The 2024 Melbourne Queer Film Festival delivered another queer classic with City of Lost Souls, and it was one I was long overdue to see—both as a trans person and as a German. Rosa von Praunheim’s film, a shrill, musical parody of 1980s Berlin, was considered avant-garde when it first premiered. It remains so today—not because the world has progressed beyond its provocations, but because it captures ongoing discourses that matter to the trans community, as well as a seeming clash between the camp, migrant, transsexuals in this film and their post-war German environment.

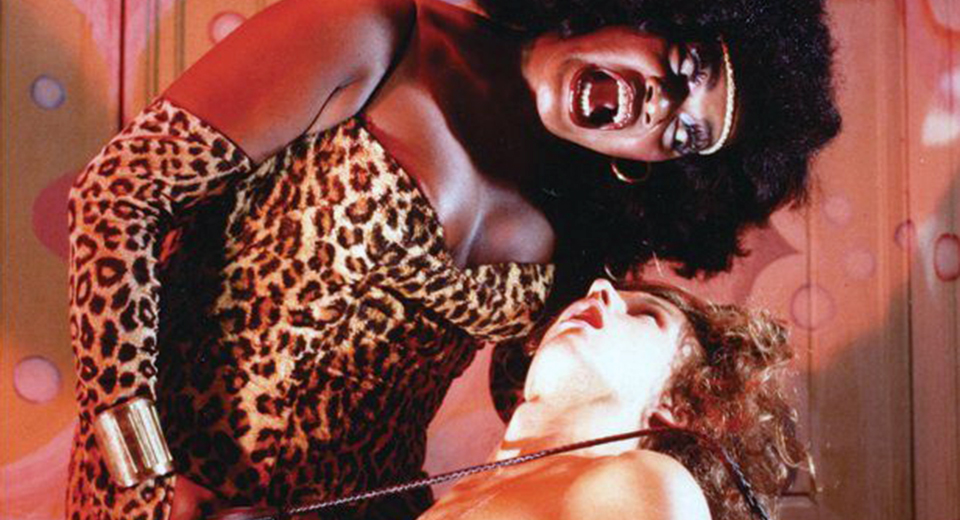

At the heart of City of Lost Souls are trans actresses Jayne County (Lila) and Angie Stardust (as a character of the same name), leading an eclectic ensemble of misfits within a plot that is mostly hard to discern. Angie runs a boarding house, Pension Stardust, inhabited by a cast of outsiders: an erotic trapeze duo, a mystical group therapist, various nymphomaniacs, and Lila, a Southern blonde with Hollywood dreams. Their days are spent working at Angie’s fast food joint, Burger Queen. But when Lila gets pregnant by a Communist promising her fame on East German television, chaos ensues.

Often described as Hedwig and the Angry Inch in reverse, City of Lost Souls follows American trans and queer artists arriving in Berlin, disrupting its rigid social norms with their flamboyant excess. Where Hedwig tells the melancholic tale of a trans rock musician fleeing East Berlin in search of freedom, City of Lost Souls refuses the tragedy, embracing camp, parody, and a radical rejection of respectability.

In City of Lost Souls, von Praunheim dares to be optimistic, a stance that unsettles cultural inclinations in Germany, then and now, 40 years later. Leaning into the polemic, I would call this a distinctly German fatalism—a cultural tendency to accept suffering, hardship, and historical trauma as not only inescapable but, at times, even necessary. It is a mindset that turns resignation into virtue, pain into proof of endurance, and joy into something suspect. It manifests in various ways, including a deep-seated attachment to guilt, discipline, and pragmatism, often expressed through phrases like “Muss ja” (literally “Must, yes,” meaning “It has to be done” or “There’s no other choice”).

This outlook can foster a resistance to optimism and a scepticism toward utopian visions such as those that the director has put forward since his first film, It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives (Nicht der Homosexuelle ist pervers, sondern die Situation, in der er lebt, 1971). From this film onwards, von Praunheim has exposed conformity, gay or straight, and political apathy in West Germany, calling for a radical restructuring of queer life rather than assimilation into heterosexual, bourgeois norms. It is this commitment among others that has earned him the title ‘Pope of the Gays,’ as his films have sparked important ongoing debates, helping to catalyse LGBTQ+ activism in the country. City of Lost Souls is no exception in this regard.

