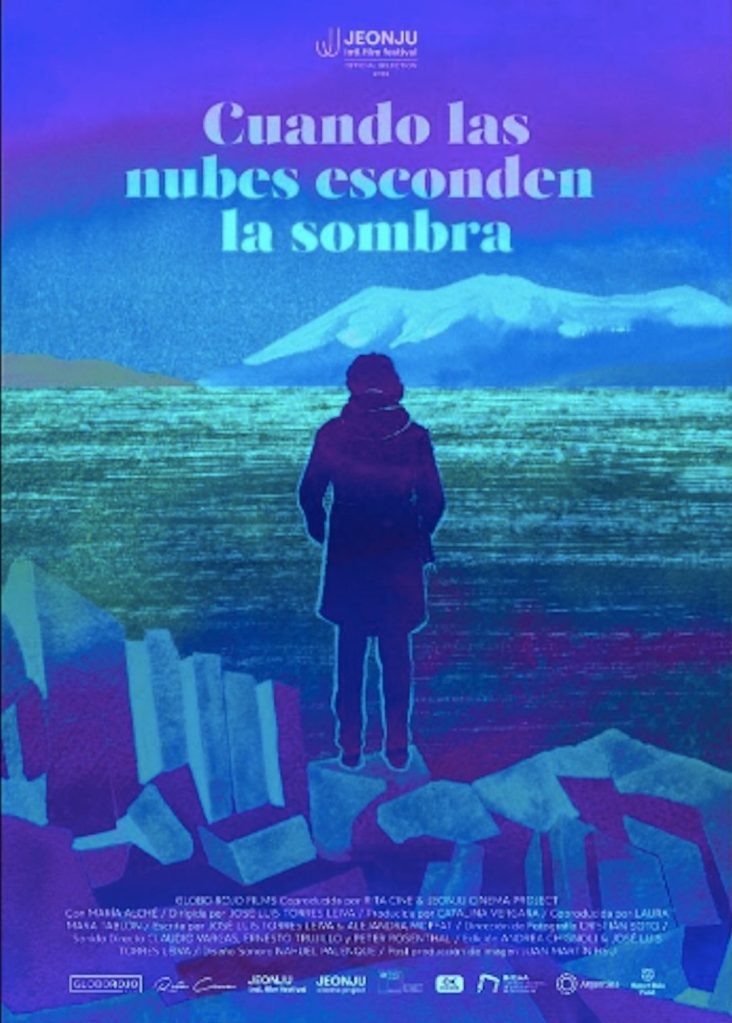

The plot, much like the film itself, is simple: María (María Alché) is an actress who travels to Puerto Williams to star in a movie, but a strong storm prevents the rest of the crew from arriving on time. María is left alone, waiting and interacting with the town’s inhabitants. She observes this place—a village at the edge of the world—which, in turn, seems to gaze back at her. In many ways, one could say that Cuando las nubes esconden la sombra / When Clouds Hide the Shadow (2024) is about a film that never gets made. Yet, it is also about unresolved stories in the lives of both the filmmaker and María—blurring the lines between the real and fictional María—as though the film itself were exposing and soothing their wounds within its seventy-minute runtime. When Clouds Hide the Shadow is, among other things, a healing work of the imagination and a simple yet profound cinematic experience.

As part of the 28th Santiago International Documentary Film Festival (FIDOCS), I sat down with José Luis Torres Leiva1 and María Alché2 for a public discussion that explored their ethics of care and amicable approach to filmmaking. In collaboration with FIDOCS School, Rough Cut is thrilled to present an excerpt from Torres Leiva’s and Alché’s intimate dialogue, ahead of the film’s Australian premiere at the BBBC at Gallery Gallery Inc in Brunswick this June.

Note: The following exchange between filmmaker and actress took place in Santiago de Chile on November 20, 2024. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

María Alché: I’d like to begin by asking what motivates you to make a film? You are an incredibly prolific director, and whenever I watch your work, I always wonder about that initial impulse to tell the story.

José Luis Torres Leiva: I think that varies for everyone, and each filmmaker has a deeply personal process. For me, many of my projects begin with a place—a space that captivates me and affects me on a personal level. That feeling, that connection with a place, stays with me throughout the entire process of making the film, from finding the story and writing the script to deciding how to tell it. But each process, like each place, is unique. That’s been very important for me: understanding that no two films are alike and that you need the right space to get close to the story, to create the images that will ultimately tell that story.

