“Don’t be scared. We’ll shoot right now. You only have a few lines to say.”

“I’m not scared,” was the only response from ten-year-old Elizabeth Taylor in her screen test for Lassie Come Home, MGM’s 1943 film adaptation of Eric Knight’s novel of the same name. By this point, Taylor had appeared on-screen only once, in Universal Pictures’ There’s One Born Every Minute the year prior. For this audition, she was to make believe the presence of a big, beautiful collie dog for producer Samuel Marx and director Freddy Wilcox. The young actress originally cast as Priscilla in the film, Maria Flynn, had very recently abandoned the project on account of her supposed fear of the dog. Others say the girl had a sensitivity to the Technicolor lighting, which caused her eyes to water. On this day, there was no fear in Taylor’s reputedly violet eyes.

How could anybody have known the menagerie that would become Elizabeth Taylor’s life? Hers is quite literally a tale of lions and tigers and bears, too often only remembered as one of husbands, private jets, and jewellery. From her earliest days in the spotlight, Taylor was defined by performances with an animal at her side. This was true of the Lassie films and then again with 1944’s National Velvet, all of which were great box-office hits. Hear it straight from the horse’s mouth: “Some of my best leading men have been dogs and horses.” This was also true behind-the-scenes. Her much written-about love affairs included, but were not limited to, dalliances with parrots, ponies, and Pekingese.

* * * *

A litter of little dogs starred in Taylor’s long life. In fact, the volume of terriers, spaniels, and dachshunds remains undetermined. During her marriage/s to Richard Burton, she supposedly kept a yacht on the River Thames that housed her many pets, quarantined there for fear of spreading disease ashore. “It was a floating kennel,” according to biographer Roger Lewis. “None of them were house-trained. Elizabeth would simply say, ‘Just replace the carpets!’”1

Unflattering portrayals of animal-Elizabeth followed her from the very start. The sometimes-hateful biographer Lewis went so far as to conflate Taylor with her animal companions, insinuating that she might as well have contracted rabies living like she did. Other biographers, like Ruth Waterbury, claimed that Taylor was born “covered with black fuzz” head-to-toe.2 These comparisons are seemingly inseparable from her legacy. In the hit HBO series Sex and the City, Charlotte (Kristin Davis) keeps a cavalier called Elizabeth Taylor.

