When it was announced that Baz Luhrmann would be directing a film about the life of Elvis Presley, it was a match made in maximalist heaven. Of course the director of spectacle, who regularly makes films depicting a hyper-American world, would want to showcase the figure most associated with mid-century Americana. In a Hollywood Reporter profile, Mia Galuppo describes Luhrmann’s obsession with the darkness of Elvis’ story. “[Luhrmann] envisioned leaning more toward Richard II than Bohemian Rhapsody,” she writes, referencing the Freddie Mercury biopic as the genre standard. Throughout this interview, Luhrmann hints at the biopic contradiction: the mythology of Elvis, one that harks back to Greek and Shakespearean tragedies, is what he seeks to capture as a filmmaker. Presley is not the star of the movie; Luhrmann’s interpretation of him is.

Meanwhile, Sam Taylor-Johnson, director of the Amy Winehouse biopic Back to Black (2024), lamented to IndieWire last year that filmmakers have failed to consider Winehouse’s perspective in their retellings. Taylor-Johnson refers to the treatment of Winehouse when she was alive, for example how the press “dissected her life.” By making this biopic, Taylor-Johnson believes she can provide Winehouse (played by Marisa Abela) with some agency. The director accepts and reinforces the terms that biopics are representations of reality rather than interpretations of it. These are terms I struggle to accept.

“There he lay,” says the narrator (Kris Kristofferson) of Todd Haynes’ 2007 Bob Dylan tribute, I’m Not There. “[P]oet, prophet, outlaw, fake, star of electricity, nailed by a Peeping Tom who would soon discover . . . even the ghost was more than one person,” he goes on, immediately blurring the film’s reality with fantasy and illusion. Like Luhrmann’s and Taylor-Johnson’s, Haynes’ ‘biopic’ is concerned with the mythology of a key cultural figure. His film is also interested in alternate perspectives, in a form of storytelling that delves into the cracks of a great idol the world clings onto. The main difference? To quote Haynes in an interview with Cineaste, “You’re in on the joke.”1

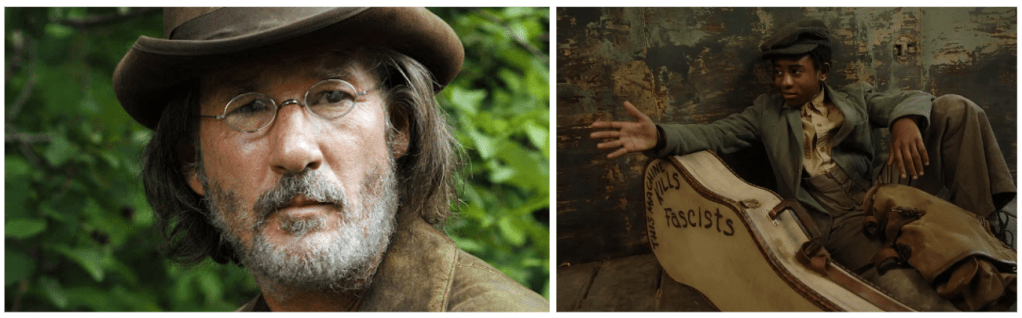

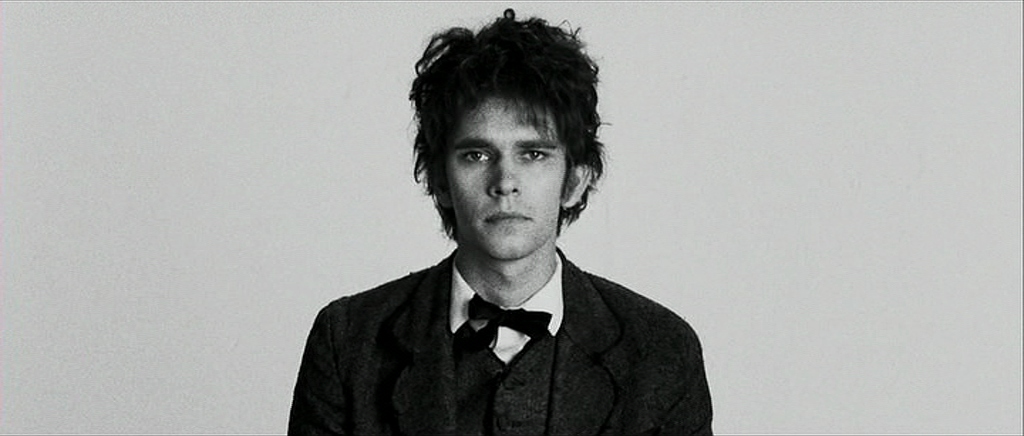

I’m Not There instantly announces its divergence from other biopics by refusing to mention Bob Dylan by name. Instead, it explores the life of Dylan by telling his story through six ‘fictional’ characters. Dylan is: a Black child calling himself Woody Guthrie (Marcus Carl Franklin), the poet Arthur Rimbaud (Ben Whishaw), the documentary subject Jack Rowlins (Christian Bale), the actor Robbie Park (Heath Ledger), the rockstar Jude Quinn (Cate Blanchett), and the Billy the Kid-like runaway (Richard Gere).

