The title Gloria! conjures voices of hallelujah angels pouring out pious song. As if they had been waiting for our company, the film’s opening moments beckon us through Northern Italy’s dappled, cobbled hills to witness a group of young women learn to share a piano.

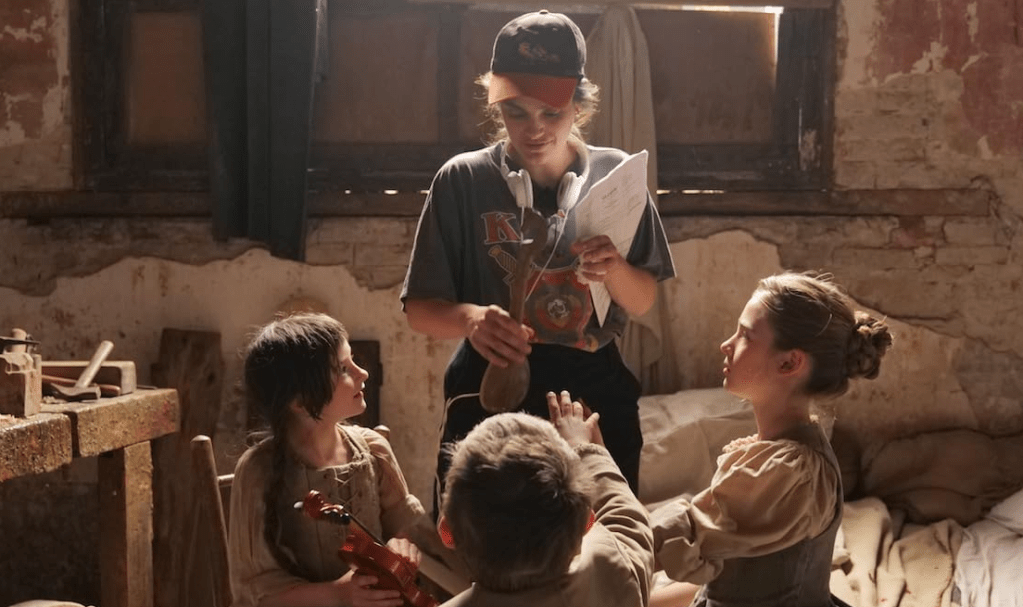

Actor-musician Margherita Vicario’s directorial debut leads with heart and an unapologetic commitment to the young female creatives that history has sought to domesticate. These girls are the orphans of the Sant’Ignazio Institute, a home for displaced young women in the lush north of eighteenth-century Italy. Having been placed into the hands of God—or rather, the Catholic Church—they are members of the institute’s orchestra, classically trained by the church’s patriarch Father Perlina (Paolo Rossi). Sketched in the assured strokes of caricature, Perlina’s conniving instinct for self-preservation is matched only by his lack of musical sensibility. Perlina plays Antonio Salieri to the girls’ burgeoning talents when it becomes known that the town will receive a papal visit in the coming months, and a composition is required for the occasion. It is in anticipation of this divine performance that members of the township turn to music in pursuit of who they wish to become.

We quickly garner the gender inequity present in the small Italian village. Private and prodigious underdog Teresa (Galatéa Bellugi), the mute servant girl who is set apart from the other orphans, discovers a pianoforte hidden in the basement of the monastery. Though manhandled by brow-beating superiors during the day, she teaches herself piano by night with doe-eyed, bucolic aptitude. Musically gifted and befittingly headstrong, Teresa challenges traditional notions of musical merit by bringing a pastoral sincerity to her expression. Though Teresa is forced to share the precious instrument with a group of other classically trained orphans, the sisterhood soon learn to throw off the shroud of stale tradition that pits them against each other, instead using music to channel the undeniable richness of being a young woman.

Gloria!’s refrain is one of joyful resistance. This is captured in Christian Marsiglia’s rhythmic editing, which echoes the sentiment of the girls’ music—as well as the tempo of their lives—through a heavy use of montage. The musicality of the editing lends itself to a sensuous viewing experience that calls forward a certain legato in the storytelling. The leaping cuts allow us to not only understand but to feel the tension in the tug of war that is tradition versus unorthodoxy. Whether it be composing for the upcoming papal visit or confronting the men pulling the strings in the women’s lives, the music they create together through feeling and improvisation heralds a rebellion that dispels the pomp and expectation that surrounds them in a classical context. When we watch Teresa compose night after night, we are watching a representation of history that remembers art made for different reasons—for an expression that is arguably less refined, but also less stunted.

