Farsi biin ta ba-biini naqsh’ha e rang rang

Ba-guzar az majmua e Urdu ki be-rang e man’ast

See Farsi to see the impression of colours

Skip the Urdu collection that is my faded colour1

This verse by Mirza Asadullah Khan ‘Ghalib’ (1797–1869), one of the most widely quoted, sung, and mythologised poets of the Indian subcontinent, can be read as a moment of self-confession—a reflection on his own literary output. Ghalib was a master of the lyrical poetic form called the ‘ghazal.’ While he composed verses in both Persian and Urdu languages, his literary output in Persian was almost four times as much as in Urdu. Yet, consider the cruel hand of fate. Despite this prolific output in Persian, he is mostly remembered today for his body of work in Urdu. He had a strong desire for his his work in Persian to be taken seriously in literary circles, to the extent that he began his only published Urdu diiwaan (poetry collection) with a verse that references what is believed to be an ancient Iranian custom of a plaintiff dressing up in a paper garment to protest injustice.

Naqsh faryaadii hai kis kii shokhii-e tahriir kaa

Kaaghazii hai pairahan har paikar-e tasviir kaa

To whom are the markings complaining of the trickery of the writing destiny?

Made of paper is the clothing in the appearance of every persona2

This example by Ghalib is noteworthy when approaching Canadian writer-director Matthew Rankin’s second feature Universal Language. Ghalib’s life and work demonstrate how improbable connections can form between people, cultures, and communities despite seemingly vast geographical distances. Ghalib is one of many poets from the Indian subcontinent who was foundational in creating new linguistic idioms, expressions, and proverbs that many speakers from South Asia employ in their everyday speech. Hindustani, the lingua franca across much of northern India, Pakistan, and surrounding regions, is an amalgam of Persian, Urdu, Arabic, Sanskrit, and other linguistic influences, such that a single spoken sentence contains etymological roots spanning multiple geographical borders. One of the foremost delights of engaging with Ghalib and other classical Hindustani poets is this realisation of how fluid and untethered language can be when viewed through a less rigid, prescriptive lens.

Rankin is more than comfortable traversing this in-between space. Universal Language, co-written with Ila Firouzabadi and Pirouz Nemati, imagines an alternate reality where most of the characters in Winnipeg converse in Farsi with occasional French sprinkled throughout. Yet you wouldn’t call it an Iranian film made in Canada, nor would you say that it’s a Canadian film made specifically for Iranian speakers.

It’s part moral fable (think children navigating ethical dilemmas in the Iranian Kanoon films of the 70s, including Abbas Kiarostami’s Where Is the Friend’s House? [1987]), part confessional autofiction (an ode to Chantal Akerman’s News from Home [1976]), part diagnostic exercise in what living through a pandemic means (see Radu Jude’s Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn [2021]), and part love letter to how the magic of movies can spread joy across communities (like Michel Gondry’s Be Kind Rewind [2008]). When you examine its individual segments—two kids navigating a moral dilemma on a mission to retrieve their friend’s glasses, a peculiar tour guide leading a group through mundane Winnipeg landmarks, a grief-stricken man returning home in search of his mother—Universal Language evokes all of these films at once. And yet, when you step back to take a holistic look, it’s nothing like any of them, instead standing defiantly on its own.

Emerging from separate conversations with Rankin and his co-writer, interdisciplinary artist Firouzabadi, this interview has been knitted together to reflect shared ideas, exploring the meaning of home, belonging, community, collaboration, creating art, and much more.

Note: These interviews have been condensed and edited for clarity.

