Oh, Canada is a whiskey-neat piece of work, a real strong and silent type. The film is based on late author Russell Banks’ 2021 novel Foregone, and marks the second time his work has been adapted by close friend Paul Schrader, the first being the 1997 neo-noir Affliction. The drama concerns Leonard Fife, a Vietnam War draft-dodger who sought refuge in Canada, where he became an acclaimed political documentarian. In present day 2023, the now-dying man (Richard Gere) recounts his story for a final interview conducted by his former filmmaking students.

The film opens with past student Malcolm (Michael Imperioli) clad in black glasses so large they rival Milton Berle’s, dragging camera equipment through the incredibly lush, wood-panelled dining room of Leonard’s apartment. A decadent chandelier and candle fixtures are supplemented with studio lighting brought in by fellow student Diana (Victoria Hill) and young assistant Sloan (Penelope Mitchell).

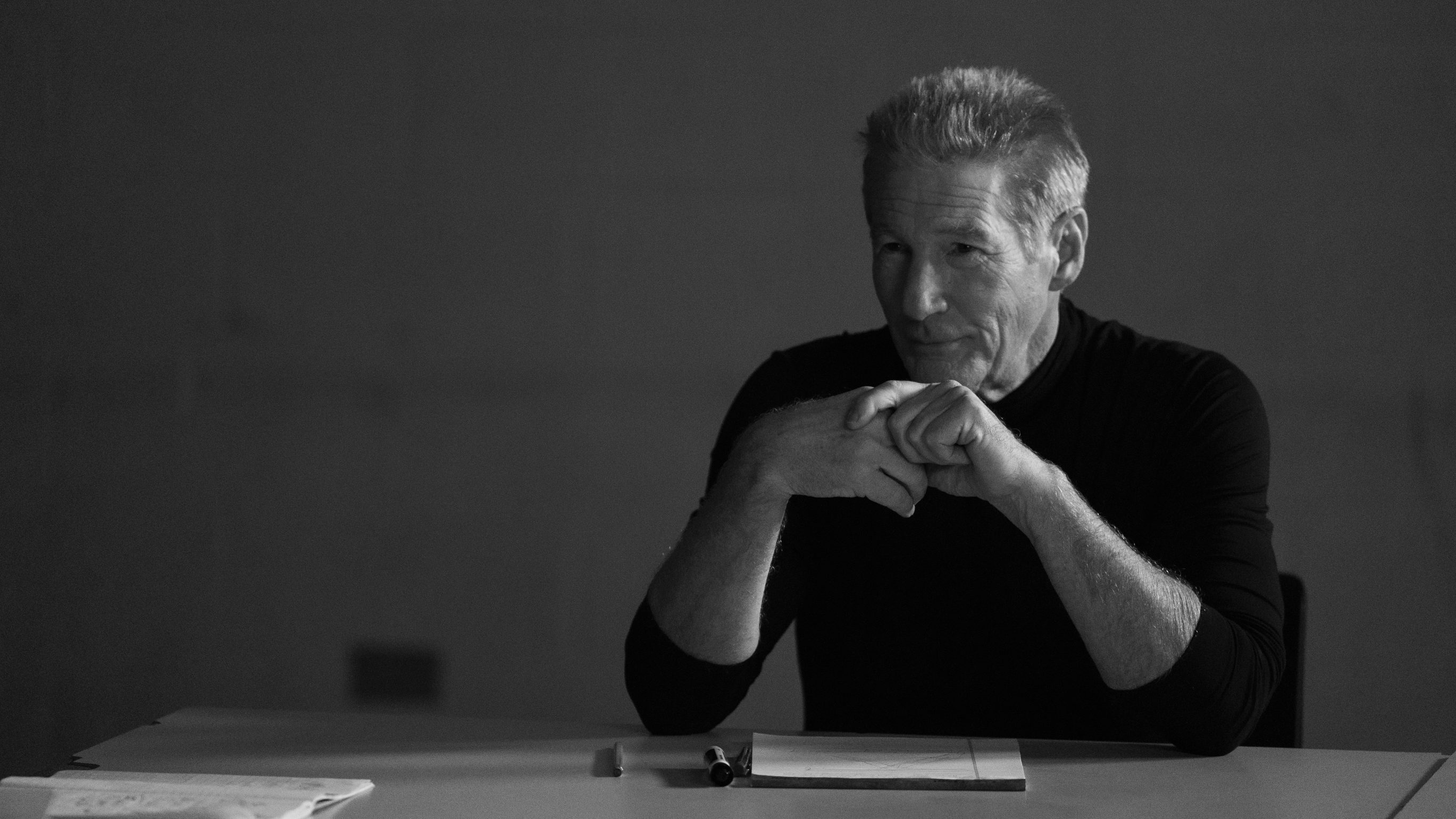

Enter Gere as the film’s discombobulated, sickly anti-hero. His presence is a far cry indeed from the svelte pretty boy we met four decades ago in Gere and Schrader’s last collaboration, American Gigolo (1980). His luscious locks are reduced to a few meagre tufts of white straw, and inconsistent sprigs of stubble line his pallid face. Leonard’s wife—another former student turned producing partner, Emma (Uma Thurman)—brushes a perfunctory powdering of foundation across his face. Malcolm coughs up a mock compliment: “You look great.” No one is as aware as Leonard, who quips, “Never looked better.”