In her essay ‘The Pleasures of Verisimilitude in Biographical Fiction Films,’ Anneli Lehtisalo argues that biopics “have defined ‘the degree of truth’” from the film’s beginning.2 Think of the ‘based on a true story’ title cards. This isn’t unique to biopics; other films can do this to deny truth, by claiming that the characters in the film are entirely fictional. I’m Not There does define its truth—insofar as it is marketed and categorised for streaming as a biography—but the opening sequence, accompanied by the text “a film by Todd Haynes” draws a line around how ‘true’ this biography will be.

These characters are not Dylan, they are representations of him, as is Austin Butler’s Elvis and Marisa Abela’s Winehouse. But these multiple representations expose and accentuate Dylan better than a character named ‘Bob’ could. As Haynes continues in the Cineaste interview, “[t]here are moments when the veneer of any famous performer—it doesn’t have to be Dylan—cracks and you see the real pulse or essence of the guy and say, ‘That’s what makes him special.’”3 What is the best way to understand Dylan’s pulse or essence?

* * * *

I’m Not There is not unique in Haynes’ filmography. His first film is the excellent banned biopic of another mid-century musical icon, Karen Carpenter, titled Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1987). Superstar opens with a scene of Carpenter’s mother, Agnes, walking into Karen’s apartment and finding her daughter unconscious. This horror-esque cold open is not what is most intriguing in this film—it is who plays these characters. Carpenter may be mentioned by name, but she is not represented as her ‘real’ self through a human actor. She is instead played by a Barbie doll. This choice captures her perceived ‘essence’ more than a lookalike could. Carpenter is in Superstar who she was reduced to in the culture. What better symbol of American suburbia and its expectations of gender than a Barbie doll?

In Dennis Bingham’s book Whose Lives Are They Anyway? The Biopic as Contemporary Film Genre (2010), he describes Superstar as “Brechtian”4—a word that could be applied to many of Haynes’ works. This is shown, he contends, through the multiple disruptions to the narrative which explain what is happening to Carpenter. This makes the film less about Carpenter and more about the stories that swallowed her. Haynes’ films prevent the viewer from accepting them as reality, encouraging them to question what we are really watching. Instead of using Barbies, in I’m Not There Haynes explores multiple personas to illustrate what Dylan means to the culture that worships him. To quote Roger Ebert, “[b]y creating this kaleidoscope of Dylans, Haynes makes a portrait not of the singer but of our perceptions.”

In her essay, Lehtilaso continues to say that the biopic represents an exaggerated verisimilitude that people seek in all movies. The biopic, however, by defining itself as the truth in its marketing and title cards, plays on a sense of social and cultural realism, which according to Lehtilaso “is connected to public opinion.”5 Biopics are an interpretation of life, but if they are defined as the truth by the filmmaker, then the audience is encouraged to accept their perspective as fact. This is what Taylor-Johnson alludes to in her IndieWire interview; she wanted her filmmaking to reproduce Winehouse’s never-before-seen reality for the audience. It is this manufactured authenticity that Haynes purposefully denies at the start of his ‘biopics.’

I’m Not There starts in black and white with a shot from Blanchett’s ‘Dylan’ perspective as he walks on stage. The unsteadiness of the camera and its positioning teases the voyeuristic impulse of the biopic viewer—will we finally get His story? But as soon as Dylan enters the stage, the film cuts to the title card: a steady long shot of a motorcycle riding across the screen—a reference to Dylan’s infamous motorcycle crash. “There he lies,” the narrator booms, as we see Blanchett’s Dylan in a hospital following the crash. “A devouring public can now share the remains of his sickness.”

“There he lay,” the narrator repeats, before mentioning the poet, prophet, outlaw, fake, and star of electricity. We are told these personas were “nailed by a Peeping Tom” as the film’s visual cues depict Blanchett’s Dylan being dressed for his funeral. With the accusatory phrase “Peeping Tom” playing under what should be a scene of dignity and privacy, the metaphorical death, Haynes points to the audience: the devouring public. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. The diegetic noise after the funeral signals a cut to each Dylan—centre frame, staring directly back at us. It is as if we are shooting the Dylans and replacing one persona with the other.

* * * *

In his book’s conclusion, Bingham writes that biopics “materialise out of a filmmaker’s desire to create drama” from the subject’s life. Biopics are simply a “form of celebrity culture.”6 In his discussion of I’m Not There, Bingham writes, “Haynes understands that in the life of a legendary person fiction might get closer to the truth of the person than do the so-called facts.”7 However, I’m Not There’s wit is not that we get a deeper insight into Dylan’s life, but rather an insight into the culture that creates these personas.

