The Perfect Neighbor

George Floyd’s murder was recorded by a bystander, a Black high-school student named Darnella Frazier, using her phone. During the mass unrest that followed his death, one slogan pounced upon the idea of the public cameraperson as a means of justice against racist police violence: ‘Film The Police.’ Community members were encouraged to turn the architecture of surveillance around and watch the watchers, using social media as a means of breaking through censorship and media gatekeeping.

Conspicuously, there existed a recording of this event from an even closer perspective, though it was only released on a judge’s orders after five months of continuous protests. This was the body camera footage from Floyd’s cop murderers. The body camera, with its shaky, chest-level POV and distorted wide angles, has become quietly ubiquitous in media over the last decade, but its implications remain under-discussed. The documentary The Perfect Neighbor, released by Netflix late last year after its acquisition at the indie-prestige incubator Sundance Film Festival (and nominated this week for an Academy Award), is the first major film to be composed almost entirely of archival police bodycam footage. It investigates another racist murder, that of Black woman Ajike Owens by her white neighbour Susan Lorincz in 2023, after Owens attempted to confront Lorincz about the latter’s treatment of Owens’s children.

Lorincz’s shooting of Owens ignited protests against both the local police for letting the culprit walk free and Florida’s stand-your-ground law, which allows people to legally shoot and kill others in self-defence if they feel reasonably threatened, particularly in their own homes. Such laws have led to increased firearm homicides, particularly against Black people (Trayvon Martin is another example). Director Geeta Gandbhir, whose sister-in-law was friends with Owens, travelled to Florida to film the protests and their media aftermath. Her depiction of this moment is where the film is clearest in terms of its activist aims, allowing Owens’ family to speak for themselves and placing the focus on the structural issues behind the murder, rather than the murderer herself.

However, this formally traditional segment is only a small portion of the film, and the dominant atmosphere is not one of reasoned information or righteous anger but of tense horror. Lorincz herself is the perfect stand-in for a horror movie monster, a witchy adversary analogous to the suburbanite Aunt Gladys (Amy Madigan) in recent horror blockbuster Weapons (2025). She is shockingly racist and virulent towards the mostly Black residents of her neighbourhood, particularly the children, and so obviously crazed and unreasonable as to provoke widespread laughter in my film festival audience. Lorincz appears obsessed with the demarcations of her property lines, invoking their sacred power to threaten the kids playing around their boundaries, affirming her class difference alongside that of race. The horror genre has been entwined with real estate for centuries at the least, with children long warned not to trespass into the haunted house, lest they end up like Hansel and Gretel, or Goldilocks. Without much effort, the film presents Lorincz as a subverted take on Dracula—an outsider who moves to and disrupts a harmonious community through the dark, racialised magic of capital. In this case, of course, the threat was real.

