The making of a curse begins in the abode. Sprinkle a border of salt across its hardwood flooring. At the dining table, cast droplets of oil into a bowl of water. Spit blood and watch as an oily orb forms. The pot boils. The reservoir is ready. Peel the tomato with care. Squeeze its lively juices. Discard into the pot. Watch how it simmers. Listen to the summoning ripple underground. The spirit follows: a woman in black walks through the hazy, purple tunnel at Petersham station. She stops, looks down. Concern folds into shrieks of horror. Her calf peels with a thick rind of skin. Blood trails. Her body succumbs to a seizure, back panging against the concrete. A helpless silhouette in the claws of the night. Turn to the dining table once more. The bowl of water is clear.

This is the superstitious world of Salt Along the Tongue, the newly released sophomore film by Italian-Australian filmmaker Parish Malfitano, screening at Fantastic Film Festival Australia in Melbourne and Sydney after being relished by audiences at SXSW Sydney late last year. It stars up-and-coming Western Sydney actress, Laneikka Denne, as the teenage Mattia, whose adolescence is guided by two women: her birth mother, Mina (Dina Panozzo), who owns a modest small business as a fig jam seller; and Yuma (Mayu Iwasaki), Mattia’s pregnant schoolteacher and family friend. Both Mattia and Mina know the feeling of exclusion all too well: Mattia is ostracised and bullied in class, while Mina struggles to make profits from her homemade delicacies. In their quiet sufferings, they share an endearing mother-daughter bond, putting aside their daily woes to find comfort in each other’s company at home.

This bond erupts in tragedy as Mina—very suddenly—passes away. Grief-stricken, Mattia moves in with her mother’s twin sister, Carol (also played by Panozzo) and her younger partner Annika (Caroline Levien). An eccentric, wine-toting auntie, Carol pursues the more ambitious foodie career as a cooking show host for a fictional, long-running Cooking with Love series. As Mattia overcomes her grief through the newfound sisterhood of a women-led film crew, Mina’s spirit cannot escape her. Communicating through cuisine, Mattia learns to make sense of the supernatural presences that pursue her living body.

Working with a modest budget and production team, Malfitano’s film continues a legacy of independent cinema in Australia, where filmmakers rooted in DIY ethics operate without the aid of government grants. Speaking as an arts worker myself, it’s challenging to see our industry transform into a creative economy that funds, cherry-picks, and prioritises art to safely appease a general audience. Although platforms like film festivals have demonstrated a commitment to cinema culture, Australia’s screen sector seems mired in a narrow criterion of necessity over originality, ticking enough boxes to promote diversity quotas or national interests. This becomes especially difficult for many independent creatives in Sydney, where the city’s current cost of living crisis can hinder an artist’s commitment to their projects—in such frugal times, the most audacious ideas may never see the light of day. To see a Sydney filmmaker like Malfitano direct films is not only inspiring to independent creatives. It also asserts the importance, relevance, and possibilities of an underground cinema that exists outside the margins of our conformist, competitive industry today.

Salt Along the Tongue embraces its Italian predecessors, paying direct homage to the country’s giallo films of the 1970s by the likes of Dario Argento and Mario Bava: frames are stained with sensual, saturated tones of green, yellow, and purple, reminiscent of Suspiria (1977) and Blood and Black Lace (1964), while Italian women take centre stage as both victim and witness to psychological terrors. At times, we’re confronted with the decay and phenomena of women’s bodies, where legs swell with varicose blisters and nails bleed at the cuticles. They echo the female subjects of the New French Extremity films of the last decade; more specifically, the feminist horrors of Julia Ducournau (Raw [2016]; Titane [2021]), where women’s bodies communicate a visceral transformation of the self as they shed into sacrilegious abjection.

