“Her music has this slightness and subtlety, and really develops quite gradually. There’s something […] that does not necessarily resolve so easily,” says writer-director Ryusuke Hamaguchi of the work of musician and composer Eiko Ishibashi.

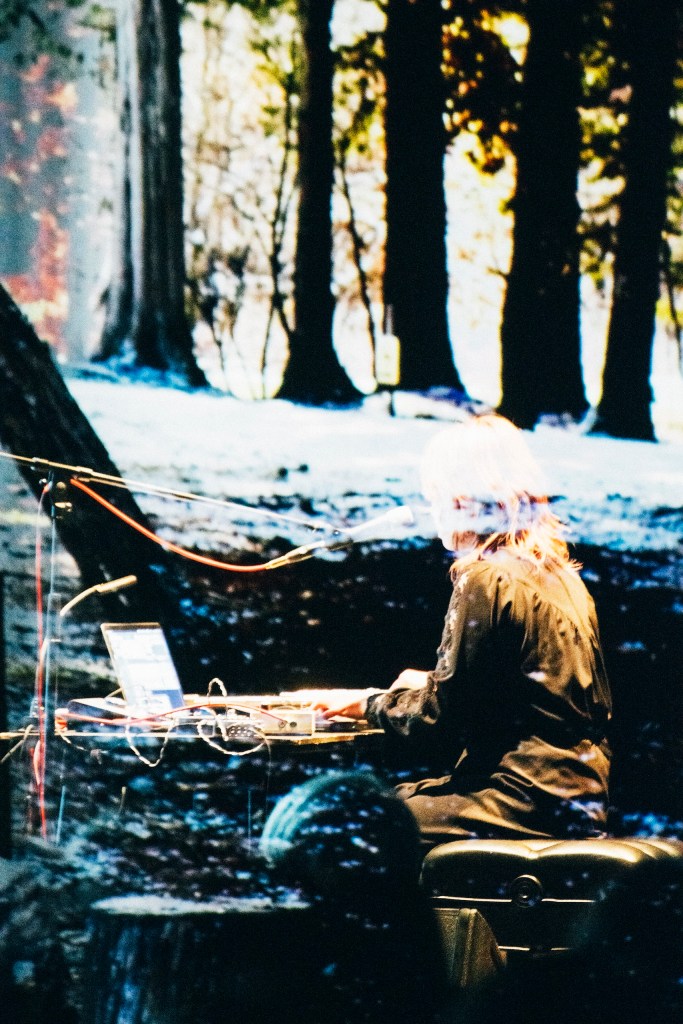

Following her collaboration with Hamaguchi on Drive My Car (2021) and Evil Does Not Exist (2023), this April and May Ishibashi brings their inquisitive audiovisual work GIFT to Australia with performances in Brisbane, Melbourne, and Sydney. Ostensibly a silent film re-edit of Evil Does Not Exist with live music accompaniment, GIFT is actually the original form of the project, instigated when Ishibashi was offered to stage a series of performances to accompany visuals. Uninterested by the prospect of playing in front of an abstract experimental video, she approached Hamaguchi to create a visual narrative piece for her to respond to.

Reversing the more traditional composer-director relationship that defined the jazz-influenced soundtrack for Drive My Car, Hamaguchi devised the narrative of GIFT and Evil Does Not Exist following a year of email conversations with Ishibashi, and a period staying in her home region of Yamanashi Prefecture. Channeling the ecological and political issues faced by residents in the area, the films’ shared narrative is—like Ishibashi’s shifting rock-electronic-classical soundtrack—conflicted, parabolic, and unresolved, suggesting the unsustainability of a world out of balance.