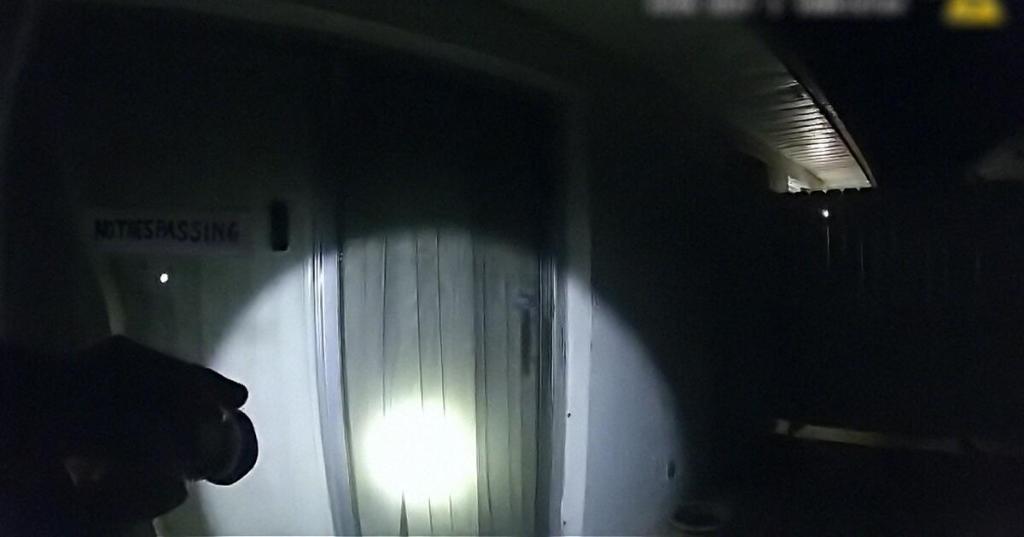

Through this lens, the film sits in a tradition of documentary-style found-footage horror that has adapted itself to the rapidly changing video formats of the times, from the TV special Ghostwatch (1992) to the home surveillance footage of the Paranormal Activity franchise. The final stretch of The Perfect Neighbor particularly resembles that of The Blair Witch Project (1999), with its shaky, nocturnal camera footage illuminated by torchlight and an uneasy sense of dread which, assisted by a crescendoing score, builds to a sustained note of hysterical horror-catharsis. The horrifying reveal of the climax summarises the promise of the genre—you knew what was coming, and here it is.

But in place of that famous Blair Witch shot of a possessed figure standing uncannily still, there is instead the blurred silhouette of Ajike Owens on the ground, a Black woman and caring mother, her body being quickly drained of life. Watching this, surrounded by a comfortable and mostly white audience in a plush Hoyts cinema, the thought kept occurring to me: why are we watching this? How did we gain access to this footage of a woman’s racist murder, strung together with the cheap thrills of genre entertainment? Moments later, the audience burst into laughter once again, as Lorincz admitted to the police her use of the N-word towards Owens’ children.

The horror of police

Applying the affect of supernatural horror to real-life cases is typical of true crime, a tawdry pseudo-genre with which Netflix has become near-synonymous. Though such a transposition can seem to merely exploit our curiosity in the vein of tabloid gossip, the relationship between crime and horror is deeply ideological, as explored in Travis Linnemann’s excellent 2022 book The Horror of Police. Drawing on a bevy of cultural theory, Linnemann asserts that horror arises from a confrontation with the abject truth of the world, that which we already know unconsciously but refuse to recognise, and theorises that the transgression of the criminal similarly exposes the violence of the liberal world-system, that of private property upheld by force. In Linnemann’s view, the political utility of ‘monstrosity’ is that “it invariably doubles back to reaffirm the orders transgressed.” Monsters like Dracula or Ted Bundy or Susan Lorincz can then be shown as aberrations outside of the social order and safely slain, thus reaffirming the system they arose from.

