Voice acting in video games is a risky proposition. With the sprawling open-world fantasy role-playing game The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion (2006), Bethesda Game Studios made the decision to fully voice its in-game dialogue, pivoting away from the text-heavy, PC-centric design of its predecessor, The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind (2002). This spatially larger, more ‘cinematic’ vision was tailored toward a new generation of consoles whose capabilities were not yet fully understood. Recording the game’s dialogue was a vast undertaking that resulted in a sound archive exceeding 200,000 words—a record that, four years later, the studio would top with Fallout: New Vegas (2010).

Oblivion‘s non-playable characters (NPCs) are well-known as the source of some of video game history’s funniest ‘fails.’ Hammy acting, stilted writing, and intense camera zooms abound; not to mention glitches in physics, tonally odd conversations, and jarring irregularities of AI behaviour. As YouTube attests, timing can be serendipitous. ‘Mages Guild Well’ shows a party of allies struggling after following the player into a well to their watery deaths, with one member reanimating at the video’s end in an accidental jump-scare close-up delivered directly to camera, urging us, “I hope we’ll get to Skingrad soon.”

A compounding factor at play in moments such as these is Oblivion’s innovative Radiant AI system, designed to allow NPCs to systematically interact with the world around them without the need to individually script actions by human hand. These mechanics can be seen in action in ‘Farewell.’ Here, a quest-giver cheerily addresses the player, only to be crushed to death the next moment by a triggered stone trap; unscripted, a friendly knight approaches from offscreen to pay his respects; seconds later, he meets the same unfortunate fate. Silly, yes. However, whether these janky joys are best described as ‘failures’ is something we might question—provided we consider Oblivion’s value not as the dignified Lord of the Rings tribute intended, but as an engine for absurd, dream-like moments its creators didn’t fully anticipate.

On top of the technicalities of programming and AI design in games, there are special challenges voice actors face in grounding their performances. In many directorial practices (Oblivion being an easy-to-tell case), actors are brought into a recording booth without prior knowledge of the script, where they read for hours at a time, facing the tonal whiplash of working through lines in a non-linear fashion. This makes for a marked contrast to stage acting, where character arcs can be modulated linearly, bouncing off the live energy of both castmates and audience members.

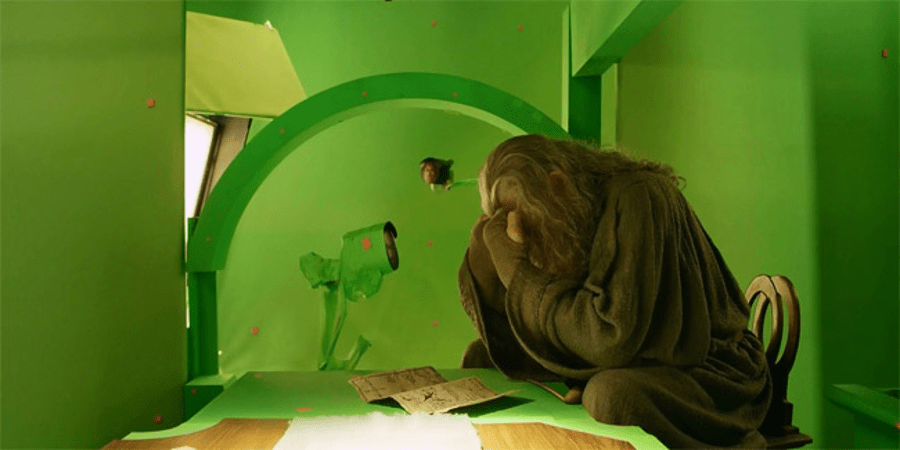

In interviews, Oblivion’s Wes Johnson has likened the booth experience to being dropped into the ocean in a diving bell, while fellow cast member Elisabeth Noone related the restraint needed to avoid knocking over the sound engineer’s gear: “You have to learn how to control your hands, for God’s sake!” The best booth actors are those capable of conjuring an elastic improvisatory flair, but not everyone makes the transition to cramped conditions happily. Shakespearean orator-turned-pop-celebrity Ian McKellen once recounted breaking into tears while filming with a green screen for The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012), strained by the effort of having to pretend he was with other people—alone, surrounded by thirteen photographs of dwarves attached to stands.