The film’s main characters each embody a specific German cultural anxiety, affected by the East-West divide and the very much ongoing racism and Nazism in the country. Lila’s Hollywood aspirations are framed as both admirable and farcical, and her pregnancy—an ultimate disruption of gendered expectations—becomes the film’s absurdist climax. Her decision to move East for her Communist lover also plays with Cold War anxieties about cultural ‘contamination.’ Meanwhile, Angie, as both a Black and trans woman, is already an anomaly in Germany’s overwhelmingly white and cisnormative cinematic landscape. By playing a version of herself, she blurs the lines between fiction and reality while embodying the matriarch who provides an alternative economy of care and community outside of Berlin’s alienating and racist structures.

A key exchange unfolds between Angie and one of her tenants, Tara O’Hara (also playing herself). Angie, who identifies as a “transsexual” and wishes to undergo surgery, finds herself challenged by Tara, a “transvestite” who insists that trans women belong to a “Third Sex” and that surgery is no longer necessary to be a “real” woman. In fact, she sees it as outdated, even foolish, to believe that a procedure could define one’s womanhood. A generational divide emerges: Tara dismisses the desire for surgery as “old school,” which provokes Angie to push back, telling her to hush and listen: “Because of the ‘old school’—because of us—you can be what you are.”

This exchange aligns with ongoing debates about trans validity, dysphoria, and the place of medical transition in trans lives. It raises critical questions about trans materiality and the paradox of defending bodily autonomy while desiring change for oneself. Their conversation acts as a reminder that no single trans person can be expected to carry the advancement of transgender politics on their shoulders, let alone perform these politics on their own body by forgoing life-saving medical care. This tension—between the need to justify transition and the pressure to transcend it—continue to define trans discourse today. At the same time, the exchange speaks to the importance of remembering those who came before us, not merely as a gesture but as an active engagement with embodied trans history. This theme has surfaced in recent cultural works, such as A Language of Limbs (2024) by Australian novelist Dylin Hardcastle or Netflix’s documentary Outstanding (2024), which explores the history of LGBTQ+ comedy through figures like Lily Tomlin, Eddie Izzard, and Sandra Bernhard.

At its core, City of Lost Souls refuses moralising discourses around trans identity. It does not plead for legitimacy within existing gender frameworks. It does not insist that gender exists as a simple binary to be either upheld or abolished. Instead, it revels in transsexuality as a site of contradiction, excess, and joyful rejection. As Black trans scholar Marquis Bey argues, “the assertion of a legible gender at times acts as a coerced capitulation that forecloses a radical alternative possibility of subjectivity in the refusal of gender, of gender abolition.”1 City of Lost Souls resists this capitulation: the film celebrates trans freakish-ness and othered status. Until the end, it prioritises this celebration, showing the characters dancing and singing at Burger Queen, sparking a desire to be a part of their posse, while leaving the on-screen Germans outside looking in.

