This evening, Saturday 31st of May, the inaugural Brunswick Underground Film Festival will screen a string of lost pornographic films made in 1970s Sydney by groundbreaking filmmakers George and Charis Schwarz. Unearthed by Leon O’Regan of Ex Film, the restoration of these rare films is a corrective action on the Australian canon. While O’Regan doesn’t expect any wild orgies to break out at any of the sessions, this is an unmissable opportunity to witness the Schwarz’s forbidden avant-garde world on the cinema screen.

Note: the following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Charles Carrall: These films were originally intended to arouse something in an audience. I sense also that George and Charis aroused one another in their creative lives. What did these films arouse in you?

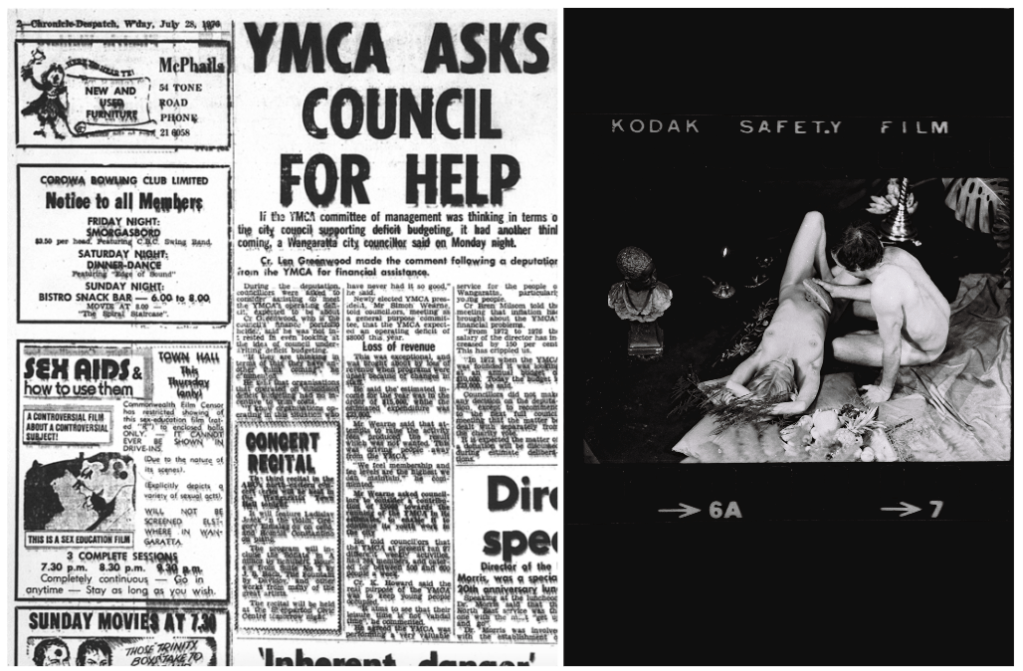

Leon O’Regan: Disbelief. At the time when I discovered these films in 2013, there was virtually nothing written about them but for a very brief reference in Madam Lash’s autobiography and an old ad on Dean Brandum’s fantastic (now gone) Melbourne cinema history website, Technicolour Yawn. I’d stumbled across Sex Aids and How to Use Them [1974] by accident while researching another film I was working on restoring at the time—there was an ad in a rural newspaper which exclaimed “SEX AIDS,” “one night only,” and “this is a sex education film.” There was nothing on IMDb and at that point it was as if this film had perhaps never existed or was a retitled production from overseas.

I visited the NFSA [National Film and Sound Archive of Australia] to view some very ropey low resolution video files of Charis and George’s films and could not believe what I was seeing. Here were Australia’s first theatrical entries into the canon of 70s adult cinema—a lauded and heavily mined terrain overseas, but here in their home country these films weren’t even a footnote; they were virtually forgotten outside of the surviving people who had seen them in cinemas. They struck me as so wildly different to what was concurrent in other parts of the world and for various reasons. The political climate of Australia is a major factor, but also the fact that Charis and George were artists and did not come out of a film industry establishment—they were countercultural bohemians living in an era of Kings Cross that was about to undergo massive cultural change. I wanted to know more and found George and Charis’ home phone number in the White Pages. George answered the phone and invited me to visit their home and talk about the films. I met Craig Judd that day who was writing a book on them (Powerful Paradise, published in 2021—it’s incredible and has a whole chapter on the films). We compared notes that day and both agreed that we had discovered unique and largely unheralded artists that the world needed to know about.