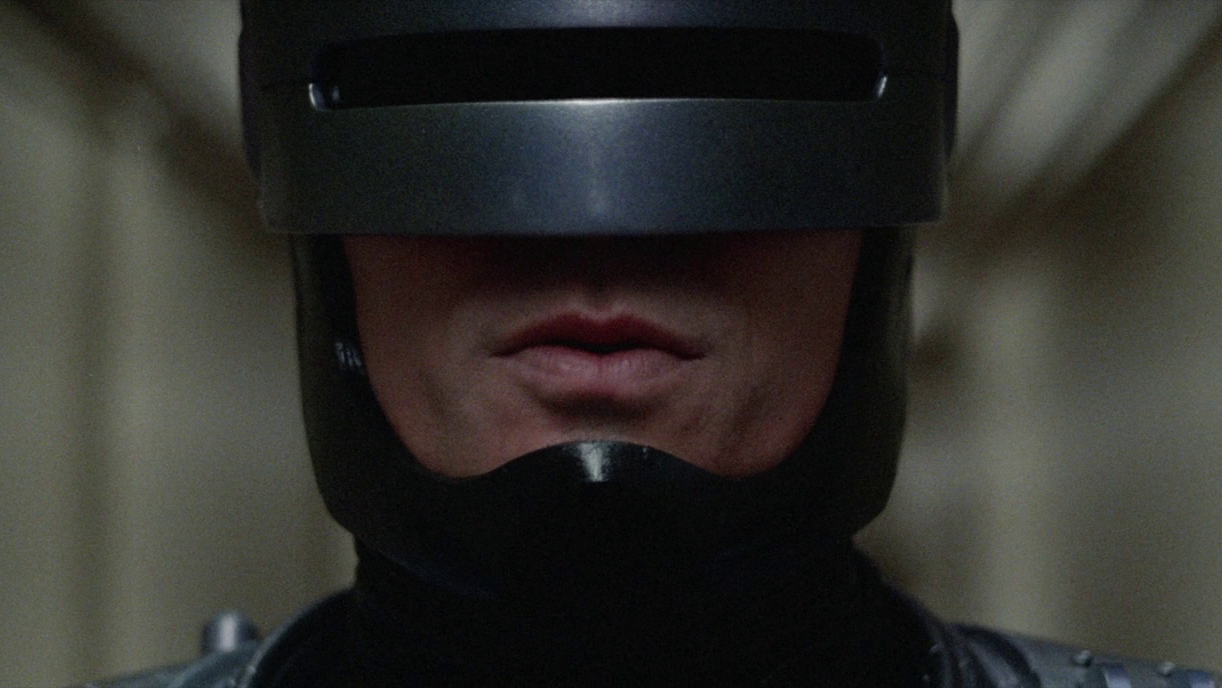

Police occupy a unique position in this theory, as they must vanquish the monstrously violent criminal threat using violence themselves. Linnemann shows police as both horrified and horrific, genuinely fearing the criminal’s violence while relishing in their own fearsome, uniformed brutality. The police exist in a state of perpetual emergency, at war with an apocalyptic threat hidden within the public, verging into monstrousness themselves for the assumed greater good. For the liberal bystander, the mirrored sunglasses or implacable helmet visor of the cop is itself a confrontation with the horrific Other, forcing the realisation that “policing is simply a project of superior violence and firepower… the biggest monster wins.” This is why so much effort must go into diverting attention towards the (racialised) idea of the criminal, lest the public realise that the most common serial killer is a cop. The simplest way to achieve this is simply to point people’s gaze in the right direction.

The emergence of body cameras

How did the radical abolitionist demands of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement morph into a consensus around a massive expansion of police surveillance? Anti-policing researcher Alec Karakatsanis studied this process in his essay for the Yale Journal of Law & Liberation, ‘The Body Camera: The Language of Our Dreams.’ The subtitle refers to a James Baldwin quote that encapsulates the problem of using surveillance as a tool of justice: “[T]he camera sees what you want it to see. The language of the camera is the language of our dreams.” The essay continues from Karakatsanis’s 2025 book Copaganda in detailing how an organised network of police agencies, NGOs, academics, politicians and media organisations managed to spin an obvious lie into a ‘progressive’ truth—the idea that being filmed by police somehow holds those same police accountable.

Karakatsanis paints the body camera as the ultimate Obamanite symbol of liberal police reform. Prior to 2014, the technology was marketed directly to police departments as an easy way to secure evidence and thus prosecutions for low-level crimes, ensuring a high turnover for the new era of mass incarceration. Body cameras would also serve as a form of protection—if video footage contradicted allegations made against an officer, they could instantly choose to release it, but if the footage bore out those allegations, it could be ignored for as long as possible. Here in Victoria, Australia, the anti-corruption commissioner warned against police being able to watch their own bodycam footage prior to making a statement after the practice tainted the evidence in a trial regarding a fatal police shooting. The police have thus far declined his recommendation. (Incredibly, bodycam footage was not even permitted as evidence in Victorian civil cases until 2022.)

It was only after the killing of Michael Brown and the subsequent Ferguson riots that pro-police ideologues in the US began selling bodycams as tools of ‘transparency’ and ‘accountability,’ buzzwords repeated to this day. Karakatsanis acknowledges a seed of truth in this narrative that makes the reform seductive, that “body cameras do, in rare circumstances, offer the public a way of documenting police violence.” There is, however, little-to-no evidence that cameras prevent that violence in the first place, and studies show that prosecutions involving bodycam footage target civilians over ten times more than police. Nevertheless, the transparency angle was laundered through academics tied to pro-police NGOs and uncritically parroted by the media, who could tie it to more traditional forms of ‘copaganda’ that emphasise the police as friendly or merely flawed. This collective push allowed both Republican and Democratic politicians to frame body cameras as a common-sense post-BLM reform. The existence of widely publicised bodycam footage has since become another excuse to continue police violence, in a cycle of endless expansion, regardless of who’s in charge.