MA: Right, and over time, as you make films, you start to develop your own approach to these creative processes—whether it’s writing or shooting…

JLTL: Exactly. And for you, how much space do you give to the actual shoot? How much does your experience as an actress influence the scripts you write?

MA: When I started studying film at Argentina’s National Film School—a public institution—they had a very structured system. The script was written by someone studying screenwriting, and the person directing, like me, focused strictly on direction. The school’s approach to organising the work was so rigid that it made it hard to experiment. The cinematography students had to focus solely on the visuals, the sound students on sound, and so on. Within that structure, I found it really difficult to learn anything new.

After graduating, I started inventing projects that allowed me to experiment and explore. I created low-budget setups that I could afford, and being an actress helped me relate to my films from multiple perspectives—both behind and in front of the camera. Acting also seeps into the writing process. I notice it when I write: I place myself in the characters’ shoes and spend hours trying to achieve something real. For me, a genuine acting moment happens when I stop thinking and something magical unfolds. The space transforms, and suddenly, the set, the crew, and the camera disappear. It’s almost mystical. I think something similar can happen when writing scripts. You immerse yourself in the characters’ emotions, and the scenes gradually emerge with their own rhythm, movement, and duration. This includes not just the characters’ physical movements but also the objects they handle, the words they speak, and the silences they hold. Writing scenes helps me better understand who the characters are and how they feel. It’s a process closely tied to acting, which also involves trial and error. When you’re on set, the scene starts from the impulse to tell a story, but then comes the acting—letting go of everything. When the actors gather on set, something shifts; something about the mise-en-scène changes the script, and the shoot forces you to adapt.

José Luis, I love Raúl Ruiz’s book Poetics of Cinema (1995). I often revisit it when I teach, especially his ideas about the central conflict. How do you think a film sustains itself? What structures or forms give space to conflicts that don’t seem central at first? I’m thinking of those smaller, everyday conflicts in your films that slowly connect to larger ones.

JLTL: I believe it’s absolutely possible to make films that focus on microscopic conflicts, zooming in on everyday phenomena. For me, connecting with these smaller conflicts is driven by emotion, and it’s from that place—what happens in and with the space—that a script structure begins to emerge. With my last two films, El viento sabe que vuelvo a casa / The Wind Knows That I’m Coming Back Home (2016)3and When Clouds Hide the Shadow, the scripts were initially written to apply for documentary funding. These films blur the line between fiction and documentary. For The Wind Knows That I’m Coming Back Home, Tiziana Panizza4 and I travelled to Chiloé Island, where the film was shot. We immersed ourselves in the place and spent time talking to the locals. That experience shaped the script, but by the time we started shooting, almost nothing from the script remained. The idea of Ignacio [Agüero] as a director conducting a casting session on the island was in the script, but the encounters he had with the people on camera emerged naturally during the shoot—as if the film were being created in real time.

I believe it’s absolutely possible to make films that focus on microscopic conflicts, zooming in on everyday phenomena.

—José Luis Torres Leiva

MA: It’s like a myth being built on the spot.

JLTL: Exactly! That was part of the research: capturing what people told us about their experiences and the events that had occurred in the area. The final structure of the film emerged on location, and each day brought us new surprises and stories. It was incredibly special to feel the film take shape beyond the script. The script was still important, though; all that preparatory work gave us the clarity we needed to approach the project.

Cristóbal Escobar: Watching When Clouds Hide the Shadow, I feel that María blends into the place—its calmness, its people, its pace. It’s a film that, in many ways, teeters between documentary and fiction, and I wanted to know how much of you is real (as in María playing herself) and how much of your connection to the place comes from acting.

MA: The discovery of the place is literally real because I had never been to Puerto Williams before. I’d say the film has an organic sense of time that makes this possible. In Punta Arenas, we had to wait a couple of days for the cargo ship that would eventually take us to the island. When we finally set out for Puerto Williams, the wind was extremely strong. It was a pitch-black night, freezing cold, and the waves were enormous. Everything was dark, and I was a little scared on this small ship that, besides carrying a few passengers, was also transporting nine trucks!