I. Mirror Cities

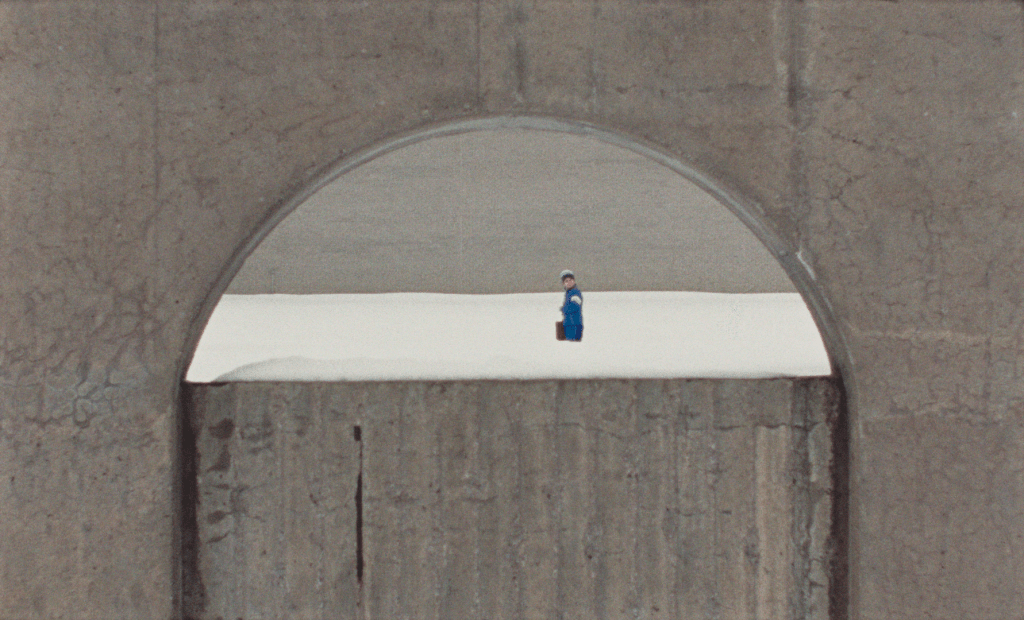

Architectural echoes between Winnipeg and Tehran—matching brutalist façades, concrete slates, and weathered hues of beige and grey—are an entry point into the comical and absurd universe of Universal Language. These cityscapes are not just backdrops; they resonate with hidden harmonies. The shared urban architecture between both cities becomes a visual catalyst to explore the potential to find things in common with people more than halfway around the world.

Matthew Rankin: Both [Tehran and Winnipeg] were built, overwhelmingly, in the 60s and 70s. It was a big era for construction in both places. And there’s a real similarity between the architecture. When I went to Tehran the first time, I was really struck by how much it resembled these beige buildings that I had grown up in back in Winnipeg. My collaborators Pirouz [Nemati] and Ila [Firouzabadi] had the same experience in an inverse way when they came to Winnipeg for the first time. They sort of recognised Tehran in Winnipeg. That is the idea of the movie. It’s about looking for the Winnipeg in Tehran and looking for the Tehran in Winnipeg. These beige structures became a sort of tuning fork because there’s an architectural echo between the two. The film is all about these improbable connections that might create proximity in spaces between which we might imagine a great distance. The architecture became an interzone through which to explore that.

Ila Firouzabadi: The first time I went to Winnipeg for the movie with Matthew, I thought I was hallucinating because of how similar it looked to Tehran. […] I also felt a similarity in the jokes and a love for dark humour. The Iranian community uses dark jokes because it’s a form of survival and a defence mechanism. That’s when I realised why Matthew, our film crew, and the Iranian community in Winnipeg became very close very fast, just in a couple of years.

II. Searching for Improbable Connections

Embracing a philosophy of in-betweenness, Rankin and Firouzabadi advocate for the embrace of transitory spaces where shared identities, friendships, and storytelling bloom. In this way, the film is less of a definitive statement by a singular person and more of an ongoing dialogue between numerous co-collaborators, stemming from a process of discovery rooted in trust, curiosity, and mutual respect.

MR: I’m a big believer in making films with your friends. Ila and Pirouz are two of my closest friends. It was a big group of friends that made this movie. The film very much is an expression of our friendship. Yes, I have been to Iran. I have learned Farsi to some degree. And I know Iranian cinema very well. This was a point of connection between Pirouz and myself when we first met each other, which was 15 years ago now. We’ve also lived a lot of things together, so collaboration is very easy. I’ve tried to return to Iran multiple times, but it’s difficult for me to go now. The ebb and flow of geopolitics has made it tricky. These days, my encounter of Iran is through my friends, and overwhelmingly, their encounter of Winnipeg is through me.