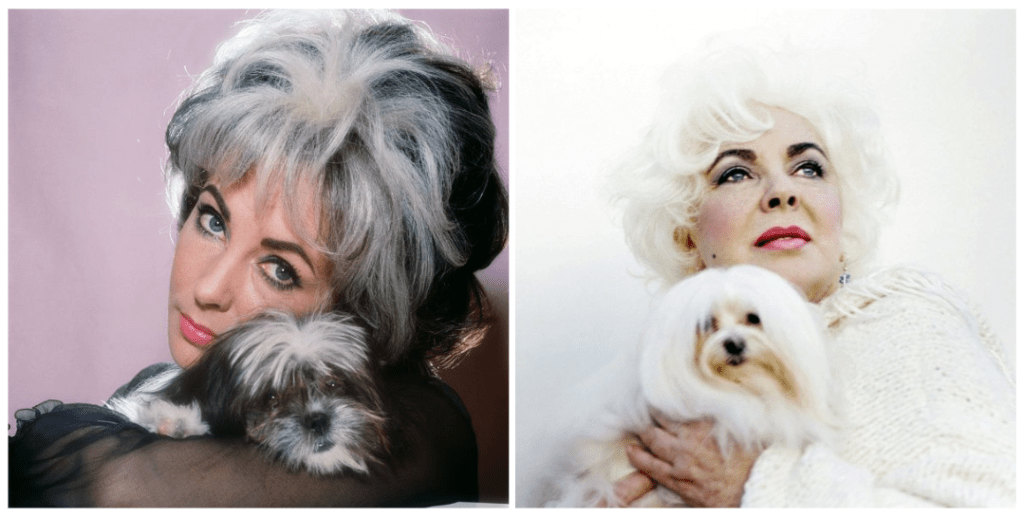

I have found no evidence of Taylor ever keeping a cavalier herself. There was the Yorkshire Terrier who appeared briefly as her canine companion in BUtterfield 8 (1960). Or the Shi-Tzu, named Mariposa, with whom she posed for British Vogue in 1972 while donning a matching, grey-streaked wig. Or the collie—a great-grandchild of the dog who played the original Lassie—she fought for custody over during her final divorce. Then there was her greatest love of all, Sugar, who never left her side. After the tragic loss of Taylor’s then-husband Mike Todd in the fifties, her volatile on-again, off-again marriage/s to Burton in the sixties and seventies, and the nineties camp spectacle that was her wedding to Larry Fortensky, this white Maltese terrier became her other half in old age.

She once said of Sugar, “I’ve never loved a dog like this in my life. It’s amazing. Sometimes I think there’s a person in there.” The dog became a star in its own right, dining at restaurants and appearing on talk shows with Taylor. The pair were a match made in heaven—match, the operative word. As Taylor’s hair started to grey, it quickly resembled that of the white mop under her arm. In 1998, Sugar was immortalised as a Christmas ornament by Christopher Radko. Proceeds went to the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation. The ornament was an anthropomorphic depiction of the Maltese terrier holding up a framed image of itself and Taylor making a kissy face, as if to say, “Merry Christmas!”

Other cherished canines include her first pet Monty, the golden retriever her family adopted on the day she was born in 1932. It was a funny coincidence that as a young ingénue Taylor would go on to form a cherished friendship with the great movie star Montgomery Clift. The two starred across from one another in three films—A Place in the Sun (1951), Raintree County (1957), and Suddenly, Last Summer (1959)—and were incredibly close until the untimely death of Clift in 1966, which meant he was replaced as Taylor’s abiding co-star by Marlon Brando in John Huston’s 1967 Reflections in a Golden Eye. When asked about Clift and Brando by Rolling Stone Editor Jonathan Cott in 1987, Taylor credited both actors’ mastery of their craft to their vulnerability and “acute animal sensitivity.” “To me, they tap and come from the same source of energy,” she mused.3

Certainly, this was the same quality that attracted her to the child-like Michael Jackson, with whom she shared a profound friendship for more than 20 years. Too often their relationship is chalked up to like experiences with child stardom. Few seem to recognise the spiritual dimension of their friendship that rendered their souls symmetrical and so often expressed itself in their love of animals. Taylor famously gifted Jackson a five-tonne elephant named Gypsy, to live in his infantile petting zoo, Neverland Ranch. As Lewis put it, Taylor responded to the “animal in man.”4 She believed that animals were manifestly capable of unconditional love. Love: the essential force in her indelible life.

* * * *

Quoted talking about one of her fragrances in 1987, Taylor said:

“An interviewer asked me what quality it was in me that made me the survivor that I was … I think it’s my passion. My passion for life, for people, for caring, my passion for everything. I’m not fascinated by things. I dive into them. One is fascinated by fire. But when I was a toddler and crawling, I was so fascinated by it that I reached out and touched it. That’s the difference between fascination and passion for me.

You cannot have passion of any kind unless you have compassion. If [you] don’t have passion, it means [you] are incapable of love. That passion has just always been there and I’ve taken it for granted. I still have that childlike ability to get diverted by my own thoughts. Because I’m not afraid. Life is just such an adventure to me.”5

* * * *

Lassie Come Home launched the careers of two iconic MGM pets that would soon become house-trained household names. In her many years on screen, Taylor would learn to stay (in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof [1958]), to roll-over (in Cleopatra [1963]), to shake hands (in The V.I.P.s [1963]), and finally to bark (in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? [1966] and Boom! [1968]). In her minor role in Lassie Come Home, Taylor’s scenes bookend the story. True to form, she plays a well-behaved posh little girl, Priscilla, with excellent posture and a love of animals. This was a natural fit for Taylor; her father was an art dealer, she lived in a home with a tennis court, and she fancied riding her Newfoundland pony in her downtime. “When I am making a picture I am always in bed at eight o’clock, and I study my lines from eight to eight-thirty.”6