Here, corporeal mutations are driven by Italian folklore and superstition—a part of Malfitano’s heritage that he embraces with great intention and astute ability. The curse that Malfitano explores in Salt Along the Tongue is the malocchio, or the ‘evil eye’ in Italian. We do not see the malocchio appear in its all-seeing cobalt blue emblem, though this image appears in vague forms. We glimpse this in the opening, where a woman—later revealed as Nonna Rosina (Maria de Marco), a known matriarch of the supernatural—drops olive oil and blood into a bowl of water. The pupil, a blackened balsamic shade amidst blistered yellow oil, emerges from obscurity. The symbol remains unassuming yet ever-present to us as an omen.

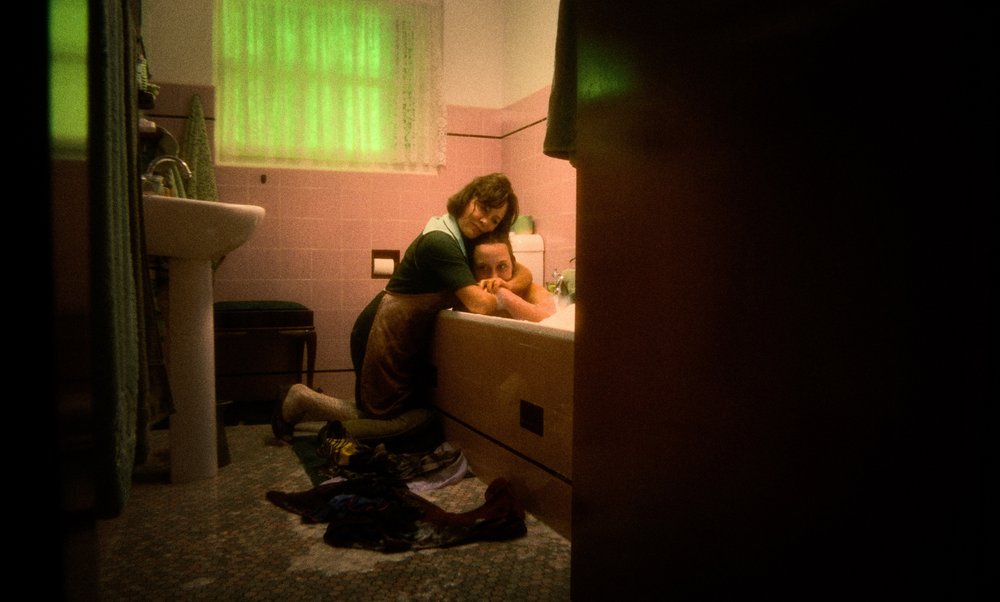

Also invisible yet essential to the film is Mina’s spirit, who looms over Mattia after her passing like a guardian angel. The film marks her presence by intermittently switching to an omnipotent first-person perspective. We encounter this the first time Mattia arrives at Carol’s home—from atop a second-floor balcony, we watch her welcomed by her aunt into the open-air atrium of a botanic courtyard, abundant with towered plant life and fig trees. In the warmth of the welcome, we play witness from the deceased Mina’s perspective. We beckon our heads down the garden, the home glowing in heavenly halation. However, her presence haunts Mattia more as an invasive voyeur than a revered protector. At night, Mattia bathes alone, her body vulnerable to the nocturnal air. We locate her down the wooden hallways, through the beaded entrance of the bathroom. A maternal gesture of care, or a terrifying, unseen omen? Mattia notices, turns her head—nothing in the darkness. Only the sense of being surveilled.

These first-person shots mirror those of the Polish-French drama, The Double Life of Véronique (Krzysztof Kieslowski, 1991), which deals with similar ideas of synchronicity between the living and the dead, as the unexpected death of Polish opera singer, Weronika, propels her soul into a French woman, Véronique (both of whom are played by Irène Jacob). Their routines, habits, and livelihood begin to parallel one another. In Salt Along the Tongue, parallels manifest between Mattia and Mina; not through the minutiae of routine, but through the consumption of food. Second-generation migrants are familiar with the role of cuisine in diasporic experiences—a bridge between the homeland and the settled country, which often consummates as a love language of compassionate gestures. However, food here disrupts this notion of tenderness, also becoming a sinister, supernatural tool for invocation; eating resurrects the dead spirit, which acts vicariously through the living to telegraph messages of resentment and malice.