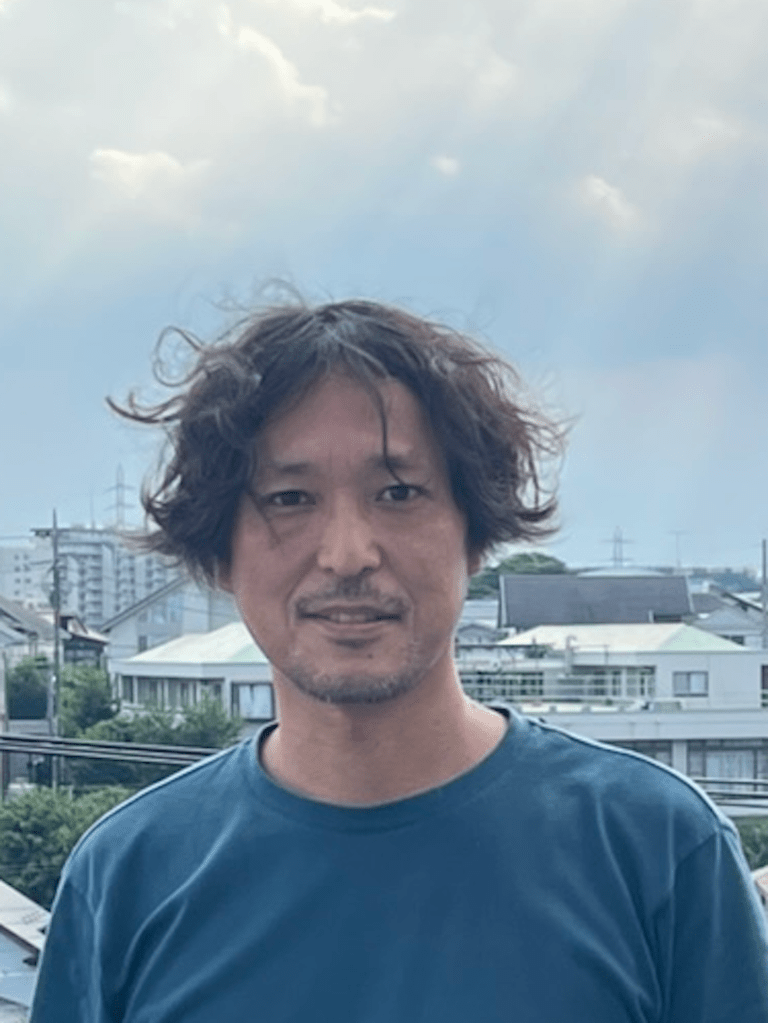

Joining Ishibashi for her Australian performances is Satoshi Takata, producer of GIFT and Evil Does Not Exist. A long-term Hamaguchi collaborator, Takata previously co-produced the director’s five-hour epic ensemble drama Happy Hour (2015) and related short Heaven Is Still Far Away (2016), and solely produced his anthology film Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (2021). Friends since their university days, their journey together is a beacon for young cineastes around the world: evidence that truly independent filmmaking is still possible. Speaking to Takata and Ishibashi separately over email, they each revealed an openness to the creative process and a patient sensitivity to the world around them.

Note: The following interview interweaves their comments to resemble a conversation and has been edited for length and clarity.

Andréas Giannopoulos: Satoshi, you’ve produced many of Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s films, starting with Happy Hour in 2015, which was also your first film as producer. How did your relationship with Hamaguchi start?

Satoshi Takata: Hamaguchi and I have been friends since our university days. We were in the same film club where people made independent films, and we also attended a study group on film theory organised by a TA. Back then, we were simply fellow students with a shared interest in cinema.

After graduation, I began working in the IT field, while Hamaguchi continued making films through vocational school and graduate studies. I had no experience in professional film production, but after he completed the Tohoku Trilogy with co-director Ko Sakai [The Sound of the Waves (2011), Voices From the Waves (2013), and Storytellers (2013)] I heard that he was planning to conduct a workshop in Kobe for several months, and afterward, make a fiction film with the participants. At that stage, very little had been decided beyond that basic concept.