The camera is a gun

Meanwhile, cameras were regarded as weapons amongst police themselves. One police chief quoted in The Body Camera validated the message of ‘Film the Police’: “Everybody on the street has a phone (video camera), we might as well protect ourselves.” Another high-ranking officer was caught lifting his body camera above a protest against the vigilante killing of Jordan Neely, to better capture the faces in the crowd. A US army manual is clear on such intimidation tactics: “To be effective, crowd members must see their presence being recorded… the cameraman should be in uniform.”

The idea of camera-as-weapon is made most obvious by the leading manufacturer of bodycams, Axon. The company was renamed from TASER in 2017, reflecting its shift in focus from its namesake electroshock weapons towards surveillance policing technology. The Tasers and cameras are now manufactured together. In the 2021 essay film/documentary All Light, Everywhere, which traces the technological development of cameras, director Theo Anthony and his team are taken on a tour of the open-plan Axon headquarters. While their tour guide proudly states that “there are no secrets here,” a literal ‘black box’ hovers over their heads, a room shrouded in tinted glass that acts as a panopticon of the office. The guide later demonstrates how the two-way glass can be turned on and off at will—“sometimes you don’t want people to see everything.”

All Light, Everywhere elucidates that moving image technology has always been developed in the context of the militarised capitalist system (an early example being the ‘photographic revolver’). Alphonse Bertillon, the 19th century French police officer who pioneered biometrics, was once quoted: “One can only see what one observes, and one observes only things which are already in the mind.” Bertillon had the mind of a cop, and his flawed, ideologically-driven evidence was used in 1894 to convict French army officer Alfred Dreyfus of false, antisemitic accusations.

Biometric images like Bertillon’s mugshots have become Axon’s most valuable product,. They wish to become a centralised data platform for police agencies, linking footage to cloud-based predictive algorithms and AI technologies. Other companies hawk their computing software to police agencies with slogans such as ‘CONVERT YOUR BWC DATA INTO AN ASSET.’ Body cameras are now one more node in the totalising framework of surveillance-based technocapitalism, and Axon’s market cap has ballooned from $11 billion in 2022 to $55 billion in 2025 alongside the rest of the AI financial bubble. Police violence is profitable; data is more so, and the pair are symbiotically intertwined.

Body cameras and screen entertainment capital

Another node of this data-driven matrix is Netflix itself, a trailblazer of the personalised algorithm model and the bridging link between Hollywood and Silicon Valley. In addition to Netflix’s own investments in generative AI, co-founder Reed Hastings sits on the board of AI startup Anthropic, which has partnered with US military and intelligence in advancing surveillance technology, and whose chat logs with AI Assistant Claude are given to police as evidence (Claude can even contact the police itself if it detects ‘immoral’ activity). Anthropic sells itself as advocating for safer, more ‘ethical’ AI—touting, for example, their refusal to partner with ICE. But given the integration of state security forces, especially in Trump’s USA, this is a hollow distinction, another example of the expansive logic of liberal reform. This is an industry profiting off every part of social murder and punishment bureaucracy, and tech startups like Netflix are one more leech on the bruise.

Screen entertainment capital has long been involved in policing, particularly in Los Angeles. When the LAPD turned to private donors in 2013 to fund their burgeoning body camera program, liberal moguls including Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg, and Casey Wasserman gave them a total of $1.2 million. In 2020, Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos was included on a list supplied by a consulting firm to the LAPD, which identified potential donors for the department’s chief to call directly. The local interest in surveillance is further evinced by the city of Beverly Hills, which operates over 2000 security cameras, making it “one of the most closely surveilled communities in the world.” There’s also the nearby neighbourhood of Cheviot Hills (home to many wealthy Hollywood alumni), in which a homeowners association recently raised over $200,000 for the LAPD to purchase high-tech cameras that scan suspicious license plates—but only for use within Cheviot Hills itself. The screen industry understands perfectly well that a camera is only as meaningful as where it’s pointed and who it’s pointed at.