The other studio pet, Pal, was first introduced to the world on the big screen as Lassie, the prized pooch of a humble Yorkshire family, the Carracloughs. Concerned that they might not be able to put food on the table for their son Joe, the Carraclough parents make the difficult decision to sell their beloved family pet. Joe, who shares a special bond with Lassie, is devastated by the loss of his best friend, and as Lassie Come Home never allows us to forget, so too is the collie. After digging holes and jumping fences to return home to the Carraclough household, Lassie is taken to Scotland by her new master, the well-to-do Duke of Rudling, and his granddaughter. But Lassie must fulfil her promise to always come home, and so she fearlessly embarks on an unbelievable expedition, travelling hundreds of miles, to get back to her family in Yorkshire.

The title Lassie Come Home reads as the sequel to a movie simply called Lassie, although in fact it was the first of its kind. It hints at something before itself. The ‘before’ in this case being the complete family, still recovering from the fragmentation of war. The story is told in three distinct acts, with a great journey as its middle part. Importantly, the verb bridges the gap between the two nouns, and is the force that determines whether Lassie will ever find her way back home. In another reading, the title is a speech act: “Come!” It’s something one might call out to a missing dog. Then again, Lassie is never asked to come home. She is Lassie Come-Home. As Joe would have it, “Ye’re my Lassie Come-Home. Lassie Come-Home. That’s thy name! Lassie Come-Home.”

In Lassie Come Home, Priscilla is unnaturally composed, at times eerily doll-like. While watching the story unfold, the sense that Priscilla has begged her grandfather to buy her the collie emerges, though this is never actually shown or expressed. We are left to assume that Lassie was a gift for the Girl Who Had Everything (as if predicting Taylor’s iconic role in the 1953 film of this name). The producers of the film seem careful not to demonise the little girl, however necessary her brattish demands may be to the progression of the story. Instead, she is imparted with pure altruism, heroically leaving a gate open for Lassie to escape her new home in Scotland. Then again, back in the final scene, she pretends not to recognise Lassie to allow her to stay with her rightful family in Yorkshire. Everything hinges on her ability to pretend, just like it had for a young Taylor in her screen test.

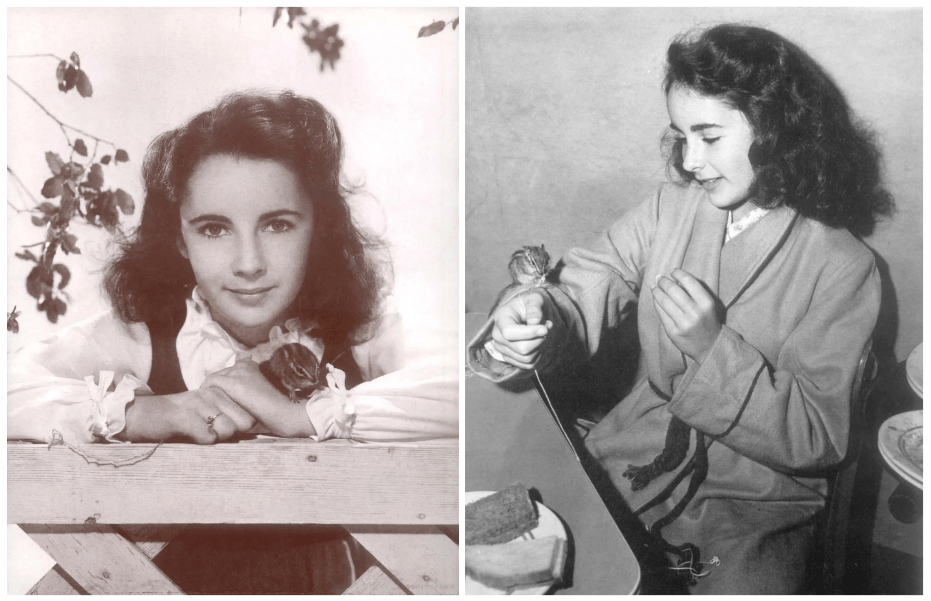

Taylor’s career (and life) can be divided into three distinct chapters; the pets (the Lassie films, National Velvet [1944]), fathers (Life with Father [1947], Father of the Bride [1950], Father’s Little Dividend [1951]), and husbands, of which there were infinite (Giant [1956], The Sandpiper [1965], et cetera). Taylor’s tabloid life of opulence and never-ending ceremony seems to overshadow her animal mysticism. At 14, she was published as both author and illustrator of a book called Nibbles and Me, about the adventures she shared with her pet chipmunk. Taylor’s biographer, Lewis, who admits to wanting to step on the rodent, frames Nibbles as a premonition of the actress’ marriages, where she “coos over his antics” and “weeps over accidents and disasters.”7

