narrative technique. It jumps from face to face, reading for emotions, searching for something to latch onto. When a filmed subject does return our gaze (thumbing us, smiling back, inquisitive or on the defense), giggles erupt at this site of sighted collectivity.

A people watcher’s film: imagine being forever immortalised on celluloid by Akerman, your worries and emotions of the day writ large on your face, forever in cinema. In history. The rare incursions into people’s heated homes. In a film as peripatetic as this, you begin to wonder which image Akerman will leave us on, her final shot, and always with surprise it hits you when it arrives.

News From Home (1976)

There is so much misery in this world and you young people see it so clearly. Hazy smog low over Hudson River’s peachy afterglow. I even dream about New York. Summer Manhattan rituals: a burst fire hydrant offers some respite. A Belgian accent on top of iconic American images narrating her mother’s own anxieties, worries, cares. The subway car’s inertia unsteadies you. Epistolary horizons.

Natalia’s words, Chantal’s intonation: We only ask that you don’t forget us.

Dis-Moi (1980)

Jewish Grandmothers who survived the Shoah chastise Akerman for not eating. One grand-mère interviewee tells Akerman how the British put a stop to the Communists from ever forming a party in Palestine. Her parents, she said, renounced Zionism and tried to become Communist, but the British-colonial administration destroyed that option. Little pockets of resistant history, recorded in one of the first films to put an oral account of the Holocaust to screen. Natalia’s voice occasionally emerges, recounting how her mother and grandmother died at Auschwitz. Toward the end of My Mother Laughs, Akerman records her mother saying, at random: “My daughters have everything. Me, I have nothing but the camps.” “It was the first time she said that,” writes Akerman.3 No words left to describe this trauma.

Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman (1997) and Lettre de cinéaste (1985) and L’homme à la valise (1984)

Akerman asks, as Jews, “Our new country should be pondered,” imagined, critiqued: “Is our time our own?” Akerman urges us to notice how a “new country” is made and maintained. A nation state demarcates the borders that say from one group to another: Your home is our home. Where is home in Akerman’s oeuvre?

Akerman returns to us, “I live unnerved.”

I have to make narrative, lest I turn into salt. Being a writer is very embarrassing.

A shaggy dog. An apartment with a computer. Postmodern preoccupations. Akerman in the digital age.

Akerman pushes and pulls language, laying bare the fundamental comedy of living. In Family Business (1984), Aurore Clément, trying to announce the line “I never cheated on my husband,” declares with conviction and a heavy French accent: “I never shitted on my husband.” Akerman, suddenly in boy drag, queering the act of making movies. “One must get up to make cinema,” she says—an observation made in cheeky reference to Akerman’s past recumbent autobiographical short films. There is this urge to make movies that you hope your friends will like. Invoking intense physical comedy that records the affordances and particularities of sharehouse living, in L’homme à la valise, for instance. Akerman’s films are often so hermetic that when the outside does come in, the outside’s outsideness is quite a shock. The ending of Golden Eighties (1986) leaves us on the streets of Paris after spending the entire run-time inside the confines of an underground mall. A breath of fresh air! Out of the boudoir and into the street!

In My Mother Laughs, Akerman writes that:

I never thought of myself as an odd one or different in any way, not at all, I just had a way, a way that was mine and mine alone. A way that was maybe a bit peculiar but I liked that. I liked the fact that other people weren’t odd in the same way, but I felt that being odd suited me better than being popular. My oddness has a certain something, I thought. A style. A style that belonged to me. Then it became a habit and I no longer thought about my odd style, that was how I was and that was that. Different.4

Watching Akerman do comedy I am suddenly struck with a familiar pang. I see myself so acutely in the humour and in-jokes she deploys, the roundabouts and curves of her signature style and wit that feels so strange and different and attuned to a particular type of response to being queer, itinerant, an outsider, constantly moving, questioning.

Portrait d’une jeune fille de la fin des années 60 à Bruxelles (1994)

1968. The feeling of school as an institution which funnels kids, military-like, into roles.

And there were other girls who were odd ones too and that was how it was. And we loved each other and that was that. I was 18 in May 1968 and it seemed as though my style was becoming popular and that everything was going back to normal, if I dare use that word because I really don’t like the word normal. I prefer the word abnormal but only just because in the word abnormal you can still hear the word normal and that’s a word I really don’t want to hear.5

- Wanting to hurt someone else when kissing someone new.

- Crumbs in bed are too depressing.

- Keep a souvenir of your mother on you always.

No Home Movie (2015)

Barren branches battered by a wild wind that whips across the Naqab desert. The quotidian cadences that make up a matrilineal line, all those inheritances passed down from Grandmother to Mother. La Grand-mère to Mère. Babcia to Mamusia. Here, there, and elsewhere. An aside: when I first watched Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), all I could think about was my own grandmother. Translated across time: Jeanne’s meticulous gestures and habits and all that gendered work carefully attuned to the daily rhythms of care and (home)making (a living). I wanted to call Grandma after first watching, hoping to tell her that I saw bits of her on the silver screen. But she, like millions of others, died from a Coronavirus infection during the (endlessly unfolding and ongoing) pandemic. She is probably not even an official figure in the statistics of pandemic deaths due to a complicated mass of infections piled on top of one another, muddling a singular explanation, or ending.

Keep a piece of your grandmother with you always.

As a figure who looms large in Akerman’s work, who informs the structures of most of her films, the physical appearance of Natalia (Nelly) has the air of meeting a celebrity, someone felt through a parasociality almost as if I knew her myself, made all too apparent in watching No Home Movie, then reading My Mother Laughs soon after.

It always comes back to grandmothers.

The way she moves about the room, in audibly so much pain.

From Brussels to Oklahoma to occupied Palestinian land. An unsettled settler-colonial eye records long tracking shots of the Naqab desert; the nation-making project of dispossession and violent un-homing rendered aslant and explained away as somewhere else, là-bas (“down there”). There is no home in this home movie. The long stretch of absence and forced removal across generations; landscapes inhabited by memory, scarred by genocide(s), still ongoing.

There is no ceiling for the wind,

no home for the wind. Wind is the compass

of the stranger’s North.

He says: I am from there, I am from here,

but I am neither there nor here.6

Chantal tells Natalia to eat more, like a reversal of the grandmothers in Dis-Moi telling Chantal to eat more. Sleep and rest and waiting in time and tracing the outline of a life.

I liked making films but whenever I heard people talking about me using my full name I knew that they were talking about someone who hadn’t just left some kind of trace but someone who had made something more like a body of work. And I didn’t want to contradict them. No, certainly not. I didn’t want to tell them that they were just traces so I told them nothing at all.7

**********

Dylan Rowen is a writer and researcher based in Naarm. They are a PhD candidate in Screen and Cultural Studies at the University of Melbourne, where their research focuses on the representation of queens, fairies, and pansies in modernist literature and film.

- Chantal Akerman, My Mother Laughs. Translated by Daniella Shreir, with an Introduction by Eileen Myles and Afterword by Frances Morgan, Silver Press, 2019, p. 84. ↩︎

- Élisabeth Lebovici, ‘Her Cinema, Even.’ Senses of Cinema, Issue 77, 2015. https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2015/chantal-akerman/her-cinema/. ↩︎

- My Mother Laughs, p. 175. ↩︎

- Ibid, pp. 48-49. ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 49. ↩︎

- Mahmoud Darwish. ‘Edward Said: A Contrapuntal Reading.’ Translated by Mona Anis. Cultural Critique, University of Minnesota Press, 2007. ↩︎

- My Mother Laughs, p. 84. ↩︎