Early in his career, the now-iconic British filmmaker Mike Leigh developed a unique preparation method geared towards lucidly capturing the concerns of the present moment. Informed by his education and work in theatre in the 1960s, and first manifesting through his prolific television output in the 1970s, today Leigh continues to create characters and scenes in direct collaboration with his casts during months of extensive rehearsals and improvisations, eventually solidifying their work into a precise script before the cameras roll. Though often lauded, Leigh’s method is one of cinema’s most misunderstood; he still fields questions at film festival Q&As about how much improvising takes place in-front of the camera, or whether these films have scripts at all.

Longtime viewers of Leigh’s work might find audiences’ continued confusion odd, as his scripts, tightly calibrated and carefully dramatised, are obviously set apart from the loose, in-the-moment energy of known cinematic improvisors like Howard Hawks, John Cassavetes, and Jacques Rivette. Instead, Leigh seems to see improvisation as an uninhibited process of channeling contemporary issues and the characteristics of “real people.” The tone of the resulting films has more in common with kitchen sink realism than avant-garde theatre—albeit an eccentric and colourful realism that emerges from the lived-in experientiality he and his casts build together.

After tackling contemporary issues through historical settings in Mr Turner (2014) and Peterloo (2018), Hard Truths returns the director to present-day London, exploring the life of Pansy (Secrets & Lies [1996] star Marianne Jean-Baptiste), an abrasive and anxious housewife, and her extended family of Jamaican background: her disengaged plumber husband Curtley (David Webber), unemployed adult son Moses (Tuwaine Barrett), hairdresser sister Chantelle (Michele Austin), and young professional nieces Kayla (Ani Nelson) and Aleisha (Sophia Brown). Despite being forced to work on a smaller budget, the infallibility of Leigh’s process quickly presents itself in the complexity of Pansy, whose unrelentingly critical and darkly humorous treatment of people is examined—and eventually unravelled—with a subtle, unexpected humanism.

Note: the following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Andréas Giannopoulos: When presenting Hard Truths at the New York Film Festival you mentioned that the film had an improvisation and rehearsal period of 14 weeks due to budgetary constraints, which is very short for you. Did that affect your usual way of working with actors towards a script?

Mike Leigh: Not at all. Not one bit. It just meant that there were less complexities in the narrative. And indeed, there’s quite a small cast, but in terms of the way we worked, it absolutely was not affected by it at all. You can’t cut corners. You either work in that way, or you don’t.

AG: Did yourself and the cast feel rushed at all by the shorter period?

ML: No, you just get on with it. The point about all art is that you cut your cloth according to its length.

AG: Did part of this preparation period take place within the locations, before the crew was involved?

ML: We don’t go on-set until we get to the shoot. The 14 weeks preparation is in an empty building, just creating the world of the characters and the premise of the film. Then there’s a six-week shoot, during which we shoot the film. A part of shooting the film is to go, location by location, sequence by sequence, working without the crew, and build each scene with the actors as we go, my having worked out a provisional structure that is drawn from my imagination and what we’ve been doing in the 14 weeks. The crew comes back. We look at it. We shoot the scene, the crew goes away again, we have a rehearsal day or two days or whatever it is, we make another scene, and that’s how it works.

AG: You’ve said previously that you struggled to get financing for Hard Truths. Is it getting harder to make your kind of film?

ML: Absolutely. Much harder. It’s hard to get backing for independent movies, anyway. By independent, I mean films that aren’t interfered with by streaming services or executives who want you to change the cast, or change the ending, or use AI or algorithms to work out what audiences want, and all that shit.

It’s harder still for me, because all I can say to a backer is: “There isn’t a script. I can’t tell you what it’s about. Can’t discuss casting. And please don’t interfere with us while we’re making the film.” And a portion of them are positive about it, but the majority of them don’t want to know. Some people say, “Well, we love what you do. We appreciate your work, we respect you, blah, blah, blah, blah. But it’s not for us.” And “Not for us” is code for, “We can’t get involved in anything that we can’t interfere with and generally fuck up.”

AG: Does the way the industry is trending towards this mentality worry you as a filmmaker?

ML: Yes, it worries me as a filmmaker, but more than that, it worries me on behalf of young filmmakers and films of the future. I’ve already made 27 films. But I worry about young filmmakers—indeed filmmakers that may not have been born yet—not being able to make movies with the freedom with which other artists paint pictures, write novels, write plays, write poetry, make music, and make sculpture, et cetera, where you really don’t get interfered with at all, you just follow your instincts and do it.

AG: The last contemporary-set film you made was Another Year (2010), about 15 years ago. When making Hard Truths, was your approach changed by any developments since then in the modern world?

ML: I mean, I’m in the modern world, and the modern world is the world you’re in at any given moment that you’re in it. It’s not as if I’ve been hiding in the 19th century, or that I personally have actually been in the 19th century whilst I’ve been making [Mr Turner and Peterloo]. I was here in the 21st century. I’ve been through all the things that we’ve all been through. So I’m tuned-in, you know? The short answer is: not at all, no.