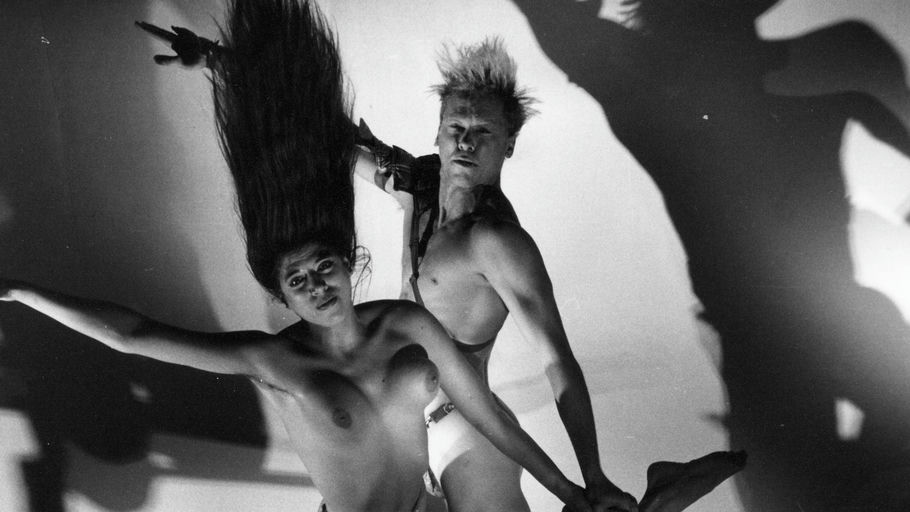

Throughout the film, German onlookers gaze at the trans foreigners with a mix of fascination and disdain—marking the clash between trans exuberance and German conservatism which persists to this day. Von Praunheim’s work consistently critiques this national conservatism and, as I put it, a sense of cheerlessness, which he seeks to counter through parody and subversion. In other words, City of Lost Souls is a film that Germany desperately needs—a transsexual spectacle packed with optimism and an irreverent teasing of the petit bourgeois. It unsettles German fatalism and conservatism as von Praunheim understands it. The trans characters are happy-go-lucky, optimistic, and self-made—not in the grim, world-weary way that might make them palatable, but in a way that defies Germany’s fetish for struggle.

In the film, transness and Germanness appear almost antagonistic to one another. This tension is heightened by the fact that the trans women at its centre are not German but American creatives, a deliberate contrast to the sullen, repressed heterosexuals who shun them. Yet von Praunheim’s vision is clear: these trans foreigners, in all their excess and exuberance, are the ones who are truly alive. City of Lost Souls not only portrays trans life as a site of joyful defiance but also situates it within a broader critique of German social structures, drawing a link between joy-deprived post-war Germany and the possibility of what von Praunheim has called a “pleasurable utopia.”2 City of Lost Souls imagines Berlin as a nightmare for the German petit bourgeois: filthy, racy, deviant, transsexual, while celebrating the freakish and fabulous American creatives who ‘overrun’ the city.

Von Praunheim’s career has been a challenge to the country’s rigid social and moral structures, shaped in no small part by the legacy of its fascist past (as well as its fascist present, which he perhaps anticipated). Born Holger Radtke in Nazi-occupied Latvia (1942), von Praunheim chose ‘Rosa’ as a deliberate act of remembrance and resistance, as ‘Rosa’ serves as a constant reminder of the pink triangle that the Nazis forced gay prisoners to wear—a symbol of persecution, provocatively reclaimed.

In today’s political climate, with the resurgence of fascist rhetoric in Germany and beyond, his gesture feels more urgent than ever. As reactionary forces seek to roll back queer and trans rights, von Praunheim’s lifelong defiance stands as both a warning and an insistence that LGBTQ+ histories, resistance, and lives must not be forgotten, but venerated. City of Lost Souls is not just a cult classic—grappling here with my own brand of German fatalism—it is a vision of trans joy that remains radical precisely because the world is increasingly hostile to it. In resisting tragedy as the defining narrative of trans life, von Praunheim and his cast offer something that still feels dangerous: the possibility that transness is not just a site of struggle, but of pleasure and defiance.

- Feminism against Cisness, 2024, p. 159. ↩︎

- In a 1983 interview withWOZ Die Wochenzeitung, von Praunheim says: “This desire to suffer is also something typically German, romantic. In many situations, I simply wish for a little bit of utopia, a pleasurable utopia” (translated into English by the author). ↩︎

**********

Claude Kempen is a white and trans nonbinary writer from Berlin, currently pursuing a PhD at the Universities of Melbourne and Potsdam. Their research focuses on contemporary nonbinary memoirs, with the aim of developing a nonbinary theory. Their previous academic work has examined Islamophobia in pornography (ZMO Working Papers, 2020), queer activism in Jordan (De Gruyter 2021), and medical gatekeeping in German trans healthcare (Routledge, forthcoming). Claude’s nonfiction writing has addressed grief and transgender spirituality (AnthroDesires, 2021) and the trauma of surviving coercive and corrective surgery during childhood (Archer Magazine, 2024).