The journey lasted two nights—40 hours we spent talking with a group of anthropologists who were travelling to the island to do an activity with the Yagan community. It was a very natural sense of time, which somehow manifests in the film’s opening scene. Travelling by ship is not the same as taking a plane and arriving in a couple of hours. Crossing the open sea, you see the landscape change, you see the days and nights come and go, and your rhythms adjust to it. We filmed all of that, too. Regarding your question about the character of María, it’s something I ask myself as well. I’d say it’s an intermediate space between acting and presence. At the time, I was also going through grief and felt physically rooted in that place, in the ‘end of the world’ that Puerto Williams represents. The immensity of its nature created a very physical and visceral feeling.

I also have young children, and it was my first time being far from them for so long. That sensation permeated the entire film for me, mixing with the testimonies and real lives of the people who appear on-screen. José Luis was also going through grief, and that’s a theme that touches both of us, not only in this film but in other projects we’ve worked on as directors. I think all of this brought us closer to the story. There was a level of transparency and sensitivity that is not very common in the filmmaking process. I’d even say the final work became this process of searching for the film. The script and the structure were there, but I believe what you see on-screen is profoundly shaped by this shared sentiment.

José Luis filmed the dialogue scenes with two cameras, in real-time, allowing the conversations to unfold naturally. I quickly realised that no scene would be repeated and that everything we were going to do would be unique—captured in a single take. That brings a different weight to the process, more akin to film stock, unlike now where you can shoot for hours with digital cameras. It was an absolute leap into the here and now.

I quickly realised that no scene would be repeated and that everything we were going to do would be unique—captured in a single take. […] It was an absolute leap into the here and now.

—María Alché

JLTL: We talked a lot with the screenwriter, Alejandra Moffat5—who also plays the character of Alejandra in the film—about how to incorporate grief. It’s a deeply personal process where everyone finds their own way of understanding and living it. It’s an experience that shakes your life completely, and you learn to live with the scars left by the deaths of loved ones. In my case, the loss of my mother before the shoot, my friend Rosario Bléfari, and then my father at the end of the film’s production.

In some ways, the movie ends there—when María’s character acknowledges her grief and begins to live through it. The final encounter with the person she takes to the Puerto Williams hospital becomes meaningful for this very reason. It’s a small act with profound value. María decides to wait for her until her examination is done so she can take her back home. She is someone María may never see again, and that speaks to the fragility of life in the face of loss. Once the film premiered, it was very moving to feel how many people shared their own grief with us—stories of family members or friends who had passed away—and how the film had brought them to that emotional place. The same happened with the people of Puerto Williams, who shared their personal stories with us. I’d say that the idea of blending fiction with documentary in the characters we see on-screen is a way of defending lived experience. I believe the film is built on this structure of sharing with others, of listening and being present. It’s a very simple act that, at the same time, becomes complex because it requires an awareness of grief, which is such a real and concrete part of this story.

Cinema is, above all, a human experience that deals with our emotions. The key is to build stories capable of evoking feelings, and all forms of storytelling are valid for that purpose. That’s why When Clouds Hide the Shadow seeks to go beyond mere documentary or fiction. Of course, everyone has their own tastes and preferences, but regardless of genre, I’d say the human element is the driving force behind this story.

Audience Question: How did you approach the staging in When Clouds Hide the Shadow? I’m asking particularly because of the naturalism that the film evokes.

JLTL: I think it was very important to find people who could tell their own stories. I remember that during the initial research, certain stories emerged in our conversations with the island’s inhabitants, which eventually shaped the film’s script. By the time we arrived for the shoot, we already had an idea of the stories they would share. Together with the team, we developed a method to capture those moments as spontaneously as possible.

We recorded each conversation just once, and that dynamic helped a lot to achieve this result. It also allowed us to connect deeply with the reality of these people’s lives and their very intimate stories. For example, the woman in the final car scene is a theatre actress, but she had never done film before. What she tells on-screen is part of her life—the story of her mother, who passed away ten years ago. That was something that still affected her, and that’s why she talks about illness in the film. This was a theme that came up naturally in our conversations and touched me very personally. When she says that if she were to leave this world, it wouldn’t matter much because no one is waiting for her. That felt like a mirror to my own feelings. The fact that she could say this and process her mother’s illness in the way she did was beautiful. She was incredibly generous to share that story in the film because, ultimately, it’s her own. Her mother’s death was a pivotal event that led her to make life-changing decisions.