It was then that I was introduced to Hideyuki Okamoto, another longtime friend of Hamaguchi and the co-producer of Happy Hour. At the time, I was co-running a small software development company (NEOPA) with two partners, and after getting their agreement, I contributed a small amount of funding to the project. In that sense, Happy Hour felt like a grown-up version of the independent filmmaking we had done as students—just on a slightly larger scale.

AG: Eiko, you’ve spoken before about how the dual projects of GIFT and Evil Does Not Exist came about. Can you tell me about the key ideas that you contributed to the project, and how these translated into the music?

Eiko Ishibashi: I had been talking with Hamaguchi about this project for about a year since I asked him about it, exchanging emails and having casual conversations with him.

The topics that came up: forgotten places, memories of the land, garbage and the city, and so on, may have influenced the work in retrospect, but my direct contribution was only the music. When the topic of garbage and dust came up, I made a musical demo about it, which became the axis of the soundtrack.

AG: How did those two particular topics translate into the music, and how did this demo then expand into the rest of the soundtrack?

EI: I think I made it with an awareness of things that are always moving and cannot be undone. I used a lot of synths.

ST: I first heard about the collaboration between Ishibashi and Hamaguchi at the end of 2021. Then in January 2022, I met with Eiko, her manager Yuri Yoshioka, Hamaguchi, and the four of us sat down together for the first time.

At that stage, I wasn’t involved as a ‘producer’ in the conventional sense. No one really knew yet what we were making or where it was headed. I was more like an observer, listening as the two artists began sharing ideas, and vaguely thinking that my role would be to help shape a production and release framework later, once their vision became clearer.

This was nothing like a typical film project, where you’d normally establish the scale, release timeline, and distribution plan in advance and secure a budget before shooting. The only defined goal was to create a live performance with music and moving images. Financial considerations were temporarily set aside; what mattered more was the creative process itself—two artists working together across disciplines. That, in and of itself, felt valuable.

So I took the approach of, “Let’s see what this becomes—then figure out what to do with it.”

AG: What do you feel are your responsibilities as a producer, particularly when working with a writer and director as distinct as Hamaguchi?

ST: I believe my role is to do as little as possible unless absolutely necessary, and to let the director decide what needs to be done. My job is to stay close by as things take shape, watch over the process, and quietly remove the obstacles that appear along the way. It’s a behind-the-scenes role—perhaps even behind those behind-the-scenes.

Especially when working with a director with a strong personal vision, I think the way the film eventually finds its audience becomes all the more important. I don’t want to force it into the world, but I do feel a responsibility to ensure that, if there’s even one person out there who might find the film compelling, it reaches them. That person might be someone sitting beside me now—or someone not yet born, fifty years from now.

AG: How did you manage the different requirements of both GIFT and Evil Does Not Exist while producing the projects simultaneously?

ST: To be honest, I never felt like I was producing two projects in parallel. The initial spark came from the collaboration between Ishibashi and Hamaguchi for the live performance piece. From that foundation, Hamaguchi began working on visuals using his usual filmmaking methods, and even though the idea was to ultimately create a silent work, he still wrote a full screenplay with dialogue.

But as the shoot approached and he heard the actors’ voices and performances, he began to feel that the material could stand on its own as a film. Ishibashi agreed and, out of that natural progression, Evil Does Not Exist began to take shape as a separate project.

So no, there were no requirements, hence no particular management strategy or clever coordination. If anything, my only ‘strategy’ was to observe quietly, not worry unnecessarily, and enjoy watching the project evolve organically.

AG: How does the music for GIFT differ from the score of Evil Does Not Exist?

EI: The music for GIFT is basically improvised. I also use material from the music for Evil Does Not Exist, but it changes every time because what I am experiencing while watching the visuals is directly reflected in the music.

AG: GIFT has been staged in different parts of the world over the last 18 months. Has the performance developed in a particular direction over that time?

EI: I don’t think we are going in any particular direction in a linear fashion. Each time the venue is different in size and sound, so what I do will change depending on the space. Looking back ten years from now, maybe I’ll realise it was heading into something, but I don’t see what that is yet.