IF: After all these years, I think we realise what each of us [Matthew, Pirouz, Ila] will find funny. It’s sometimes really dark and hardcore, to be honest. Between us, Pirouz is more moderate in his sense of humour. He keeps the three of us in harmony.

MR: There is a tendency to look at the world as a system of fragments and even as a system of oppositions. We do that in politics. We do that in economics. Even on social media. But in actuality, it’s very easy to exist between spaces. And the thesis that we were kind of working from, and this is something that was very meaningful and important to Pirouz, Ila, and myself, was this notion of the ‘in-between’ space, where we have a capacity to build a loving and nurturing home. It’s not binaries that will create a loving and nurturing home, but these interzones, these spaces in-between. That’s why I used that phrase, ‘looking for the Tehran in Winnipeg and looking for the Winnipeg in Tehran.’ We were interested in looking for these improbable connections that are part of what makes us alive. We made the film in that spirit of sharing; that sharing is what makes us feel alive. The film emerged out of a long conversation and it involved stepping outside of ourselves and learning from each other and creating as we went along.

III. Being the Witness and the Storyteller

The film mostly relies on non-actors who are part of the Iranian community in Winnipeg. This blurring of performance and reality allows each scene to carry an intimacy that feels improvised but is grounded in a long-standing trust. The personal textures and lived experiences of Rankin and his co-collaborators seep into the film’s fabric in an organic way. In these portraits, collaboration becomes a form of revelation: everyone is playing dual roles, they are both actor and author, witness and storyteller. What begins as personal history becomes collective myth, filtered through the collaborative lens. Iranian cinematic traditions meet Canadian childhoods. Kleenex boxes become cultural signifiers. And in the convergence of these worlds, the film builds something distinct and resonant.

MR: Everybody is playing a version of themselves. They could express themselves personally through the prism of this movie we were making together. A lot of scenes were added while we were filming and this continued right till the end. I’m not a very regimented kind of filmmaker. I like to experiment. There’s this myth, and I think it’s a lie, about the film director being a fulminating visionary in a Napoleon hat who sees everything and is trying to control everything. For me, curiosity is an important part of being a filmmaker and that includes listening to people, because it’s ultimately a collective expression. I think of cinema as a collective form of creativity. That’s the fun of making a film. When you get a really great group together, it’s a beautiful thing. Some moments in the script that are now fundamental were not written down before we started shooting. It’s all about being open to how our collaborators wish to express themselves through the material.

IF: I’m in Tehran at the moment. There are a lot of difficulties. I came to see my parents because my dad was sick, but I still have my sense of humour to help cope with things. I know Matthew has also overcome a lot of difficulties in his life. Whatever happens, we are alive and we are making art. That’s something that we want to do. This collaboration makes us happy because we are all together. Regardless of what happens, the process of creating something together is interesting.

MR: Most of the events in the story do come from my life. My family, my parents, even my grandparents. I’m interested in the autobiographical form. A lot of the raw material comes from my life. But all of that is then fed through the prism of working collaboratively. Even if I was alone and thinking of something, it would always be at the back of my mind that this is something Pirouz and Ila would also enjoy. And I think it was the same for them. I don’t know that I necessarily would have thought to put details from my childhood in a film were it not for the fact that I was working on this story with Pirouz and Ila. For example, I dressed up as Groucho as a child. If I had different collaborators, I’m not sure I would be comfortable in being that vulnerable and including such details.

When I was growing up, there was a lady who dressed in Christmas ornaments. She had a coat made out of candy canes and another coat made of tinsel. She wore an angel on her head. She would wish you “Merry Christmas” even in the middle of August. She was just obsessed with Christmas. I loved this lady growing up and it was an event for me to see her. That’s just how she was. And I liked that. That made its way into the movie. [In the first story] The two kids [Negin and Nazgol] run into this person dressed as a tree. But they do not pass any remarks that would suggest this as something odd. They simply ask him for directions and continue on.

