In Kelly Reichardt’s Showing Up (2022) Michelle Williams plays Lizzy, a sculptor preparing to open a new show. As she works anxiously at her art, sculpting women caught in various poses and movements, her attention is derailed by a series of impositions and responsibilities: a subtle rivalry with her neglectful landlord and fellow artist Jo (Hong Chau), an injured pigeon suddenly in need of care, an arts administration job, and concern for her brother Sean (John Magaro).

In late October, a screening of Showing Up was hosted by community engagement program Screening Ideas as the opening night for the Symposium ‘A Feminist Ethics of Care.’ In collaboration with the Human Rights and Animal Ethics Research Network, the evening included a post-screening conversation between Anat Pick, Head of the Department of Film at Queen Mary University of London, and Barbara Creed, a Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor at The University of Melbourne.

In collaboration with Screening Ideas, Rough Cut is thrilled to present an excerpt of Creed and Pick’s wide-ranging, insightful discussion.

* * * *

Note: the following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Barbara Creed: I love the film, I’ve seen it a couple of times now, and I can’t believe what a worrier Lizzy is. But I think that’s a lot of her appeal. And maybe we can start off, if I can ask Anat, why she likes the film so much.

Anat Pick: Oh gosh, where do I start? This is definitely my favourite Kelly Reichardt film, which may be a little bit odd because it’s less of a typical Reichardt. I think one of the reasons I was drawn to it initially is because I work obviously in the area of animal cinema, and there’s a lot of trauma and pain and suffering in that field, and so I’m kind of used to watching a lot of very difficult films, and I’m used to speaking about the animal question through that prism of suffering, exploitation. So it was maybe a selfish reason, but it was a relief to watch a film that deals with the animal question in a different way.

The other reason is to do with craft. I think that I would call this a perfect film as an object. It has a particular remit, a particular frame, and then within that, all of the elements seem to work absolutely perfectly. Which I realise may be in contrast with the message of the film, that you have to kind of own imperfections, but I do think that this is really a gem of a piece. It’s a little less loose than Reichardt’s other films and I think it works as a perfect little… almost like one of the figurines that you see in the film.

BC: Before we came to the screening, we had a coffee in Lygon Street at Tiamo and talked about what we might talk about. So, I’ve made some notes on a lot of the things Anat said about the film and some of them I’ll bring up now. One of the things I thought you said, which I found intriguing, was that [Showing Up] aligns Reichardt with a certain kind of feminist filmmaking which has something to do with the difficulty women have in making films today. So maybe you could elaborate on that for us.

AP: I mean, financially, Reichardt always struggles to find funding for her films. She started out by making shorts, which she really didn’t want to do that much. And then there was quite a big gap until she moved to features, and then her sort of breakout film, as it were, was Old Joy in 2006.

And she also has to teach for a living, which I know she loves to do, but nevertheless she has to do that. It’s partly a matter of necessity. So, in these sort of material ways, she is immediately part of a particular kind of practice that many men or male artists are not—not subjected to the same material constraints. I mean, there are other reasons why this film could be considered feminist. We can talk about that if you’d like.

BC: It’s often said her filmmaking belongs also to the movement of slow cinema. That we wait for things to happen and there are long pauses and it’s very reflective of everyday life, which I agree with. But at the same time when I do watch this and some of her other films, I think there’s an intensity, also, about them. Which doesn’t necessarily tie in with my idea of slow cinema, which is more to do with a more meditative kind of filmmaking. And I think, for me, the intensity comes from the fact that her characters—male and female, and in many of her films, the non-human characters, because in fact all of her films have exchanges between the human and the non-human—all seem to be on some kind of inner, intimate journey. And we become sutured into that journey. And it often even creates a strong sense of tension.

So I think that I’m interested in the extent to which that might relate to a similar kind of movement in a lot of feminist filmmaking at the moment. The idea of the main characters in quite a number of feminist films being on their own intimate journey rather than a kind of grand journey. And the films I was thinking of, which we’ve talked about before, and some of you may have seen, The Assistant (2019) directed by Kitty Green, which also has a minimalist style. Even Nomadland (2020), the Chloé Zhao film that starred Frances McDormand. And a lovely film called And Breathe Normally (Ísold Uggadóttir, 2018). It’s an Icelandic film about two lesbian mothers, one of whom is a refugee, an immigrant from Africa who is trying to get into Iceland, but comes into conflict with the authorities. I just wonder whether you felt that Reichardt’s films might share things in common with these other films I’ve mentioned?

AP: First of all, I really like what you said about the sense of intensity. I mean, I guess that’s what I meant earlier when I said that this film is a kind of perfect gem, because there is a kind of intensity to the form itself. And of course, there’s Lizzy, who’s incredibly intense all the time, and I really notice it watching it now. Yeah, I think Reichardt does belong… there are similarities with Chloé Zhao’s films for sure. I also see her very much in the feminist tradition of a film like Wanda (1970), the Barbara Loden film. Films that are about women who undergo something internal and are not so expressive.

