The Room Next Door, the latest entry in Pedro Almodóvar’s playful and eclectic oeuvre, is a film of conversations. “Am I talking too much?” Tilda Swinton’s Martha self-consciously queries Julianne Moore’s Ingrid, after lamenting her dwindling attention span and capacity for sensuous enjoyment. Martha, a former war correspondent, is dying of cervical cancer after a failed experimental treatment. Listening to music has become too painful, so she now only appreciates birdsong. She thinks about her estranged daughter and the kind of mother she wasn’t. And she talks at length to Ingrid, a successful writer whose newest book is all about learning to “better understand and accept death,” though she hasn’t really.

Martha and Ingrid, old journalism friends, reunite early in the film after years apart. Their friendship is rekindled by Ingrid’s visits to Martha’s hospital room. These early scenes are heavy with reflective monologues and rigid, steady camerawork, as Martha thinks at length, out loud, about her condition and her past. She has spent so much time considering her own death that survival “feels almost disappointing,” and she’s critical of the burdensome hero’s arc of a survivor. Early on, she tells a lengthy, crushing story about the father her daughter never knew. With this latest subject—and periodically over the film’s runtime—The Room Next Door diverges into melodramatic flashback, glimpsing a past that feels caught somewhere between memory and an exaggerated, imagined genre exercise.

After several encounters, Martha reveals to Ingrid that she has obtained a euthanasia pill and wishes to take it within the next month—effectively ‘beating’ her terminal cancer by beating it to the punch. This will take place at a pleasant yet mostly unfamiliar location. But what Martha really needs is for someone to be in the room next door when the deed is done. This duty eventually falls to Ingrid, though she is not Martha’s first or even second choice.

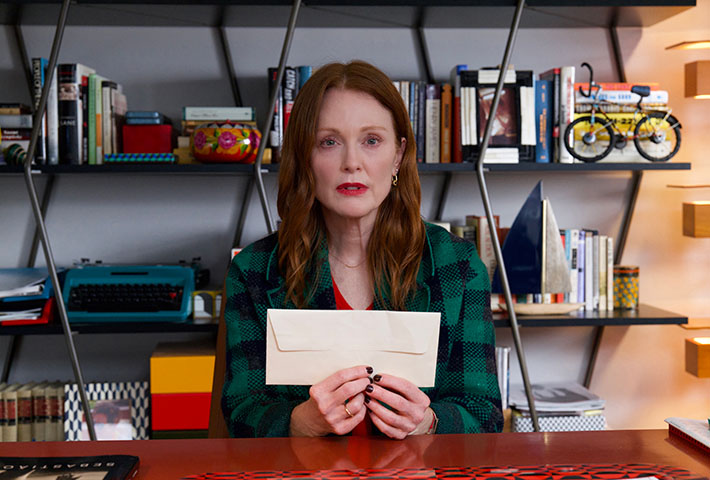

Because of how resolute Martha seems, Ingrid—as her final witness—becomes the far more interesting, quieter character. She is soft and well-meaning, eternally conflicted about their arrangement yet putting much of her life on hold to assist. Still, it is of course Swinton and Moore’s tender and witty dynamic—the sense of a friendship both old and renewed, rich with shared former lovers and continual revelations—that creates more curious ripples in the film’s surface.

The Room Next Door is adapted from the 2020 novel What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez, and Martha and Ingrid’s dialogue signals a certain knowing, ‘literary’ quality. Characters’ pre-digested ideas and musings—some of them cumbersomely expositional, others genuinely fascinating—begin to contradict the inherent instability of Martha and Ingrid’s predicament. This lends everything a slightly off-kilter, though distinctly Almodóvarian, sensibility. Ridiculous lines are played admirably straight. Swinton, inhabiting another of Almodóvar’s complicated mother figures, plays maternal regret with such unvarnished frankness that it begins to feel half-hearted.

Significantly, Almodóvar’s screenplay is interlaced with a great number of references, continually placing the women in relation to other artists’ legacies and reflections. The closing paragraph of James Joyce’s ‘The Dead’ is recited in multiple instances, with Martha seemingly both comforted and distraught by its grand gesture towards the mortality that unites all natural things. There’s a reproduction of a Louise Bourgeois textile work above the couch in Martha’s apartment—I Have Been to Hell and Back. And let me tell you, it was wonderful—beneath which the women discuss another artist, Dora Carrington, around whom Ingrid is focussing her next book. At the house Martha rents to die in, they discuss a reproduction of an Edward Hopper painting, People in the Sun, which depicts a smattering of people on sun lounges. Later, they purposefully recreate the subjects’ same reclined poses. Through this charming tapestry of objects, we begin to see exactly how the women’s cultural lives have been formed, how they relate to each other, and how they wield such worldliness for their own self-assurance.

Almodóvar’s stylistic arsenal is fully utilised here: luxuriously chic costuming and vibrant, detailed set decoration efficiently communicate the material life of the characters, with their good taste and sophistication. Midway through the film, after arriving at the rented house, Martha realises she’s forgotten the very euthanasia pill that lends their trip its purpose. She and Ingrid return to Martha’s apartment and rifle through assemblies of colourful, delicately textured items that, soon, will have no living owner to connect them. The circumstances are ugly and ludicrous—but the objects (lavish fruit bowls and coloured notebooks) are beautiful.

Maybe this is a way of extending grace to the dying, or simply visualising a life’s accumulation. It takes great material privilege to summon any amount of control over one’s own death, and yet it seems no amount of material comfort can shield you from death’s indignities. One begins to feel the women looking for worth in the pain of their circumstances by piecing together meaning from a constellation of texts, artworks, and other peoples’ lives. At times, cinematographer Eduard Grau frames Martha and Ingrid behind or distorted by panes of glass, as if they’re disappearing into and echoing their environments.

Such ideas find their counterpoint in the character of Damian (John Turturro), the women’s shared former lover with whom Ingrid is still in touch. While in town to deliver a lecture on the climate crisis, Damian and Ingrid have lunch. Their conversation drifts toward the question of eventual annihilation. Damian doubts the worth of poetry in an age of mass environmental degradation, while Ingrid insists that “there are many ways to live inside a tragedy.” The sorrow of the film’s characters begins to plainly converse with a much larger grief. Is there any point in rationalising, poeticising, or distracting ourselves from inevitable suffering? Would there be a point to anything if we didn’t?

Though the film experiences frequent tonal swerves—from the plaintive to the melodramatic to the absurd—these ultimately work because, through Swinton’s Martha, The Room Next Door presents a messy, contradictory life glimpsed in retrospect. From warzone assignments to family drama, Martha’s memories suggest a past already incompatible with the present being mourned. The narrative of a dying person’s life appears to come into focus before taking on ever-multiplying distortions and contradictions.

Meanwhile, we watch Ingrid listen to Martha with compassionate interest, helping co-construct her narrative simply by receiving and responding to it. Though Ingrid initially doubts her strength as Martha’s witness, it’s in the final critical weeks that she is made braver by their companionship. It’s difficult in the end not to be moved by the simple, sentimental question underpinning their friendship. Faced with the fractures and nonsense death creates, are you willing to give someone exactly what they need to make it through? Will you find a way, however difficult, to be the kind of person their struggle demands?

The Room Next Door releases in Australian cinemas on December 26.

**********

Tiia Kelly is a film and culture critic, essayist, and the Commissioning Editor for Rough Cut. She is based in Naarm/Melbourne.