I guess you can say that Ila, Pirouz, and I are not ‘normal.’ This is our brand of humour and this movie is an expression of how we are together.

IF: Iranians love Kleenex. You come into our houses, it’s everywhere. In my toilet, my dad’s bedroom, my mum’s room, the other bedrooms, the kitchen, anywhere you look. Kleenex is a beloved object. One of our friends said that sometimes at a funeral people come to you and give you Kleenex if you want to cry. All the stuff to do with Kleenex in the movie comes from that cultural experience. I had written something to do with lachrymology [the study of crying] for a project years ago but never ended up using it. I told Matthew about it, that we should have a character who is a lachrymologist, and he goes around collecting tears. All of us loved the concept, so we put it in the movie.

The woman you see sitting near the turkey [Hemela Pourafzal] is one of our very good friends. She has owned an Iranian restaurant for almost 38 years in Montreal. And most of us have worked there at some point, many years ago. We bonded there and became friends. That restaurant was our meeting point about everything.

The seed of the first story, when the two kids find a currency note frozen in ice, comes from Matthew’s grandmother. That was a real story. And much later, when Matthew encountered Iranian cinema like the films of Abbas Kiarostami, he realised that there was this similarity with the moral fables of Kiarostami and the story of his grandmother. Iranian cinema has a long tradition of directors working on stories that involve a moral dilemma between adults and children.

IV. Reckoning with Collective Trauma

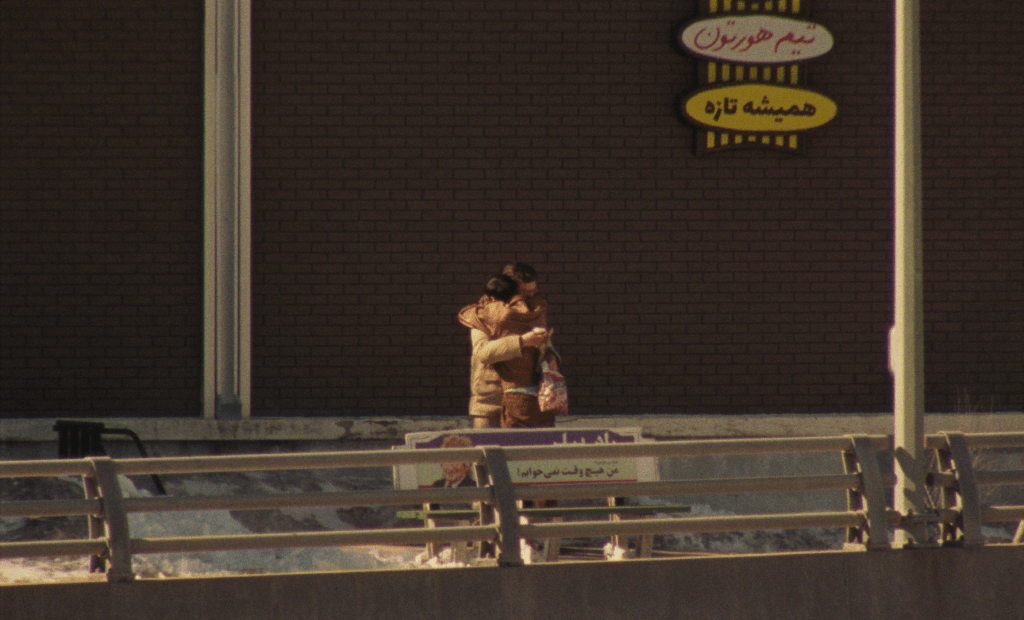

One way to approach the film is to read its dark, absurd undercurrent as a coping mechanism, a reaction to surviving a pandemic without truly reckoning with its after-effects and psychological scarring. From this global fracture, the film attempts to knit together a sense of solace, suggesting there’s a lifeline to be found in community, and in the simple act of reaching out.