There’s a lot of commentary on Reichardt’s films not being rooted in verbal expression. A lot of things go on kind of internally and inside. So that’s one strand of feminist filmmaking, although it’s always tricky to try and label films according to particular formulas. But I think something about a small scale and the kind of inwardness of the film, and the fact that it’s not aligned with a certain showiness that we can think of as associated with the grandeur of male artistry. We see that in the film with Sean. I guess he represents this kind of, the myth of the artist who does grandiose work.

So Reichardt’s characters, and Reichardt herself, make a different kind of film. But of course, more recently, and we talked about that earlier, there’s also this other strand of feminist filmmaking that is much more exuberant. Like The Substance (Coralie Fargeat, 2024) for example, or Love Lies Bleeding (Rose Glass, 2024), that are also feminist films in a very different vein.

BC: Would you think or see any parallels, or just complete differences, between this film and The Substance, which…

AP: They’re so similar! (Laughs)

BC: Both explore the representation of the female body. They have that in common, because by the end of The Substance, that’s kind of what we have, isn’t it, the recreation of the female body? Do you think there’s anything…

AP: Yeah. And actually, The Substance, the word ‘substance’ and thinking about material helps with working out the contrast between these films. [Showing Up] is about clay, about the earth, and The Substance is all about rubber. So that’s how I sort of think of the profound contrast between these two films that offer reflections on embodiment and female embodiment in quite opposing ways.

BC: Yeah, and very original too, I think. There’s been some reference to Reichardt as a kind of queer filmmaker, not necessarily in relation to sexuality, although that may be very relevant in a number of different ways. Because the relationships are so different in her films, but particularly the human and the non-human. There’s a kind of queerness about that. And I thought it was really fantastic the way she becomes so proprietorial in the end about her pigeon, which at the beginning she’s reluctant to bring in. And then the relationship between the two of them, I thought was very sort of intimate and intricate and really believable and credible.

But recently there’s been quite a bit of writing about the way in which narrative films can envelop a sort of queerness. Films like this one and like all of Reichardt’s, which are not caught up with the narrative of the kind of conventional, heterosexual, reproductive couple and the family and the destiny of the couple, which dominates so much of cinema. That in a queer kind of film, there’s a different relationship to time and history.

You can talk really a bit about queer time, which is a time that belongs to the individual, as distinct from the family, and the couple, and the unit. And so many of her characters are sort of lone characters. Committed more, in a way, to their relationships with the non-human than the human. So, I don’t know if you would agree with that.

AP: I, similar to thinking of her as indirectly making feminist films, I think she’s also… there is a queerness about her. You can see it in the kind of unusual pairings of characters. So in Old Joy, for example, there are the two guys heading out into the forest in search of these hot springs, and it’s really about their relationship, which is a friendship, but it also has a kind of homosocial and kind of borderline romantic dimension to it.

But then there’s also the queerness in a more abstract sense of characters straying, characters drifting, characters not fitting into conventions and norms, spaces and times. And that I think can certainly be construed as queer. There’s also, again on the sort of production and milieu side of Reichardt, she has worked with and is very closely associated with someone like Todd Haynes. And as strange as it may sound, Showing Up kind of reminds me of Todd Haynes’ film Safe (1995) even though they’re very, very different. But formally, there is a kind of tightness and clarity to both films that I think connects them.

So I think of her as part of a kind of independent American queer milieu of filmmaking, definitely.