Since the days of Oblivion, expectations of polish for games at scales both large and small have skyrocketed. The dominant style of acting that has emerged is hyper-articulated, controlled, broad, and emotive. In the commercial sphere, General American and Received Pronunciation voices are dominant, and it’s not uncommon for non-Anglo studios courting international markets to hire English-speaking natives, regardless of the game’s setting. The overall effect is a constructed reality of sorts: a placeless, global aesthetic. Artificiality may be part and parcel of video games’ affordances as a form, but this particular flavour seems not so much strange and otherworldly but of a familiar kind already pervasive in the world—that of advertising logic. For games with ambitions to break outside of the self-referential world of pop culture tropes, there’s a further problem: an aesthetic that strips itself of local, ethnic, or cultural markers is likely to also sacrifice meaningful connection to recognisable, lived experience.

*

Turning to film history is instructive when looking for performance styles that disavow conventional notions of quality. In many cases, a fresh idiosyncrasy has been introduced by the performances of non-professionals: the adaptable Inuit hero of Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1922); the class-appropriate non-stars of Sergei Eisenstein; the wary fishermen who play off Ingrid Bergman’s glamour in Roberto Rossellini’s Stromboli (1950); or the camped-out, ultra-eccentric Superstars of Andy Warhol’s Factory. These figures may be included to achieve a sense of documentary realism, or to challenge conventions. Robert Bresson’s use of non-actors was an attempt to move away from film acting’s imitation of theatre—which for him was like a photograph of a painting, devoid of the original’s power.1 He aimed instead to allow the camera to spontaneously catch the model’s own being, rather than the studied movements of a trained professional: “I want the essence of my films to be not the words my people say or even the gestures they perform, but what these words and gestures provoke in them.”2 There are few performances as movingly awkward as that given by Nadine Nortier as a French peasant girl in Bresson’s Mouchette (1967), obstinate and wounded at once, scowling sadly as she clops around in dowdy pigtails, ensnared in the cruelties of village life.

This brings up the question of what could count as ‘gesture’ in video games. A traditional limitation is that characters are usually not embodied by actors, but animated painstakingly by technicians—we might imagine Bresson’s terror of theatrical self-consciousness amplified a hundredfold. The resulting performance could be seen as collaborative puppetry: the voice actor playing ventriloquist to the animator’s dummy. In other cases, rotoscoping animation has been used effectively to imprint a person’s bodily movement within a game. Pixel horror game Faith (2017) creates a brief, truly uncanny effect by cutting to a rotoscoped animated image of demonic entities at key moments. Detective puzzler The Last Express (1998) uses the 2D technique beautifully in a real-time, 3D perspective, with characters approaching and shuffling past you in a squeezed compartment coach. Their movements are surprisingly natural; there’s a palpable impression of interloping in an embodied world—not merely a simulated one—that exists independently of the player’s arrival. The development of motion-capture performance technology further bridges the gap between word and gesture. Far Cry 3 (2012) flaunts its technological feat by having its villain emote wildly in a full-bodied performance, crouching down and leaning into the player’s face, invading their personal space.

Reputedly ‘bad’ examples of acting craft sometimes prove to be the most interesting examples of it. For cost-saving and convenience, it was once common for voice acting to be performed by members of the development team, as it was in Looking Glass Studio’s System Shock (1993) and System Shock 2 (1999). In the Shock series, the nameless hacker protagonist explores a space station, collecting audio logs left behind by dead crew members—miniature radio dramas, which allow the player to piece together their unfortunate fates. This nerdy, inexperienced cast lend an unrehearsed vulnerability to the characters; as with Nortier in Mouchette, the awkwardness is a boon. With mixed levels of charisma, the characters convey the passive-aggressive bickering of the ship’s workers—even before the horrors broke out, it seems this place was a low-key hell. The resulting style is one that feels appropriate to the subject matter: ordinary people caught in desperate situations.