In a recording session of Cooking with Love, Carol—with assistance from a quietly withdrawn Mattia—honours her sister by recreating her signature fig jam recipe. Over a cross-faded montage of cosy cooking procedures, Carol narrates with detailed trivia about the fruit’s layered, peculiar life cycle, known to propagate and ripen into fruition via a species of wasps. By the end, the two perform a taste test of their labour. Mattia smiles. “The flavour’s so good,” Carol comments, “there’s no words.” Mattia’s memory stirs—of a life that existed before Mina’s passing—but it quickly folds into a hazard. She chokes, and Annika runs to her aid, dislodging the blockage obstructing Mattia’s throat. It hurls to the ground, and we see the source of the congestion: a dead fig wasp, defiled in its own pulpy work.

Flavours ignite a nostalgia here that registers at a Proustian level; to eat is to grasp the fine fabric of the past. The memories flash into Mattia’s vision, as images of homely comforts—the fig jam stall, backyard laundry, an abundant kitchen—but as such, they are also fleeting, unable to be returned to. Mattia’s body rejects the evocations, instead invoking a corpse that only reminds her of her present grief.

These invocations are eerily gruesome at times. In a later scene, the women dine in over a sumptuous Lebanese banquet. Amidst the excitement, Mattia sheepishly asks for vegetarian options (a struggle I know far too well), before one of the women feeds her a falafel. She bites in. Seconds later, her expression sours. She tries to fish out the frittered dish from her mouth, but instead extracts a wet spool of black hair. What do these tokens signal? Mattia not only feeds herself, but a new, unseen parasite growing inside—food functions like a Ouija board between the flesh and the spirit, exchanging messages through dishes and grotesque objects. And like the female wasps that sacrifice themselves to grow figs, Mina’s spirit plants the seed for a re-awakening through Mattia’s body. So long as her daughter is well-fed, Mina can live another day.

More than a film that proudly embraces its Italian roots, Malfitano fosters a portrait of Sydney’s migrant landscape through this sisterhood of women. It’s not so much a ‘melting pot,’ but a tender tapestry of womanhood in which difference is a point of connection. They speak to one another in their respective mother tongues and, without hesitation or confusion, understand each other’s words like native speakers. At a bowling alley, Carol’s film crew comment in awe at the arrival of baked goods to their lane. Three of the women—Helen (Helen Vassiliadis), Maggie (Liz Lin), and Ola (Olga Olshansky)—revel at the sweet treats in their local languages: Greek, Chinese, and Polish. They exchange speech, candidly and with nonchalance, and we accept this as part of their dynamic. Such a female friendship embraces the multilingual as a cross-cultural gesture of platonic intimacy, transcending our knowing of these women.

More macabre, monstrous terrors unfurl across the film: flickered television sets, unexplained injuries, rapid hair loss, and—most central to the tale—demonic possessions that awaken a shadow self. However, it seems reductive to pigeonhole Salt Along the Tongue as a horror film. Beneath the narrative of bodily possessions lies a tale of complex intergenerational hang-ups and historic resentments; tropes that hit close to home for many migrant Australian families. There’s an enigma to Malfitano’s work that doubles as an examination of and dedication to migrant womanhood, strengthened with sumptuous Italian lore. Such Mediterranean flavours offer us a refreshingly ‘un-Australian’ film to savour at the table—anything to challenge our local cinema palates today.

Salt Along the Tongue screens once more for Fantastic Film Festival at Lido Cinemas on the 12th of May. See details here.

**********

Nicole Cadelina is a writer, critic, and text-based artist in Sydney (Darug). With works appearing in The Western, Tharunka, and Kill Your Darlings, Nicole’s writing reflects her diverse interests in diaspora stories and digital media. She was a recipient of MIFF Critics Campus and Varuna WestWords Fellowship. Outside her freelance ventures, Nicole interned and later worked at Sydney Film Festival for their 70th and 71st editions. Her favourite genre of film is SBS World Movies after 9pm.