In response to the BLM movement in 2020, Reed Hastings donated $1 million to the Centre for Policing Equity (CPE), an anti-racist NGO that specifically advocates for ‘data-driven interventions’ into law enforcement. CPE spokesperson and academic Hans Menos predictably criticises a lack of ‘transparency’ and ‘accountability’ regarding body camera practices, but not the cameras themselves. Menos formerly led Philadelphia’s Police Advisory Commission, an organisation that was similarly strengthened post-BLM and renamed the Citizens Police Oversight Commission. However, the organisation remained a ‘collaboration’ with the police, merely capable of passing on complaints for the department to investigate. Only 1.8% of these complaints led to a guilty finding and only 0.5% to a suspension, mostly between one and six days. At a certain point, the intentions of such organisations become meaningless; per Stafford Beer’s dictum, the purpose of a system is what it does. As Michel Foucault put it, “Prison ‘reform’ is virtually contemporary with the prison itself: it constitutes, as it were, its programme.”

Through the lens of liberal reform, every police officer becomes a RoboCop in waiting, a theoretically perfect cyborg soldier—if only when subjected to the right concoction of ideological programming and technological augmentation. In The Horror of Police, Linnemann points out that ‘RoboCop’ is a common nickname among police, given fondly to particularly brutal colleagues such as Detroit’s own William Melendez, despite the pointedly satirical tone of Paul Verhoeven’s 1987 film. Police officers are proud of their robotic inhumanity, obediently following procedures to dish out violence while actively creating the law through their actions, and shaping their minds and bodies using the technology of the day, from steroids to GPS tracking. The expulsion of ‘bad’ or ‘crooked’ cops by the system, as encouraged by the body camera’s focus on publicising occasional illegitimate acts, is then like the autotrophic machine of the police state repairing its code, its waiting violence haunting it, spirit-like, as Walter Benjamin saw it: “formless, like its nowhere tangible, all-pervasive, ghostly presence in the life of civilized states.”

The body camera image

If we take seriously Roger Ebert’s claim that cinema is an ‘empathy machine,’ then the point-of-view shots in RoboCop from inside the title character’s helmet seems a powerful means of associating ourselves with his perspective, that of a violent crusader against corruption. What then to make of The Perfect Neighbor, a film that inhabits this POV for almost its entire runtime? We never actually see any of the confrontations between Lorincz and the rest of the neighbourhood—only their aftermath, experienced through our police avatars. Some scenes of the police interacting with local children play out similarly to propagandistic news stories of officers joining pick-up basketball games or supporting a child’s lemonade stand. The film even includes candid conversations between officers in their cars that state their support for the kids playing, emphasising their bemusement at Lorincz’s bizarre behaviour.

It is worth considering the aesthetic and formal qualities of the body camera image, given the film’s reliance on it. With its trembling, ungainly motion; starkly digital look; and distorted low and wide angle, the image produced is both unsettled and unsettling. Within its frame, movements are made more severe; silhouettes seem taller; the mood tenser; and the mise-en-scène more menacing to the viewer conditioned by news items to expect an eruption of violence. The body camera image perfectly replicates and enhances the ideology of ‘the horror of police’ for the viewer, a perspective that twitches at shadows while remaining entirely assured of its righteous power.

The Perfect Neighbor’s upsettingly cathartic climax, with its rattling frame and overwhelming score, didn’t feel too dissimilar in the Hoyts cinema than the theatre chain’s thrill-ride ‘DBOX’ experience, which tilts and rattles each chair in sync with a given film’s action beats. This gimmick is part of a broader push towards immersive experiences within the entertainment industry, from VR headsets to Vincent van Gogh ‘exhibitions’ that feature gigantic walk-through projections in place of paintings. To my mind it’s a cynically fascist trend: a willing, semi-ironically brainless submission to screen technology. Within cinema this is best-represented by IMAX, which boasts that its king-sized screen and “powerful sound and vibrations envelop our audience to create a fully immersive movie experience.” The size matters less than how it’s used: as a marketing commodity. Despite the IMAX theatres themselves still exhibiting cinema as an art form, the cult of cinephiles that fetishise them are probably closer than they think to patrons of the AI-powered 4D Wizard of Oz Experience at Las Vegas’s monstrously large ‘Sphere’.

