Pascal Bonitzer’s The Stolen Painting (Le tableau volé) is based on a true story, but it is a tale of lies and deception, of misdirection and bad faith. One thing is certain, however, in this fictional narrative: the identity of the rediscovered canvas at its centre. “The question of fakes is a big part of [the art] world,” Bonitzer says, “but I didn’t want to go into it.” He found more rewarding tensions and ambiguities elsewhere.

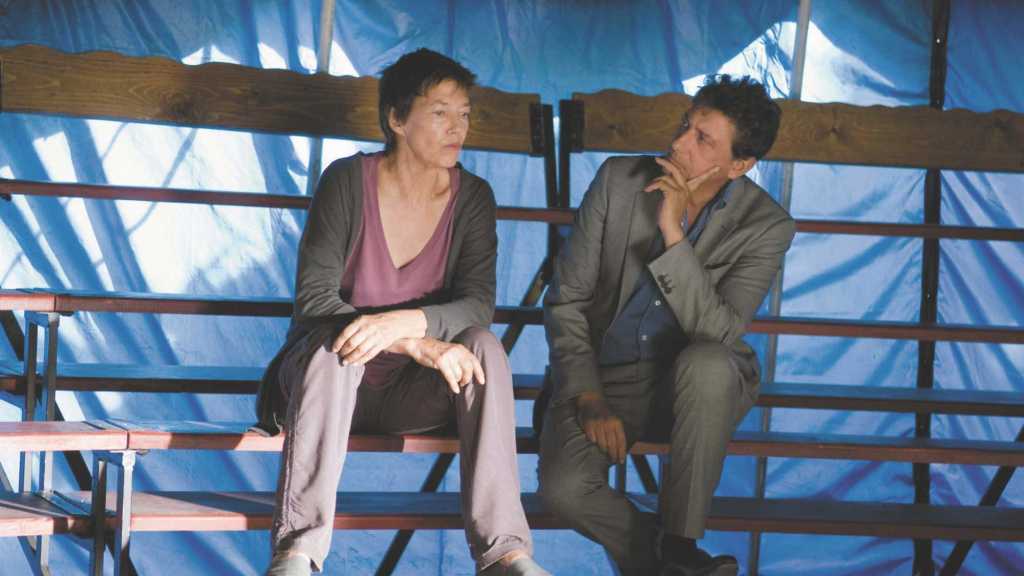

We talk about the opening scene of the film, in which he creates a context for the milieu he is exploring and introduces two characters whose shifting relationship is a significant element in what follows. Art expert and auctioneer André (Alex Lutz) and his intern, Aurore (Louise Chevillotte), are visiting the home of a wealthy elderly woman (Marisa Borini) to discuss the impending sale of a painting she owns.

This woman, imperious and demanding as she sets out her terms of sale and her reasons for disposing of the work, also reveals herself to be malicious and racist. Alex takes it in his stride, serenely acquiescing to it all. The lesson, he tells his intern as they make their way back to the office, is that “You have to stop at nothing for a sale.”

Bonitzer was inspired to write the scene, he says, by something a modern art expert at an auction house told him. “He said he was nicknamed Triple F: that stands for ‘Filou, Fayot, Faux cul.’” The closest English equivalents are, more or less, Rogue, Bootlicker, Hypocrite. The job, he told Bonitzer, was to please potential customers, to persuade them to sell with his organisation. Whatever they said, however unacceptable it might be, you simply went along with it.

The visit to the seller of the painting referred to in the film’s title is a very different matter. Alex travels to Mulhouse, in Alsace, to see what he assumes will be a copy or a fake. But when he and a fellow expert set eyes on the work, they immediately burst out laughing. It’s a reaction of disbelief. They are looking at something they never thought they would see, something they assumed had been lost forever.

The authenticity of the painting is not in doubt, but many other things are, including ownership, value, business considerations, and moral and ethical questions. Several of the figures involved in the process have their own priorities, interests, and secrets. And Aurore, a novice in the art world, is a veteran when it comes to deception.

Bonitzer drew his inspiration from an extraordinary turn of events that took place in 2005, when a major work by Expressionist artist Egon Schiele, Wilted Sunflowers (Autumn Sun II), was found in France as the property of an anonymous Frenchman who had no notion of its provenance. The work, which was painted in 1914, had last been seen in public in 1937, at an exhibition at the Jeu de Paume in Paris. It had then belonged to an Austrian collector, Karl Grünwald, who was a friend of the artist and had sat for a portrait by him. In 1938, Grünwald, who was Jewish, fled Vienna for Paris, taking 50 paintings with him, hoping to save them. They were looted from storage, however, and later auctioned off. Grünwald survived but his wife and one of his four children died in a concentration camp. He went to the United States and spent the rest of his life trying to recover his stolen paintings; after his death in 1964, one of his sons continued the quest.

In The Stolen Painting, Bonitzer imagines the Schiele hanging on the wall of a house belonging to a young factory worker, Martin (Arcadi Radeff), who has no idea of its value or history. “I love this character, and I love to work with the actor, Arcadi, who was so good, so sensitive and clever in this role.” At the same time, he says, it was important not to turn Martin into an exemplary figure. “I wanted him natural, not edifying.”