The same year Nibbles and Me was published, in 1946, Taylor starred in Courage of Lassie as Kathie, a plucky tomboy from the Pacific Northwest. The first 20 minutes of the film play like a Technicolor silent film acted out by bears, coyotes, skunks, a fox, a lizard, a squirrel, a beaver, a bobcat, a golden eagle, a raven, and a collie dog—a field day for the girl who could talk to animals! In Nibbles and Me, Taylor describes the opening sequence of the film as “a wonderful symphony.”8 In Courage of Lassie, Kathie is the dog’s guiding light. As she is reminded by her mentor, the rancher Harry MacBain, “a man goes to church to talk to a god he can’t see. But a dog can see his god that he loves, and talk to him and obey his commands all day long. All he wants is to love you and have you tell him what you want him to do.”

In Nibbles and Me, Taylor recalls talking to her Newfoundland pony, Betty. “I told her that she had been given to me, and that I was her new mistress, that I loved her very much and wanted her to love me.”9 Once again, dialogue from her films bleeds into her testified memories. She turns saccharine remembering Betty, who would accept only her as mistress, bucking off other riders and scaring them away. Taylor chalks this up to nobody loving Betty quite like she did.

“What does it feel like to be in love with a horse?” In her first starring role, the 12-year-old Taylor plays Velvet Brown in National Velvet. Acting across from Taylor (both actors stand 1.57 metres in height) is 24-year-old Mickey Rooney as the young vagrant Michael ‘Mi’ Taylor. Velvet belongs to a family of idiosyncratic animal lovers. Her sister Malvolia speaks only of canaries and her kid-brother Jackie ‘Butch’ Jenkins collects insects, keeping them in a bottle around his neck. An absorption in animal species is naturalised as being innate to the Brown family, another overlap between the character and real-life persona.

Unlike other girls her age, Velvet is introduced as being disinterested in boys. Her idée fixe is simply ‘horse.’ When she crosses paths with Mi on the outskirts of Sewels, Sussex, together they discover the gelding at the centre of the story, a horse called ‘The Pie.’ This moment of love-at-first-sight is also one of near-death, as Velvet is almost trampled after launching in front of The Pie running at full-speed—a fearless moment made possible only with rear projection. Why does the horse choose to spare her? It is not simply that she is ‘keen on’ horses as suggested, but that she is connected with them on a psychic, even supernatural level.

* * * *

“As they say, ‘Don’t look into a lion’s eyes.’ I had that happen once when I was in a jeep in the bush of Africa, in Chobe. And I came upon this black-maned lion just in the middle of the forest. We were in this totally open jeep And I said, ‘Go very slowly, just make as little sound as you can.’ And we got a little bit closer—so close, in fact, that I could see the hairs on this animal’s body.

I’d never seen anything resembling this lion. I wanted to get really close. And the animal by this time was looking at me, and [the guide], who would not look at him, said, ‘Elizabeth, stop staring into the cat’s eyes.’ And I said, ‘I’m sorry, but I can’t take my eyes away from this.’ And this cat and I are staring into each other’s eyes. And there was no power in this world that could make me take my eyes out of that cat’s eyes. And the lion opened his mouth, and I saw these teeth, I could see strings of saliva attaching the teeth as he yawned, and he let out a roar that didn’t make me jump—because it’s as if I knew what he was going to do.”10

* * * *

In National Velvet, the horse and the girl are diametrical in nature. Where The Pie is wicked (“He’s got the devil in him”), Taylor as Velvet is reverent, even saintly (“Every day I pray to God to give me horses, wonderful horses”). Is their attraction a consequence of opposite electric charge? Or are there other forces at play? In the unlikeliest of circumstances, Velvet wins The Pie in a raffle because she “arranged it with God.” Providence is treated as a rationale, as if to acknowledge that God’s intervention is the guiding hand of the producer moving the story forward.