The immersive body camera image as deployed by The Perfect Neighbor is then perfectly positioned as ‘Police: The Experience’ (which, given the implicit role of the police, is also ‘Racist Murder: The Experience’). This obsession with an immersive realism can be traced back to voyeuristic filmmaking techniques as popularised by Alfred Hitchcock, and now suffuses “ultra-realistic” first-person shooter games. It is also part-and-parcel with the body camera’s purpose—to “see what [the officers] saw,” as the Axon guide in All Light, Everywhere expresses.

A brief history of verité copaganda

Cinéma verité (aka ‘truthful cinema’) was coined in the 1960s to describe an emerging mode of documentary filmmaking that directly acknowledged the presence of the camera. Practitioners were concerned with ideas of reality and whether a ‘true’ observational cinema was even possible. Of course, this aesthetic mode was quickly subsumed by commercial fiction cinema looking for a pseudo-naturalistic bite, inadvertently proving that any idea of a hard truth in cinema is a fantasy. There’s always someone behind the camera and in the editing room and in the distributor’s office, choosing what we see and how we see it. Bodycam footage could then be termed ‘vérité copaganda,’ given both its claim to directly observed reality and the cynical forces at work behind it. But this did not begin with body cameras. In the same way print media has been gradually and overwhelmingly replaced by video, copaganda has always adapted and integrated itself into the dominant formats of the day.

The television program Cops (1989-) follows police as they invade the homes of mostly poor, mostly Black or Latino people and violently arrest them for petty crimes, often related to drugs, assault or sex work. Created by a former military intelligence officer, Cops premiered at the dawn of modern reality TV and the 24-hour news cycle, and collaborates with police departments to embed its film crew in police raids and thus engineer a vérité documentary style. This is remarkably similar to the practice of ‘embedded journalism’ utilised by the US since the Iraq War, in which friendly war correspondents are placed in military units and their output strictly controlled for propaganda purposes (more recently, such controlling tactics have been seen in Ukraine and Gaza).

The camera crew themselves are also far from neutral observers, not just encroaching on the victims’ privacy and dignity through their presence, but sometimes engaging in police work themselves by helping to catch or physically detain fleeing suspects. One long-time crew member was even shot and killed by police gunfire during a robbery—his sacrifice was honoured with an hour-long ‘best of’ episode. Such events blur the line between cop and cameraman, just as the program’s POV immersion encourages the viewer to identify with the police and relish in their violence. A 2004 study indicated that episodes were selectively edited to only show police actions based on ‘hunches’ that were successful, which served to promote practices of racial profiling. Though viewers may not consider Cops to be as veritable a source of information as the nightly news, both promote a Hobbesian view of the outside world as inherently barbaric and chaotic, requiring constant intervention by the forces of liberal order to be tamed. The news accomplishes this rationally and sources like Cops experientially, though over time the margins between these two streams have blurred.

You can now watch Cops on YouTube alongside channels like PoliceActivity, one of many new online platforms that showcases vérité copaganda. The channel has racked up over three billion views on its videos, including those of fatal shootings (the top comment on one of these: “Once you start watching these you can’t stop..”). Some videos synthesise this newer format and more traditional feel-good stories, such as one titled ‘Georgia Officer Saves Choking Baby’—the officer is white, the baby is Black, and the camera is a dashcam pointed outwards. Despite these videos’ obvious intention as cheap entertainment, PoliceActivity’s disclaimer states that it exists for educational purposes, “to provide an unfiltered and unbiased look into law enforcement.” But given the overwhelmingly pro-police ratio of such videos released to the public, any footage to the contrary can be interpreted merely as unfortunate incidents, the work of singular ‘bad cops’ or ‘bad departments’ (though Alec Karakatsanis notes that most people across the US tend to believe their city’s cops are particularly ‘bad’).