Gloria! rides the lip of genre, spiting the traditions that hold down dissenting voices. Using a feminised lens that damns the stuffy notions of the early eighteenth-century Italian baroque composers (equated with a traditionally masculine approach to music), Vicario upholds the liberation that iterative creativity is laced with. The film’s subversion of genre is the subversion of a patriarchal ideal, an ideal which aligns itself with a classical way of playing and composing music. Vicario calls on the tropes of musical theatre without parroting the canon of musicals that have come before. Despite the opening scene’s use of dance and song, the film doesn’t return to this cinematic convention until its final moments.

Vicario utilises opening and closing musical numbers for their impact within the world of the story, not because genre calls her to use song regularly or arbitrarily, and in doing so she cultivates an elasticity between diegetic and non-diegetic sonic worlds. The characters engage with the music we hear within the world of the story—not just to satisfy the requirements of the musical genre, but to satiate their own creative urges. The young women are always driving the use of music in the film; we even watch as Teresa composes the film’s central refrain. Through this process, we bear witness to a film that writes its own rules about how to use music to tell the story of history’s unsung composers.

Throughout, the film demonstrates the power of music through a feminine sensibility that rejects classical, patriarchal convention. This contest between traditional musical prowess and a more progressive, relaxed musicality is illustrated in the relationship between Teresa and highly strung first string Lucia (Carlotta Gamba). At first—nose slightly scrunched and flooded with memories of the clunky early ‘jamming’ I used to indulge in when I played piano myself as a child—I braced against the kitschy style that Teresa hones through her more sentimental way of knowing music. Compared to the music Lucia champions (the straight-backed adagios and minutes of the time), Teresa’s instinctive, almost jazzy time signatures and melodies produce an unrefined (yet often spirited) comparison.

This dissonance brings a conflict into focus: the earnestness of the exploratory music Teresa plays tenses against the casual authority of Lucia’s excellence. But Gloria! doesn’t ask us to pick a fighter. Although Lucia and Teresa are at odds in their expressive styles and technical skill, these young women aren’t pitted against each other in the dominant language of modern cinematic patriarchy. As their animosity morphs into a friendship of mutual respect, Vicario uses this relationship to illustrate the way that dominant ideologies can pit differences against one another. In the end, the friendship Teresa and Lucia find releases them from competitive enmity, and they are both richer for it.

I became aware I’d been conflating a feminine perspective with qualities of ‘the amateur.’ What I really walked away from Gloria! with was an appreciation of the gentleness and bizarreness of beginnings—of learning something new. Of how not to know how, and to attempt. Learning is not an inherently feminine task, but there is a playful grace inherent in the experimentation and improvisation of branching out from ourselves. Early renditions will rarely possess the refined sounds of dominant practices, but this newness sparkles with something more valuable: authenticity.

Being musically authentic can hold great power, but it can also take great courage. When young cellist Bettina (Veronica Lucchesi) writes and performs a song for her comrades one midnight around the piano, it is apparent she has taken a risk to express her story to her peers. The musical conventions she usually hides behind have been stripped away, and her voice quivers with genuine intent.

Gloria! knows of its own earnestness; this is the point. Its anthems are dripping with sentiment, sometimes to the point of saccharine theatre. If the film had abstained from leaving us with the images of free young women running over the Napoleonic Northern borders that Maria von Trapp would come to gratefully traipse some century and a half later, it might have left a more sophisticated impression. That said, this retrospective activation of period drama girl world champions a prevailing peasant with ecstatic joy. The mood of the film inherits its message: those who have been silenced can change the world, and sharing the piano is the best place to start.

Gloria! screens across Australia as part of this year’s St. Ali Italian Film Festival.

**********

Ruby O’Sullivan-Belfrage gleans creative energy from the synergy produced at the intersection of disciplines, particularly that of film, sound design, and writing. She is the founding editor of Deco Radio, an audio journal that places sonic and literary artworks in conversation. Ruby has a background in film production and cinema studies. She works and plays on unceded Wurundjeri land.