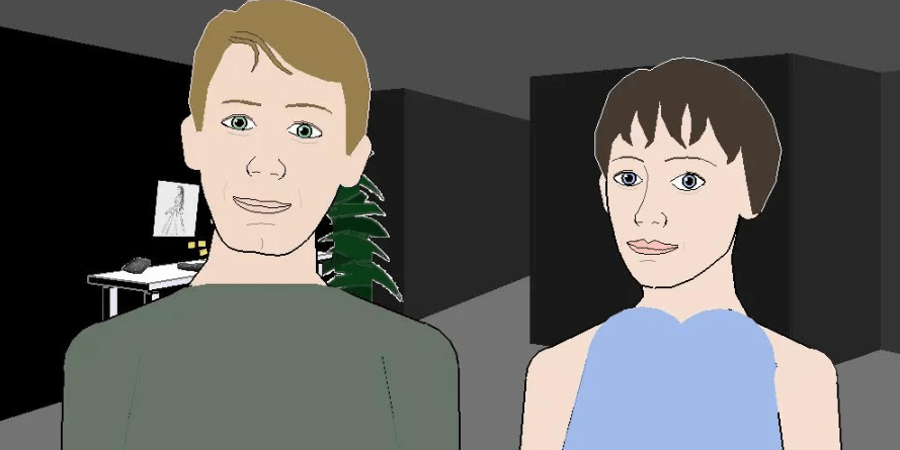

Meanwhile, in Façade (2006), an elasticity of performance is achieved not by the actor or in the method of capture, but by the programmer-writer-designers. A unique experiment of performance in games, the plot is loosely based on Edward Albee’s play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf: a bourgeois couple, Grace and Trip, have invited the player to their apartment. You are then tasked with saving their ailing relationship, which falls apart in front of your eyes. The player can type their own dialogue, to which the game reacts via natural language processing. While similar conversation points will be hit on repeated playthroughs, the two NPCs are not hard-coded to have specific directions at a given time. The rhythm of Grace and Trip’s speech is modulated according to the player’s words and actions, as well as their apparent feelings about certain topics. They can be interrupted mid-sentence and will adjust dynamically. They pause for responses, sigh frustratedly at each other, mutter to themselves, fill silences with “umms,” laugh awkwardly, talk over one another, and so on. I can’t think of a game that has such detail in spoken speech.

The messiness of Façade flies in the face of the convention of contemporary games, where there tends to be a focus on clarity. The developers are keen to make sure no piece of information is missed by the player. One wonders what a game could look like without this emphasis. In the films of Robert Altman (M*A*S*H [1970], Nashville [1975], California Split [1974]), we often hear multiple lines of dialogue overlapping, without one being emphasised over another. The viewer must pick their own stresses and lines of entry, scanning the screen for points of interest. A group of video games that hint towards this territory are the most recent iterations of stealth sandbox Hitman (2016-2021). These games task the player with assassinating a number of targets, offering a multitude of approaches for traversing the level and dispatching them. There is ample NPC chatter in its densely populated spaces: sometimes clues that pertain to your task, other times simply amusing—or inane—mumblings. Entering an area and eavesdropping on its murky speech is a thrill, which offers a sense of possibility and multilinear adventure.

*

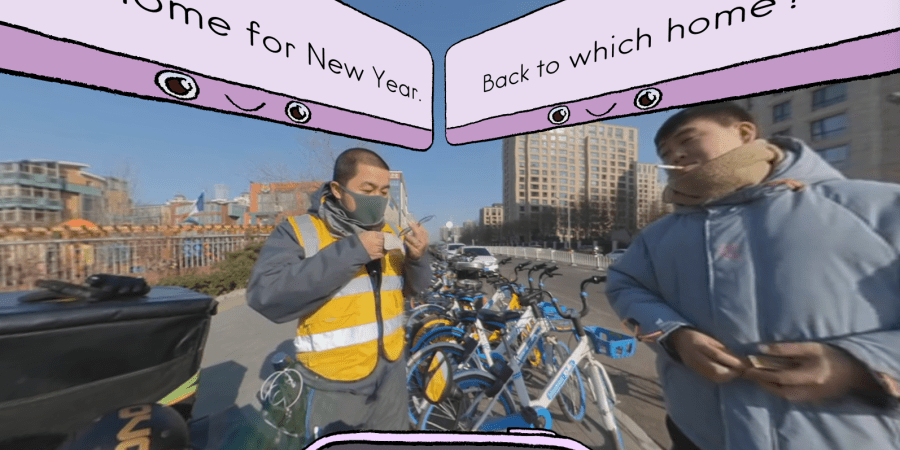

“Playable documentary” Out For Delivery (2020) is a 42 minute 360-degree video depicting food delivery workers in Beijing the day Wuhan City shut down due to COVID-19. The player sees the city and inhabitants in first-person from a fixed point—the camera held by Yuxin Gao, the documentary’s creator—and follows the workers on foot and scooter. The player can change the direction of the view by moving their mouse, in a similar manner to a first-person shooter. The actors in this game are simply documentary subjects, living their lives, going about their ordinary jobs. Artist and game developer Robert Yang, whose article “A call for video game realism” inspired Out For Delivery’s creation, has described the game as an “alienation simulator,” for what it might reveal to someone from the West about what they don’t know about contemporary China. In another sense, the method of its creation produces one of the least alienated gaming experiences I can remember, a counterpoint to one of the central characteristics of video games, and nerd culture generally: estrangement from the lived, practical world.

**********

Austin Lancaster is a screen critic and learning support officer with bylines at Rough Cut, KinoTopia, Senses of Cinema, and Rock Paper Shotgun. A versatile writer, he likes to take up perspectives that cross boundaries between different art forms, with particular interests in indie games, world cinema, and philosophy. His latest writing can be found at his newsletter, ‘Umby Cord’.