The film darts between colour and black-and-white, with varying aspect ratios, across Leonard’s past and present, where he endeavours to give a truthful account of his life. He commands Emma to remain by his side so he may more comfortably regale the camera with his life story, treating the lens as a priest and the makeshift studio as a confessional. Leonard looks the camera square in the eye: “The story begins with the night of March 30th, 1968, Richmond Virginia…”

Enter Jacob Elordi. This strapping young gentleman is fabulously cast as Gere’s younger counterpart; both have a similarly wonderful, engrossing charm—you half-expect them to help an old lady cross the road, or drape their suit jacket over a puddle for a pretty pedestrian in distress, though this allure belongs to a less-than-gallant character. Gere intermittently steps in, too, to play a livelier Leonard in his own memories, giving the audience a moment’s reprieve from seeing the powerhouse haggard and hollow-eyed. This creative tactic represents Leonard’s attempts to plunge himself back into the past and tell the truth as he finds it: a technique employed thoughtfully at times, verging on woefully uncomfortable at others.

In a recollection of his tender early twenties, Leonard reads a story to his newborn child and rests his head on his wife’s baby belly. A scene later—switch—Gere swaggers into the room, full of life. Uh oh. He’s rubbing her belly rather intimately. She’s nuzzling into his face. Focus on the gorgeous peignoir, focus on the peignoir.

Leonard also spares no detail of his philandering; I had trouble keeping count of the women he romanced and the children he fathered. We must consider his deteriorating state—are these amorous accounts truthful, or the inventions of a man who struggles to part fact from fiction? Emma is distraught to hear of his adultery, and insists it’s an invention of his ailing mind. The viewer is swept up in this intriguing minefield of memory and infidelity, left unsure whether these are the cries of a wife in denial, or if credence should be given to her words.

The flashbacks progressively plunge further into the uncanny valley, as actors play several roles, or play their characters several decades younger. In the 80s, Leonard is a lecturer, educating the students that now surround him in the present day. Emma dons an effortless side pony and an oversized denim jacket, and Malcolm models slick, jet black hair. Thus marks the juicy apex of the film, where time is finally dedicated to exploring the students’ past, and how Leonard played into it. Little interpersonal dramas take centre stage, and Oh, Canada becomes deliciously gasp-worthy.

The film’s oscillation between visual styles, and the clever, psychologically-driven placement of the core actors, make the viewer feel as disoriented as our lead. Schrader paints a portrait of a man grappling with his past wrongs as a lover and a father, seeking absolution through confession as he stubbornly attempts to preserve a mind that fights against itself. Yet, off the heels of his widely acclaimed thematic trilogy (First Reformed [2017], The Card Counter [2021], and Master Gardener [2022]), a series of celluloid slow burns in which the leading men steep in guilt, regret, and reckonings with their pasts, Oh, Canada feels largely unremarkable. The preceding films swell with the weight of their characters’ histories, while Oh, Canada maintains a fuzzy distance that aerates Leonard’s narrative.

Schrader’s choice to focus the film on the memory of a fading man, though immersive and effective, is the very thing that works against it, diluting the dynamics of his personal relationships. There’s a lack of humanity and tenderness between its subjects that leaves you unmoved. A considerable amount of time is dedicated to Leonard’s romantic entanglements; he shares moments of physical tenderness with female partners and discusses his self-perceived inability to love, but these relationships are glossed over, largely unexplored. We sleepwalk through the hazy benchmarks of his life without so much as a pit stop. The struggling Leonard cuts through memories, desperate to air out his shortcomings, yet remains disinterested in lingering on the nuances that might add dimension to his character. Leonard’s determination to convey his coldness, to dispel notions of his goodness, water down Oh, Canada. It becomes the kind of movie you see at 10am on a Tuesday, with just a stray elderly couple populating the seats, because you had nothing better to do. Or the kind of thing you half watch on SBS on a sleepy Sunday afternoon.

At the midpoint of the film, Leonard blesses us with a great monologue:

“I made a career getting truth out of people that told me what they wouldn’t tell others, now it’s my turn…. This is my final prayer, and whether or not you believe in God, you don’t lie when you pray.”

Behind the cool grate of a confessional, you are direct and ashamed, telling the priest only of wrongdoings and elemental truths. When you kneel in prayer, you are humble and self-effacing, careful not to inflame a God who disdains pride. Yet in his desperation to set the record straight, Leonard also sacrifices sensitivity, nuance, and distinction. To him I say, honey, a little white lie never hurt anybody!

Oh, Canada is in Australian cinemas now.

**********

Mia Quartermaine is a queer writer and DJ based in Perth/Boorloo, with a particular affinity for film and culture. Her reviews have been published in Magazine600.