Quite a lot of people have said, oh, [Hard Truths] is obviously a post-pandemic film. Well, it is a post-pandemic film. It’s set in the 2020s and therefore, by definition, it’s a post-pandemic film. But really, there’s nothing inherent in what the film is actually about that is specifically post-pandemic: the issues, and the characters’ behaviours, and the crises, and the psychological conditions, and all the rest of it. We could have made the film ten, 20, or 30 years ago, in that sense. But obviously the milieu, the timbre of time and place, is ‘now.’

AG: Do you think people are relating Pansy’s characteristics of being a hypochondriac and germaphobe to the pandemic?

ML: Some people are. I think it’s a red herring, quite honestly.

Why is that?

ML: Well, because I think it’s irrelevant. I can’t say any more than that. It’s a condition. People say, “Oh, well, she would have been locked indoors during the pandemic.” Well, she’s locked indoors anyway. That’s part of her condition.

AG: There are quite a few actors in Hard Truths that you’re working with for the first time, with the notable exceptions of Marianne Jean-Baptiste and Michele Austin. You’ve said that in general you look for character actors, but in addition to that, what is it that draws you to a particular actor?

ML: I only work with character actors because only character actors can do my stuff, which is, they don’t just play themselves, but are good at doing real people out there in the street. Obviously I’m not interested in actors who are ‘personality’ actors, who project themselves. That’s not of any interest to me at all. It’s not practically useful.

AG: You often work with the same heads of department on multiple films. What do you look for in your creative collaborators?

ML: The point is, you’re either on the same wavelength, or you’re not. I don’t work with anybody that hasn’t got a sense of humour, that hasn’t got a grounded sense of commitment to making films about the real world, and that isn’t highly sophisticated in their craft. So, whether it’s the designer, the cinematographer, the costume designer, or indeed the actors, it’s all about being serious and committed to depicting and exploring the real world in a sophisticated and distilled and artistic way, with warmth and humour and seriousness and compassion and modesty, and all of that.

AG: How long did the editing process for Hard Truths take?

ML: About three to four months. Usual, standard stuff.

AG: Is that how long the editing on your other features has taken?

ML: It depends on the complexity of what we have to do. Obviously, films like Topsy-Turvy (1999) or Peterloo took longer, because there were more technical things to deal with. I meant standard for movies generally. Including mine.

AG: With the world of Hard Truths being more closed-in than some of your other films, what consideration does that bring to the post-production? Do you take a less layered approach?

ML: It’s a red herring, again. I mean, the post-production is the same for every film. My films are very disciplined, because we’re very prepared and the foundations are very solid. What we shoot is very solid and very secure. Therefore, the editing is not about trying to bail out a whole bunch of half-baked, unfinished, inconsequential bits of spaghetti.

We go to the edit with very, very solid material. So, it’s about distilling it in a sophisticated way, and finding the nuances and the best of it all. Basically, that’s the procedure. It’s kind of no different than any other kind of movie. We go through all the various stages, sound recording, music, grading, all those things are all part and parcel.

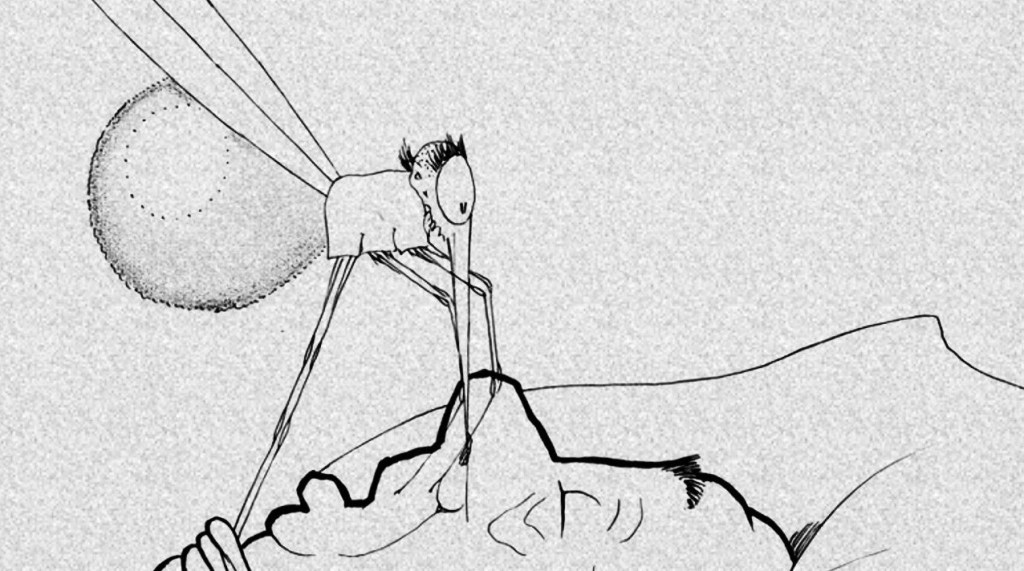

AG: Before our interview I watched Windsor McKay’s animated short How a Mosquito Operates (1912), which you often list as one of your favourite films. What interests you about it?

I wouldn’t say it’s one of my absolute favourite films. But it’s a film I like, it has great character and humour. Really, I say it as a cheeky answer when people ask me for my favourite films.

Hard Truths is now showing in Australian cinemas.

**********

Andréas Giannopoulos is a Melbourne-based filmmaker and co-curator of the Melbourne Cinémathèque.