MR: My observation of COVID-19 over here [in Canada] and the post-COVID world is that the solitude of that time has metastasised into something that’s beyond solitude and taken the form of an intense loneliness, something that’s akin to pathology. And I wanted to explore how to respond to this feeling. The movie works its way through great solitude, but also, it finds solace in being part of a community. There is this notion of great distance, but at the same time, great proximity. That was driven by the idealistic spirit that united Pirouz, Ila, and myself. A hope that we can form a togetherness even in this period of solitude. I don’t think we’ve really come to terms with what the pandemic has done to us in a proper way. I remember when it was happening, I didn’t know what COVID-19 even meant. What does it mean to be confined like this? It’s about trying to negotiate some of those feelings.

IF: During the pandemic, I was in Iran and I stayed for two-and-a-half years, because Canada had closed the borders. Matthew and I started to talk a lot during that time. I was in Tehran and he was in-between Montreal and Winnipeg. He was describing the situation in Canada, how there were curfews in place and people couldn’t go out. But in Iran, things were different. Everybody was out because they had to work. There was no money for the people from the government. So, even though it was a difficult time, everybody went about their normal lives. I realised how strange this was when compared to what other countries like Canada were experiencing around that time. Iran has already gone through so many traumas and difficulties, including war. People here believe this has made them more resilient and more used to hardships.

Unfortunately, many people died here too, like everywhere else around the world. Despite all of that, things did not come to a standstill here. People continued on with their lives. They were even going out to coffee shops. The whole world was experiencing a shared, common trauma, but the way we [people in Iran] were responding to it was different. Perhaps that is because the people of Iran have had far more traumatising experiences in the past compared to what living through COVID-19 was like.

The pandemic was a catalyst for us in terms of framing this film because we wanted to show that connection between people is really important. Humanity is so fluid. No matter what hardships we might experience, our fluidity as people allows us to pass through rigid systems, structures, and experiences. Just like a river. I call it a ‘rivership.’ It’s sort of an in-between space that’s part-kinship and part-friendship. It’s how we can form connections with people despite the rigidity of the world around us. That was really the seed of this film. This friendship, this connection, this fluidity.

V. Cinema as Autofiction

Beneath its playful surface, the film hides a deep melancholia. What does it mean to belong? What connects us across geography, language, and loss? For Rankin, who began this journey in mourning, this film became a way to answer these questions—or at least to sit with them.

MR: I’m a big believer that you should make a movie about whatever is at the forefront of your mind. At the beginning of the pandemic, during the first confinement, my mother died. For me, this was a time to reflect in extreme solitude about what had just happened. There were three plots that we had kind of set up. One was about the kids. The other one was about this tour guide. And the third was going to be about whatever was going on in my life at the point of making the film. This was the experimental section. We started working on this script over a decade ago.

I didn’t know exactly what my life would be like when we got to the point of starting the film. I think we are all searching for where we are from. In an existential way, this is above and beyond the normal places through which we typically identify where we’re from and where we belong. I was born in one place but I spent more than half of my life in another. I grew up speaking one language. I now live my life in a completely different language. So, where am I from and where do I belong? I think these are interesting questions. I feel very much at home between these spaces. I think that’s true for a lot of people.

When you lose a parent, when you become an orphan in particular, it’s another one of those codes of belonging where meaning begins to transform and you ask yourself these questions. The film became a medium to explore these complex feelings. The film is looking for spaces within spaces. It’s about our responsibility to others and how we build a community. How we create space for each other. The personal reflection I was going through when we were finalising the script is one that resonates throughout the film. All the pieces do connect in a way. We are all alive at the same time and that’s really amazing, you know what I mean? Like we’re all here and we’re all alive simultaneously for a very short period of time and that’s really incredible. This is the achievement of every single one of our mothers since the beginning of time. We are all somehow connected in this very complex, very improbable, very contradictory, very absurd, but fundamentally very beautiful ecosystem. It’s so unlikely that we would all be here at the same time. That’s what the film is all about for me.