When The Pie becomes gravely ill, Velvet speaks to it directly: “Tell me what hurts, I’ll understand.” Are they telepathically connected, like Elizabeth and Nibbles, Betty, or Sugar? Like in Lassie Come Home and Courage of Lassie, Taylor’s ability to make-believe an affinity with her animal scene-partner is supported by her very real affinity with the creature. In the widespread imaginary, the artificial or on-command tear shed on-screen or stage by the actor is summoned by the memory of something truly sad and very much real. In this way, the tears of an actor are paradoxical, in that they are especially true. The same sophistication exists in the performance of 12-year-old Taylor, whose watery eyes in National Velvet are moved beyond the limits of the childlike make-believe.

Importantly, Velvet the girl is promoted to National Velvet the headline in the final act, when she surreptitiously competes in and wins the grand national tournament. Her disguise is a bright fuchsia jockey’s cap and silk costume. With the help of the ever-present Mi (Rooney, offering a reminder that 12-year-old Taylor with a haircut could pass as an adult male any day), Velvet’s success is a contingency that is at once impossible and fated. For the duration of the almost 15-minute race scene, the eye is asked to find the pink jockey, and in doing so, identify the girl among the men.

There is some confusion that surrounds the actual riding in National Velvet. There are widespread claims that fearless Taylor did not have a stunt double. How can this be true? In fact, it is not; Alice Van-Springsteen was Taylor’s stuntwoman. The popular factoid is perhaps a conflation indexed by stories of Taylor’s lifelong spinal issues that began with an important horse-riding accident on the set of National Velvet. In the words of Rooney’s Mi: “What’s a horse? An animal that earns his keep until he breaks his back.” And what of an actress in the studio system? Is she also an animal, one that earns her star until she breaks her back?

In Nibbles and Me, Taylor makes a confession that ‘Nibbles’ was, in fact, a cavalcade of chipmunk duplicates. Squashed by a door, she recalls, “I can hardly write about him without feeling such a pull at my heart, and yet I know that even though he seemed to die, he really just passed out of my sight; because ‘Life’ doesn’t die.”11 Life doesn’t die? Nibbles ‘the first’ was replaced by a series of understudies—seven, to be precise.

Thinking she had outsmarted death, Taylor bragged that Nibbles would “never grow up and never grow old.” This book was sold as the story of a young girl leaving her childhood behind. In retrospect, Elizabeth Taylor would never grow up, but she would grow old. In her seventies, she was photographed by Bruce Weber reading Nibbles and Me to a grizzly bear named Bonkers. Weber later said in memoriam of the star, “Of course Elizabeth was late and any other star besides Bonkers might have been irritated about it but the moment they met they instantly had a strong rapport.”12 Other images capture the black bear and Taylor leaning in for a kiss.

**********

Charles Carrall is a writer and critic from Sydney, Australia. He makes up one half of the podcast Vanity Project.

- Roger Lewis, Erotic Vagrancy: Everything About Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. Riverrun, London, 2023, p. 48 ↩︎

- Ruth Waterbury, Elizabeth Taylor: Her Life, Her Loves, Her Future. Popular Library, New York, 1982, p. 10. ↩︎

- Taylor, quoted in Rolling Stone Elizabeth Taylor: The Lost Interview, 1987, published after her death in 2011. ↩︎

- Lewis, p. 434. ↩︎

- Taylor, quoted in Rolling Stone Elizabeth Taylor: The Lost Interview. ↩︎

- Elizabeth Taylor, Nibbles and Me. Duell, Sloan, & Pierce, New York, 1946, p. 5. ↩︎

- Lewis, p. 25. ↩︎

- Taylor, Nibbles and Me, p. 5. ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 2. ↩︎

- Taylor, quoted in Rolling Stone Elizabeth Taylor: The Lost Interview. ↩︎

- Taylor, Nibbles and Me, p. 11. ↩︎

- Weber, quoted 2020 via Facebook. ↩︎