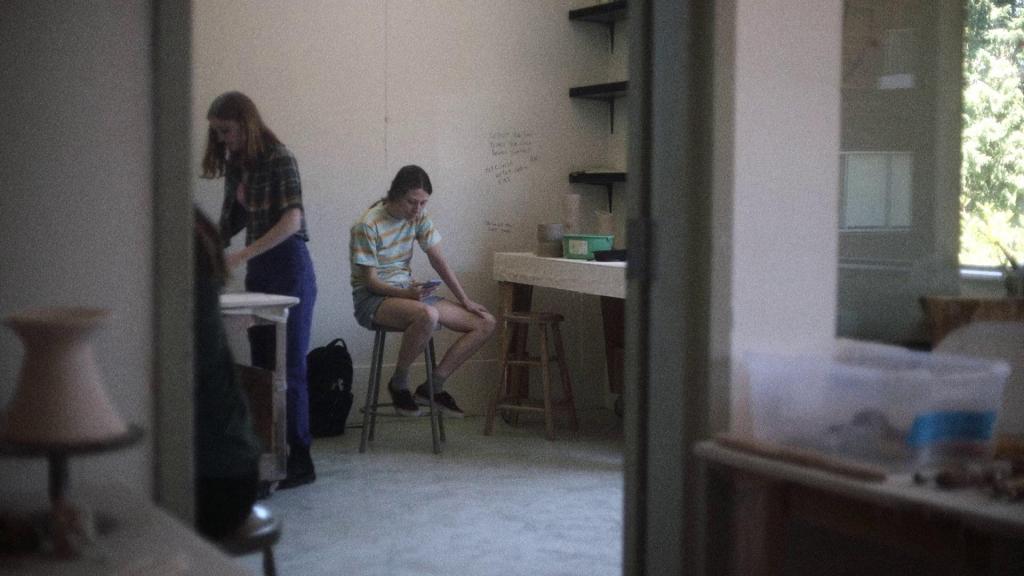

BC: One thing you mentioned which I didn’t realise is that the film is set at the famous Oregon College of Art and Craft. It actually closed down before Reichardt began shooting, [but] was established in 1907. And Reichardt has talked about this and talked a lot about the closure of so many art schools and universities, and sees this as relating to the decline in a lot of universities in the humanities and the arts. And that her film is sort of an elegy to this in a way, a lost time, lost world, that belonged to the universities. So, maybe you could talk a bit more about that. I mean, I think we experience it, all of us.

AP: Yeah, yeah. We experience it also. The UK is undergoing a similar process of the disintegration of the humanities and the marketisation of the university. And that’s definitely the background against which this film was made.

So, I believe that Reichardt had access to the campus of OCAC because it had just recently closed down after more than a hundred years. As you said, it was set up in 1907 to promote arts and crafts in Oregon and it became, I think, one of the centres in the Northwest for pottery and ceramics.

So Reichardt had access to the place and what she did was she actually invited local artists to come and make art while they were shooting the film. So, the people we see in the film making art are actually local artists who came to make use of the space one last time. So, I think it really comes through. I mean, Reichardt’s not a political filmmaker in the same way she’s not an overtly feminist or overtly queer filmmaker, but politics is there. And I think that the location of the film really packs in a lot of that kind of political subtext about the damage of neoliberalism and the destruction of the arts in arts education.

BC: I find it intriguing these days that there’s been definitely a, not so much a renaissance, but there’s been an incredible sort of flourishing of feminist filmmaking and films being made by women in relation to women’s lives, certainly in the last two decades. And I think a lot of these filmmakers have been influenced by the movements happening on the ground, whether it’s #MeToo or Black Lives Matter. Or the whole movement around the environment and global warming and so forth.

Yet almost all of them say, “I’m not a feminist filmmaker. I’m not a political filmmaker. I’m just me and I’m making my creative works.” Yet it seems, to me, quite clear that they are. I mean, they are making films that are speaking about the everyday, the here and now, and the political.

It’s a strange—do you notice that at all?—discrepancy. This sort of disavowed politics, while at the same time a lot of these filmmakers are making very political works.

AP: Yeah, I mean of course there are still filmmakers that make explicitly political and feminist work. I think Reichardt is essentially, in my reading of her, she’s essentially a liberal filmmaker. She comes from a kind of liberal tradition of filmmaking and politics, and so I don’t think of her as radical. As either politically or actually artistically radical, even though there are flourishes of radicalism in this film and in her other films. So, I’m not surprised that she is perhaps reluctant to kind of own the label of feminist. But I mean, do you think it’s a problem or a sign of the times?

BC: I suppose there’s always been a tradition whereby the artist is the artist and doesn’t want to be seen as aligned to political schools or trends or so on and so forth. But I just don’t see how you can divorce the art from the political, myself.

AP: Yeah. I mean, she says she is a political person, but shies away from—or not shies away from, but deliberately avoids—any kind of political messaging in her films. But the politics is definitely there. It’s very much part of this film. I mean, this film is a lot about the material constraints that artists face. So, the whole landlord-tenant relationship is, of course, explicitly a political one.

Showing Up screened on October 21 as part of The University of Melbourne’s ongoing Screening Ideas series. Information on future events can be found here.

This event was supported by The University of Melbourne Faculty of Arts Diversity and Inclusion Small Grants Program.

**********

Anat Pick is Professor of Film and Head of the Department of Film at Queen Mary University of London, UK. She is author of Creaturely Poetics: Animality and Vulnerability in Literature and Film (Columbia University Press, 2011), and co-editor of Screening Nature: Cinema Beyond the Human (Berghahn, 2013) and Religion in Contemporary Thought and Cinema (Edinburgh, 2019). Anat has published widely on animals in film. Her co-edited volume Permacinema: Rootedness, Regeneration, Resistance is forthcoming in 2025, and she is completing a book on the philosopher and mystic Simone Weil and film.

Barbara Creed is Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor Emeritus at the University of Melbourne. She is the author of eight books, including The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis (1993); Darwin’s Screens: Evolutionary Aesthetics, Time and Sexual Display in the Cinema (2009); Stray: Human-Animal Ethics in the Anthropocene, (2017); and Return of the Monstrous-Feminine: Feminist New Wave Cinema (2022). Her recent research is in Feminist New Wave Cinema, ethics in the Anthropocene, and animal/human studies.

**********

With thanks to Screening Ideas programmers Alex Williams and Joel Thompson.