VI. Being Invited to New Worlds

The film plays with language to invite multiple ways of seeing. The joy lies in these layered meanings. There are little gifts for those who can recognise them. For those who don’t, the invitation remains open. Like the cities it depicts, the film is both familiar and strange, distant, and intimate. And that is the gamble: to create a world precise enough to be real, but open enough to welcome everyone.

MR: I don’t expect anybody to pick up on anything. Nothing really hinges on that. There are little details which Farsi speakers will immediately grasp and they will have the fullest pleasure of that moment. It might be meaningful on some level if you don’t speak Farsi. But for Farsi speakers, it’s like the movie is speaking directly to them. And similarly, there are moments in French where you can’t really translate what’s being said on-screen. But if you speak French, the movie is speaking directly to you at that moment. Similarly, there is a specificity of place. The people of Winnipeg will see a few degrees more than anybody else in certain key moments, but nothing really hinges on that. It’s all about creating a world that is precise.

At the same time, this movie isn’t seeking to be an authentic depiction of the world. It is creating its own space, which exists independently of whatever reality we live in. The pleasure of a movie is always in creating a very precise space that is well-defined. That is the great joy of watching a movie. I knew a lot about Brooklyn before I ever visited Brooklyn from watching movies about Brooklyn, as I’m sure you do too. There is a way you can encounter a space that you don’t know in a movie. As long as there is a way for you to enter that world and the door is open for you and you are invited in.

I think that’s the gamble of any movie. You have to allow people to have their own relationship with it. I really like films that don’t try to tell you everything or don’t make an insistent emotional appeal to you. They let you have your own relationship with what you’re seeing. That is the essence of making art, I think. That is the difference between politics and art. Politics is about making the world very simple. But art is a place where the world is allowed to be complex.

I think the more personal we can make our films, the more it will energise us to really fight for them. I’m a big believer in making films with your friends. There is a lot of pressure to commodify cinema and turn it into something that is ruled entirely by the logic of markets alone. This can have a very contaminating effect. I don’t like anything to be transactional. Making a work of art is a very spiritual undertaking. And you have to do that with people that you are really close to. And you have to do it together. That’s what it’s all about. There’s no point in making culture if you don’t believe in community building. That is the joy and possibility of filmmaking. It’s a collective expression. It’s a beautiful thing.

That’s what I always say to people: you have to follow what thrills your soul, no matter what. There are a lot of external factors that tell you that you have to do this or that, and doing so will make people love you. But you have to just follow what thrills your soul and you have to do that with your friends. I think as long as that is the spirit guiding us, we’ll always find a way to make films. It’s never been easy to make art. You have to just go for it.

IF: In Farsi, we have this expression, “Har aanche az del bar aayad, laa-jaram bar del neshinad,” which means, “Whatever comes from your heart shall connect and reach the hearts of others.” And if this film speaks to anyone or connects with anyone in some way, that means we were able to do what we set out to do. This film has been such a beautiful learning process for me, and adding to the joy, I got to make it with some of my best friends. So, even if I don’t get to do anything after this, that’s okay. This has been such an amazing experience that will stay with me forever.

Universal Language is now screening in Australian cinemas.

**********

Virat Nehru is an Indian-Australian film critic and programmer. His words have appeared in SBS, Screenhub, The Curb, and Indian Link, among other publications and booklet essays for home entertainment releases. He is the Founding Committee Member of the Sydney Science Fiction Film Festival.

- See Page 46 of Wine of Love: Persian Ghazals of Ghalib (2022), translated and explicated by Sarfaraz Khan Niazi and Maryam Tawoosi, for the original text and accompanying English translation of the Farsi couplet in the Persio-Arabic script.

Thank you to poet Babar Imam for providing a transcription in the Roman script. ↩︎ - See Page 45 of Wine of Love: Persian Ghazals of Ghalib (2022), translated and explicated by Sarfaraz Khan Niazi and Maryam Tawoosi, for the original text and accompanying English translation of the Urdu couplet in the Persio-Arabic script.

See also the compiled critical commentary on this couplet by Dr Frances W. Pritchett, Professor Emerita, Columbia University, available online here. ↩︎