CC: Sex Aids was the first film of its kind to be passed by Australian censors. Since then, there has been an advent in education around sex. But I wonder if the erotic dimension, that George and Charis articulate in their filmic lovemaking, has been lost. Did you feel like you found something that had been lost, not just literally, but also culturally?

LO: To some degree yes, perhaps more so in the black-and-white art films that Charis and George made. They’re erotic but focus on atmosphere and moods, utilising landscapes and settings that are evocative of something ethereal—[a kind of] urban Australian gothic.

There have been artists working with sex and sexually explicit imagery for many years, but much of it is abstract or conceptual. Nobody is really making sexually explicit films disguised as documentaries anymore, probably because there is no commercial market for that style of film and it’s such a strange bygone concept that it really doesn’t make sense given today’s standards. Sex Aids was submitted to the censors with written commendations from doctors and psychologists in order to convince the censorship board that they were okay for public viewing, and I doubt that any film or work of art would require that today. I might be wrong, but it feels like the scope of what is being explored today is so broad and our philosophy, acceptance, and understanding have evolved. In other ways… maybe not so much. Perhaps in some ways we’re even more conservative than we were in the 70s and those sparks of ideas and inspiration were snuffed out or hidden from view until a new generation picked up the conversation again. I love that so much with digging into the vast universe of our cultural history. There is still so much to be discovered that was overlooked or neglected because people were looking the other way—the tiny glittering jewels that are sitting there waiting for us to unearth, to help us make sense of ourselves and our current day, our myriad of problems.

CC: In Sex Aids the narrator warns of overexposure, to toys, but also to pornography. Do you think we’ve reached a state of impotence and overexposure today? How can we, as the film puts it, “maintain an adult sense of balance”?

LO: Good question! I’m not too sure. I think that’s very complicated. I didn’t grow up with freely available pornography, it was harder to find back then and you had to seek it out. I really don’t know what effect having ‘porn on tap’ has on our society at large as it wasn’t my lived experience, but I’m sure it’s negative for some people, just like anything else which stimulates the brain. I do think that people can forget that what they’re watching are actual human beings with lives that extend beyond the screen and [that] the vast majority of those people are only making that sort of content as a way to make money. People still use assumed names when they make those sorts of videos, so it’s evident that there are still some aspects that we find shameful or potentially damaging.

Respect and love are still traits that humans struggle with. We’ve conflated physical pleasure with commerce and I hate that. And as sex-positive as some social circles are, it’s still not something that’s widely accepted or agreed upon—‘eroticism’ and ‘balance’ are subjective, and community standards are constantly changing. The sun still rises every day, and the bastards are still running the world, so I think that porn in everyone’s pocket is really a low-scale problem for humanity.

CC: These films and the fucking in them are imbued with a sense of something quite ancient, where “variations practiced for thousands and thousands of years” are performed in a “creative kind of way” by everyday people. What is the historical significance of these documents for you?

LO: I’m glad you picked up on that. You don’t really see this sort of thing anymore. They’re a product of a totally different society that is quite difficult to conceptualise unless you were actually there. As far as Charis and George’s hardcore works go, these can only be observed as historical works. They’re barely recognisable as pornography despite the graphic content. The Dream (1970) is art meets erotica and the fact that it is the earliest Australian produced explicit film intended for theatres certainly makes it a historical piece. With Sex Aids and Well, My Dear! [1975] Charis and George had to work out ways to present explicit sex as ‘educational.’ They got away with it with the former but Well, My Dear! was completed and never screened after it was refused classification. It’s baffling now as it’s quaint in comparison to what we’ve seen in subsequent decades, but for its time it was a total shutdown from the authorities.

Charis admits that perhaps she and George pushed things a little too far with the content of that film and it deviated from the documentary framework of Sex Aids. In the US, these types of documentary films were known as ‘white coaters’—in the 50s and 60s there were a number of sexploitation films disguised as documentaries, which would show nudity and in some cases unsimulated sex acts. A live host would present the film posing as a doctor and often hand out sex education pamphlets. These films were extremely successful and simultaneously pushed the educational and sensational shock elements to draw a diverse crowd. The history of sex education films in Australia goes back to the silent era but in the years before Sex Aids was released, there were two Swedish films which were massively popular in Australia—Language of Love (1969) and its sequel, More About the Language of Love (1970). Both of these were dubbed into English, featured unsimulated sexual activity and played at cinemas and drive-ins all around the country for years, making the distributors a lot of money. The fact that these were passed by the censors meant that there was an opening for some brave locals to do the same, and thus Charis and George stepped up.