This was also one of the last scenes we shot, and by the end of the filming, I think there was an accumulation of experiences that allowed María to approach that conversation the way she did. This is the magic of cinema—it makes things work. What happens between María and the woman in the car is a mystery, a conversation that seems to come from the unconscious. I think this is what makes the film so impactful: it’s about how we feel and listen to others, about how someone can be there, accompanying you simply by being close.

MA: A part of this magic in the staging comes from the fact that there isn’t such a big separation between what happens in front of the camera and what happens behind it. All of us were attuned to the same emotional current. But for this magic to happen—especially with people who aren’t actors and who are willing to open up their lives on-screen—there has to be a similar openness from the crew and the director. No one will open up if there isn’t someone on the other side ready to listen.

In that sense, as José Luis said, I think the film is ultimately a human experience: directing is about giving someone the opportunity to share themselves, to open up with trust in front of the camera.

When Clouds Hide the Shadow will be screened on Saturday, June 7, as part of the BBBC Symposium Coming to the Edge, organised by Jake Wilson, Philippa Hawker, and Cristóbal Escobar at Gallery Gallery Inc.

**********

Cristóbal Escobar is a Lecturer in Screen Studies at the University of Melbourne and a Film Programmer at the Santiago International Documentary Film Festival (FIDOCS). His publications include The Intensive-Image in Deleuze’s Film-Philosophy (Edinburgh UP, 2023), an edited collection on Cine Cartográfico (La Fuga Ediciones, 2017), and a forthcoming second volume with Barbara Creed on Film and the Nonhuman (University of Exeter Press, 2026). His current research focuses on the concept of mestizaje in contemporary Latin American cinema.

- José Luis Torres Leiva (Santiago, 1975) is a director, screenwriter, and editor. His films include: No Place Nowhere (2004); The Sky, the Earth and the Rain (2008), which won the International Federation of Film Critics (FIPRESCI) award; Verano (2011), which premiered at the Venice Film Festival; The Wind Knows That I’m Coming Back Home (2016); Death Will Come and Shall Have Your Eyes (2019); and When Clouds Hide the Shadow (2024). ↩︎

- María Alché is a director, scriptwriter, and actress, who starred in The Holy Girl (2004) by Lucrecia Martel. Her first feature film A Family Submerged (2018) premiered in Filmmakers of the Present at Locarno Film Festival 2018 and won the Horizons Award at San Sebastián International Film Festival 2018, Best Screenplay at Lima Latin American Film Festival 2019, Ingmar Bergman International Debut Award at Gothenburg Film Festival 2019, Critics’ Award at Barcelona D’A Film Festival 2019, and Best Director at FICUNAM International Cinema Festival 2019, among others. ↩︎

- In the early 1980s, a couple vanished without a trace in the woods of Meulín Island. Director Ignacio Agüero had intended to shoot a documentary about this strange occurrence, but eventually abandoned the project. Now, he journeys to the area to shoot his first fiction film based on the events, and Torres Leiva follows Agüero as he speaks with locals about the legends that have arisen surrounding this mysterious occurrence in between scouting for locations and auditioning nonprofessionals, who often provide a source of tender comic relief. The film is also a meditation on the isolation of those living on Chile’s Chiloé Archipelago, capturing its unique and solitary landscapes. ↩︎

- Tiziana Panizza Montanari (Santiago, 1972) is a Chilean documentary filmmaker, television producer, researcher, and teacher. Her works include the Visual Letters trilogy Cartas Visuales (2008), Remitente: A Visual Letter (2008), and In the End: The Last Letter (2013). Her latest film, Tierra Sola (2017), premiered at Visions du Réel and has garnered over a dozen international awards. ↩︎

- Alejandra Moffat (Chile, 1982) is a writer and screenwriter. She co-wrote 1976 (2022) by Manuela Martelli, The Wolf House (2018) and The Hyperboreans (2024) by Joaquín Cociña and Cristóbal León, Antitropical by Camila José Donoso, and All the Letters I Never Sent (2017) by José Luis Torres Leiva, among others. Her publications include the novels MAMBO (2022) and The Bedmaker (2011). Her short stories have appeared in anthologies such as Living Over There (2017), Let Me Know When You Arrive (2019), and Nothing (2019). She is the scriptwriter of When Clouds Hide the Shadow (2024). ↩︎