Set to ‘Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again,’ the opening credits do not show clips of Dylan, but rather a grainy black-and-white montage of 60s New York. “Oh, the ragman draws circles up and down the block” is sung over clips of suited commuters beginning their day in the dark. We hear “Can this really be the end?” as the camera tracks across a person in a leather jacket smoking a cigarette. “Well, Shakespeare, [h]e’s in the alley,” soundtracks young people talking in groups on the streets, some waving the camera off. “Can this really be the end?” repeats as miners in an elevator shaft stare down at us with disdain. Each person we see in this montage diffuses the potential of a pleasurable gaze. If we feel so emboldened to look into these people’s lives, then who are we to expect not to be looked back at?

In his 2000 essay on American biopics, academic George F. Custen contends that Hollywood’s obsession with the genre is a natural progression of the fall of the studio system—a way to tell American stories that insists Hollywood executives’ “way of seeing [is] still the right way.”8 As television allowed a closer human connection between viewer and subject, Hollywood cinema had to evolve to encourage insight into different cultural figures’ lives, to “inscribe history from [the viewer’s] point of view.”9 It is the individual who altered the world and not the broader collective. Perhaps this is why Elvis is the ultimate Biopic™: Butler’s Presley is not a complicated historical figure, but rather a palatable man who happened to be on the right side of history—just in private. If this symbol of Americana is still cause for celebration, then so is the culture that chooses to worship him.

I’m Not There asks the audience in the first ten minutes: who made the Bob Dylan we remember? In the credits, we see the ‘America’ Dylan could have been singing about and to. Dylan was not created on his own, and it is not the real Dylan Haynes will be showing us. It is the Dylan the world chose to remember. Haynes himself thinks this way of Dylan; “Yes, and I see [both Godard and Dylan] as interesting and symptomatic examples of the male prerogative of the Sixties,” he tells Cineaste, “as well as typical of the inconsistencies and contradictions of even the progressive… male artists of that era.”10

In his infamous first interview with The Rolling Stone in 1969, Dylan—for lack of a better phrase—gives us nothing. Interviewer Jann Wenner preluded what seemed to be a warning: “Bob was cautious in everything he said.” Dylan answered questions vaguely, from what his new music was going to sound like to when he would tour and how he had some “free-form type thing in mind” for his upcoming television special. The article’s pull quote is “I don’t want anybody to be hung-up… especially over me, or anything I do.” And yet, here we are, awaiting the release of A Complete Unknown starring Timothee Chalamet. We continue to be hung up.

* * * *

I’m Not There rewards the audience, but not an audience who wants to know more about Dylan. It rewards those who accept that they already know all they can. The film’s ending makes this clear. Utilising the song the film is named after, we say a goodbye to three of Dylans’ arcs. Gere’s Billy is a fugitive, leaving via train. Ledger’s actor is taking his kids for the weekend. The lyrics “I was born to love her” soundtrack him driving off and waving goodbye through his rear-view mirror. Blanchett’s Dylan overdoses while his staff circle like vultures.

We see Blanchett’s Dylan again in a repeat of the film’s opening sequence, driving down the road on a motorbike, except this time the crash eventuates—‘Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands’ plays as we see its outcome. The crash is not the ending, though; the music continues as Blanchett’s Dylan is now in the car, talking about ‘his’ music and the nature of the folk genre. “You would think these music people would gather that mystery, you know, is a traditional fact.” This is reminiscent of what Whishaw’s Dylan says at the beginning of the film: “The song is something that walks by itself.”

“Everyone knows I am not a folk singer,” Blanchett’s character says, staring at us through the camera in what plays as a comedic moment. It may be a reference to the criticism directed towards the Dylan Blanchett was based on at the time, but by breaking the fourth wall again, it is also an abrupt awareness that this performance, and therefore this movie, is not real. The film ends as it begins—with diegetic bangs cutting between the six Dylans, followed by a montage. After seeing the ending of Gere’s fugitive, which is similar to how Franklin’s Guthrie character begins, the film cuts to a sepia montage of young people lining up for a Dylan concert. It is only now that we are rewarded with the ‘real’ star playing the harmonica: the traditional folk music Blanchett’s Jude claimed not to play.

This is probably the most obvious of biopic tropes to close out on. An ending clip of the film’s subject blurs truth with fiction to remind the audience that this film has defined itself as real. But as the screen fades, Haynes’ use of this convention reads as subversive—it seems to test the audience about how much, or how little, they have learnt about Dylan. It is another knife in the gut of the genre, a way to say, “If you didn’t get the joke at first, then you should know it by now.” It is this joke that makes I’m Not There one of the more truthful biopics ever made.

I’m Not There can be streamed for free in Australia on SBS On Demand.

**********

Chelsea Daniel is an emerging critic from Mandjoogoordup, WA, currently living in Naarm. Her work has been published in Overland, Antithesis, and Farrago.