There was something about the Schiele itself that also intrigued Bonitzer, that made it a kind of open text—a version, perhaps, of van Gogh’s Sunflowers, but with very different resonances. “It’s not one of his usual works. He’s known for nudes, for erotic, tormented work, but happily, this painting is somewhat neutral; you can project a lot onto it.”

Bonitzer, born in 1946, is a critic turned screenwriter turned director. For many years, he wrote theory and criticism for the influential Cahiers du Cinéma. Later, between 1986 and 1994, he was head of the script department at the Paris film school La Fémis. He has published collections of his criticism and co-authored a book on screenwriting.

His first screenwriting credit was on Moi, Pierre Rivière… (I, Pierre Rivière…) a remarkable 1976 film based on the 19th-century memoir of a convicted murderer from a small rural French town. The case had been the subject of a study by historian and philosopher Michel Foucault and his students. The film was based on the memoir and shot with non-actors from the region in which the events took place.

His credit on Moi, Pierre Rivière… is a little misleading, Bonitzer says. “I wouldn’t want anyone to think that I worked on the screenplay itself. I did a certain amount of preparatory work, but the film was principally written by René Allio and Jean Jourdheuil. But it was important for me—it was the first rung on the ladder, it was my entrée to the career of screenwriter.” Working for Cahiers, he says, played a part in this too. “It was thanks to my work as a critic that I was able to meet people like André Téchiné, Benoît Jacquot, Jacques Rivette, or René Allio. That allowed me to cross over to the other side, as it were.”

The next stage involved a long period of collaboration. He made more than ten films with Rivette; he worked on several occasions with Téchiné; and he has also written with Raúl Ruiz, Chantal Akerman, Raoul Peck, and Barbet Schroeder, among others.

Working with Téchiné and Rivette was a study in contrasts, he says. “Téchiné was very demanding in terms of the actual writing. He was a great screenwriter as well as a great director and I learned a lot from him about the construction of story.” Their first collaboration, The Brontë Sisters (Les soeurs Brontë, 1979), was his first proper credit, he says. He began a long collaboration with Rivette in the early 1980s, with what was to become Love on the Ground (L’amour par terre, 1984), and continued to be involved in every movie the director made, up until his last, Around a Small Mountain (36 vues du Pic Saint Loup) in 2009.

It was a screenwriting experience like no other, “singular and very formative, notably for dialogue, because [Rivette] asked me to write scenes during the shoot. Sometimes solo, sometimes with others, I wrote while the film was being made, in direct contact with the actors and crew, close to the shoot itself. It’s very rare; it hardly ever happens like that. And it was a great liberty, and a great pleasure.”

When Bonitzer was interviewed for Libération after the 2016 death of Rivette, he recalled how they started out, with Love on the Ground, by simply meeting at a café and talking about all kinds of things, such as books they had read or films they had seen. On set, he added, “He was a very intuitive filmmaker who manipulated people a lot, with this method of quasi-improvisation and changing the script and dialogue on the spot […] He put everyone in a state of tension and danger, but it always remained enjoyable because he was charm itself.”

There was only one exception to this on-set work, he says, “and that was for a practical reason. With The Duchess of Langeais (Ne touchez pas la hache) I was shooting my own film at the same time, so I wasn’t able to be on his set. We wrote the basic screenplay beforehand.”

It wasn’t until 1996, at the age of 50, that he directed his first feature. He says that it happened in a way that is characteristic for him. “I always approach things backwards. And in this case, I never felt I was ready until the moment someone asked me to. A producer said to me—he was a young producer who had made very few films—‘If you have an idea and you write something and I like it, we’ll do it.’ So I wrote something, he liked it, and that was my first feature and also the first film I wrote on my own, without a collaborator.” Encore, the story of an academic’s midlife crisis, won the Prix Jean Vigo, a prestigious prize awarded to a first feature, and launched his career as a writer-director.

He has continued to make his own films, and to work on screenplays for everyone from Anne Fontaine to Paul Verhoeven to Catherine Breillat. Writing in 2021, Daniel Fairfax notes that Bonitzer’s films “appear on the surface to generally conform to conventions of narrative realism that he and his Cahiers colleagues had so extensively condemned in the post-1968 period, but there are features in his filmmaking that subtly depart from dominant filmmaking practice: surrealist touches, uncanny moments and a generally dreamlike quality to the intricate twists and turns of his storylines.”1

His next feature, currently in post-production, Maigret and the Dead Lover (Maigret et le mort amoureux) is due for release in 2026. Denis Podalydès plays the celebrated inspector Jules Maigret of Georges Simenon’s fiction, a character played by more than 30 actors over the course of decades. “It was by chance,” Bonitzer says, of the reasons for making this movie. “I was approached about it and I just happened to have read the book a fortnight earlier. It was a sign, so I thought: it will be my next film.”

The Stolen Painting is now playing in Australian cinemas courtesy of Palace Films.

**********

Philippa Hawker is a film and arts writer. She is working on a book about Jean-Pierre Léaud.

Philippa Hawker travelled to Paris with the assistance of Unifrance.

Header portrait courtesy of Renaud Monfourny.

- See ‘Partial Vision: The Theory and Filmmaking of Pascal Bonitzer’ in The Red Years of Cahiers du Cinéma (1968-1973). ↩︎