[Charis and George] were paid a flat fee from the producers, which set up their darkroom for their subsequent art and photography practice for which they are more widely known. Since they were making films just a little too early to catch the boom in the Australian film industry and the fact that they were both free-thinking, anti-establishment artists, it’s really no surprise that the funding bodies didn’t know what to make of them and their ideas. This is strangely in contrast to the massive success of Sex Aids, which made a ton of money for the producers and played in cinemas until around 1980.

CC: In their film work, Charis and George captured the tumescence of Kings Cross at the time and, particularly in Stage (1972), we get the feeling of a scene that no longer exists anymore. The porn cinema also is an abandoned concept. With this in mind, where do you think these restorations belong, how are they to be enjoyed? And by enjoyed, I mean to the fullest.

LO: It’s interesting to me that people used to have to go to a cinema to watch this sort of stuff unless you could afford a projector and your own personal 8mm or 16mm collection of whatever was being smuggled into the country. Most of Charis and George’s films are R-rated, so they’re legal but outside of the Northern Territory or the ACT it’s still illegal to sell X-rated material. That’s so archaic to me, that despite it being freely available on the internet, Australian laws are decades behind: an anachronism that is a perfect summary of Australia. Charis and George’s films are erotic, but their sexually explicit works really don’t operate in the same way as contemporary pornography. I don’t expect wild orgies to break out at any of the sessions, though it’s great to screen these films in a theatre. For most audiences this will be the first time they have watched something like this with a room full of people.

I’m working on releasing the entire restored and collected works as a Blu-ray with an extensive booklet. There’s so much more to the story of these films and the circumstances in which they were made. Charis and George had a number of unrealised film projects, one of which, The Bike Girls, was about a lesbian motorcycle gang. This was years before [the Australian Sandy Harbutt film about an avenging outlaw biker gang] Stone (1974) and if they had been able to secure funding and completed the project, Charis and George would be global cult figures. Then there are the stories of John Sangster, the legendary composer who scored several of these films; Pete Crofts, the most well-known doorman and Kings Cross club spruiker known around the Cross as ‘Half Mo’; the notorious Madam Lash; Colin McAuley from [bands] The Black Diamonds and Tymepiece who appears in Well, My Dear!; Mark Lewis who appears in Stage and learned his filmmaking craft from George and went on to produce countless TV shows, feature films and the widely seen documentary Cane Toads (1988). All these vibrant characters were in the orbit of Charis and George and against the setting of Kings Cross in the 70s. It’s just such a wild ride. I really enjoy creating a reference document that people can add to their library, not just something for me to sell but something that creates perspective. I think that’s an interesting element to virtually anything once enough time has lapsed, perspectives on moments in time shift and develop a historical component that was not initially intended to be there.

I’m also hoping that the artistry of these films will be appreciated. George had a great eye for composition and atmosphere, which is particularly evident in the black-and-white films. I think they also say a lot about Australian society. Sex Aids was the first movie to be banned in Queensland under their revised censorship laws in 1974. Well, My Dear! was locked away and forgotten for decades, as the censors thought it went too far. The Dream was frequently confiscated by vice squad detectives and was all but lost until Charis found the remaining footage in a matchbox in her home. Sailor Doll features a homophobic assault which was a fear that most gay Australians lived with in 1971, regardless of whether they’d moved to inner Sydney to be with their community or remained closeted in the suburbs. These films are a time capsule of that era and commentary on Australian society. They’re a goldmine of ideas from a lost zeitgeist that could have vanished from our collective memory had I not reached out and called George on his home phone. I’ll never forget him and Charis welcoming me so late into their lives, allowing me to become a part of their story and carry their filmic legacy into the world.

A collection of the Lost Sex Films of Kings Cross, including The Dream, Sex Aids and How to Use Them, Well, My Dear!, and Stage will screen in two sessions on Saturday the 31th of May, as part of Brunswick Underground Film Festival. Find session details here.

**********

Charles Carrall is a writer and critic from Sydney, Australia. He makes up one half of the podcast Vanity Project.