Since that channel’s inception, TikTok and its attendant social media innovations have created the era of the endless, algorithmic scroll, and copaganda has gladly come along for the ride. The body camera image has even found a successful outlet in generative AI videos. A recent YouTube exposé titled ‘Fake Bodycams Are Out Of Control’ looked into how channels propagate these fake videos by mixing them in alongside the real thing. Such videos can be as outrageous as required to get clicks, with a common trope being that of the crazed, out-of-control ‘Karen’—a woman like Susan Lorincz, now infinitely replicable. The generic similarities of the propagated body camera image and the clichéd sameness of vérité copaganda (drawing from the rigid pro-police ideology it springs from) means that the form is ripe for iterative, algorithmic generation. Michael Brown, George Floyd, and every other victim of police violence have thus been perversely made the catalysts to feed a hungry and ever-expanding trove of data, from which a factory line will endlessly assemble and broadcast shambolic simulacra of their deaths as mechanistic commodities, animatronic effigies on a digital bonfire.

‘All you need for a movie is a girl and a gun.’

According to her testimony, Lorincz shot Owens because she felt scared, after Owens briefly banged on her front door. This was despite Owens being unarmed and non-violent, and Lorincz having a gun. It’s a ludicrous statement, but one that I fully believe. Lorincz’s racism is part of the same substance that animates the horror of police—a fear of the Other, alongside a projection of fear towards them. Owens was shot through the door, a literal outsider. Though Lorincz was undoubtedly a fully willing and active participant in the murder, she was nonetheless programmed to kill Owens through a lifetime of video copaganda. Italian philosopher Maurizio Lazzarato posited in 1996 that video had become pivotal to our ‘machinic enslavement’ to capitalism, due to its ability to directly embed itself into the rhythms of cognition and thus restructure our subjectivity and experience of temporal events. In pulling the trigger, Lorincz was autonomically expressing the affective power of copaganda’s media-driven ideology. The film made about her dutifully does the same.

Police power haunts—and even directs—The Perfect Neighbor from behind the body cameras, possessing both those recorded in the film and those watching it. Each community member interviewed on the street and each police officer is well-aware of the threat behind these cameras and performs accordingly, adjusting their ‘real self’ to match the scene’s requirements. We never see the kids playing—when the cops arrive, everyone theatrically lines up in the street, waiting to be directed through the prescribed interaction with police. When an officer occasionally appears on-screen, filmed through the camera of a colleague, the impact on the audience is jarring, like suddenly seeing oneself within the frame.

In Copaganda and The Body Camera, Karakatsanis focuses his critiques on well-regarded liberal organisations such as The New York Times, who can sell copagandistic narratives to the broader public far more deftly and effectively than blatantly right-wing, pro-police outlets.The Perfect Neighbor, which arrives with an inbuilt, legitimately progressive message (opposition to racist stand-your-ground laws), the backing of the victim’s family, and a relatively ‘neutral’ outlet in Netflix, is a perfect vehicle to legitimise the police and their violence and surveillance, regardless of intent. Netflix’s acquisition of the project is then comparable to Reed Hasting’s post-BLM donation to the CPE, a tactically considered method of signalling anti-racist bona fides to a targeted consumer group without upsetting the delicate balance of the racist pro-police consensus. In a country where the release of a single bodycam video has often required years of litigation, it should raise an eyebrow that this film had access to almost two years’ worth of footage.

Despite The Perfect Neighbor’s critique of the police’s shocking laxness in arresting Lorincz, she is eventually arrested and safely convicted, with more cameras bearing witness at her trial. The existence of the film-as-document is a vindication of the system that produced it. Sure, it has its faults, but it can still be prodded into doing the right thing—thank God we have this footage to help change things further! The point is the witnessing and the broadcasting, the constant churn of new data, further proof that reform must be necessary. What goes unsaid is that the presence of these cameras did nothing to save Ajike Owens and will do nothing to help future victims. The risk posed by Lorincz, as well as the evidence against her, was clear as day from the start—it was present in the eyes and ears of her neighbours, in the community she saw herself apart from.

It’s not that there can’t be worthwhile art made with these images, or within these systems of power—all radical and revolutionary statements emerge from oppressive contexts, using whatever tools and texts are at hand. But no progress can be made if we are not aware of what we are watching. Cameras are weapons, so film the police, and don’t let them film you. If the camera is the language of our dreams, then we need a wake-up call.

**********

Fred Pryce is a writer currently living in Naarm/Melbourne. As a critic, his writing has been published in Overland, and he participated in the Critics Campus program at the 2025 Melbourne International Film Festival. He is also a playwright and works as a public servant.