ST: The screening at QAGOMA marks the fifth time I’ve experienced GIFT in a public setting. Rather than feeling that Ishibashi’s performance has developed in any one specific direction, I’ve found myself consistently surprised—each time offers new discoveries in how the music is used and how the piece is performed. I’m especially looking forward to this one, as it’s been a while since I last saw it.

AG: Eiko, the films were shot near where you live in Yamanashi Prefecture. How do you feel about the way the area is presented in the two films, and did this impact how you composed for them?

EI: Hamaguchi did a lot of research around my neighbourhood, so I think this is a realistic depiction of the problems facing the countryside and the way the people here are. And since the initial idea for this project was a visual work for a live concert, and Hamaguchi’s starting point was to make a film in an environment where I make music, I think the images and music blend well together.

AG: Do you have the same environmental and political concerns that Hamaguchi explores in the two films, and did these shape your approach to the music?

EI: I don’t think Hamaguchi specifically wanted to explore political or environmental issues in this film. However, it is difficult to ignore political and environmental issues in our daily lives or when creating something. I also could not ignore them when making my new album Antigone.

AG: The themes do seem to be a departure from Hamaguchi’s previous fictional films. Or perhaps, they can be thought of as a meeting of his narrative work with his prior documentary work. Satoshi, did this affect how the two films were produced and distributed?

ST: Hamaguchi’s process involved close cooperation with local residents, and the places and lives that emerged from that research are directly reflected in both GIFT and Evil Does Not Exist. We did not set out with the intention of focusing on environmental or political themes. That said, I believe such elements inevitably surface—one way or another—when depicting human life.

For this reason, we hoped audiences would experience what is seen and heard in the films just as it is, without the filter of over-explanation. In domestic distribution, for example, our publicity producer Motoaki Aoki deliberately avoided promotional phrases that might lead or mislead the viewer. Instead, he used the line, “This will become your story,” as a quiet invitation to each individual.

AG: For you, are there any differences between the meaning of GIFT and the meaning of Evil Does Not Exist?

ST: The biggest difference for me lies in the improvisational nature of GIFT. Cinema, by nature, is reproducible. Once completed—with its sound and image fixed—it’s designed to be the same no matter how many times you watch it. GIFT breaks that convention. While the visual component remains the same, the live musical performance changes with each iteration, giving the film a completely different tone and feeling. Even though its narrative framework closely mirrors Evil Does Not Exist, the experience transforms radically depending on the sound.

AG: GIFT has frequently been classified as a ‘silent film.’ Eiko, when composing for GIFT and Evil Does Not Exist, were you interested in silent films from early cinema and the way music is composed for them?

EI: Yes, I found it very interesting when I worked previously on several silent films with live music. For The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), I performed with multiple recordings of voice and flute, but I think I was mainly concerned with volume. For Metropolis (1927), I played synthesisers and percussion.

I thought it would be important to know how to create the blank spaces, because I basically don’t think music is necessary in a film. I shared these ideas with Hamaguchi, and that is how this project began. We are doing the GIFT tours to examine the relationship between music and visuals.

ST: Because Evil Does Not Exist exists as a finished reference point, GIFT doesn’t feel like a typical silent film with live accompaniment. Rather, it feels as though a new ‘sound cinema’ is being generated each time it is performed. It’s been almost a century since the advent of the talkie, but I believe GIFT provokes us to re-examine the question: What is sound in cinema? And it does so in a way that’s both playful and deeply provocative.

The Australian performances of GIFT begin at the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, where they run until April 26, presented as part of the Asia Pacific Triennial Cinema: Ryusuke Hamaguchi season.

Ishibashi and Takata will also participate in an In Conversation event at QAGOMA on April 27.

Further performances of GIFT will take place at the Melbourne Recital Centre on April 28 and the Art Gallery of NSW on May 3 and 4.

**********

Andréas Giannopoulos is a Melbourne-based filmmaker and co-curator of the Melbourne Cinémathèque.