There are three moments in Luca Guadagnino’s I Am Love (2009) that I believe capture the essence of what love means to the Italian director: a whorish prawn dish, a fuck in tall grass, and two lovers holding each other in the dark. Together, these moments represent the triptych that divides so many of his films: being in love, lovers, and having loved.

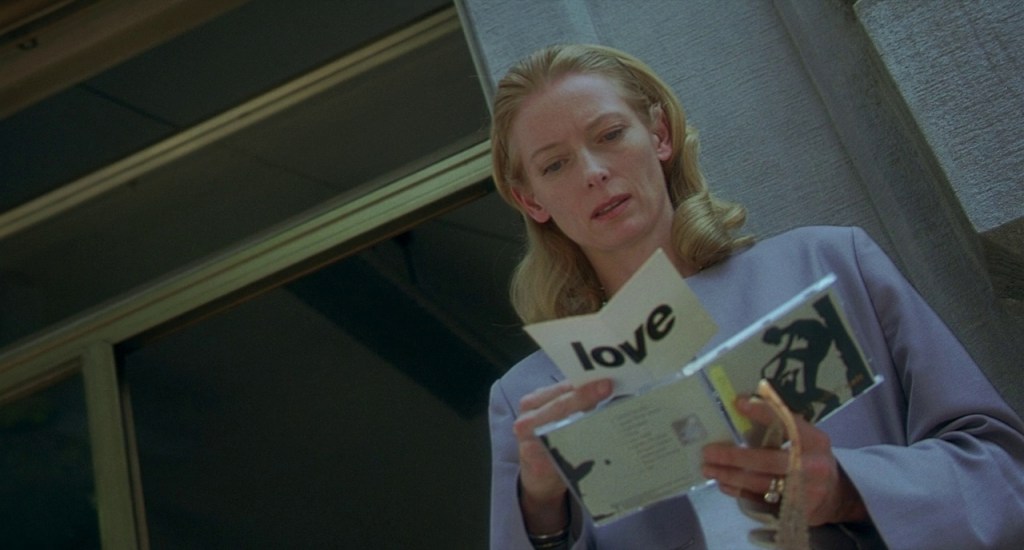

Guadagnino’s first film, The Protagonists (1999), follows two Oxford teenagers who murder a man just because they want to. But it begins with Tilda Swinton telling us about love. “And so here we are,” her voiceover croons as two people make out in slow motion. “Friends and lovers, beating hearts; caught in this joyful moment. ‘Cause all the world loves lovers, all the world loves people in love. Isn’t it true?” It’s true for Guadagnino of course, who in twenty years has amassed a reputation as one of our most accomplished filmmakers when it comes to capturing romance and desire.

But in a Guadagnino film, love is never as simple as you might want it to be. Swinton’s treatise introduces us to a meta-documentary about a very real murder. Any romance in the image of those “beating hearts” feels undercut by the anticipation of the gory death that will soon stop them. For this reason, it’s as good an example as you’re likely to find of how love appears in Guadagnino’s work—haunted by the question of its limits.

It takes someone with a romantic’s faith to test these limits. Guadagnino might have shed the explicit postmodern sensibility that defined The Protagonists, but it’s still there in the way he turns love in on itself; always questioning how it informs the way we watch and feel our way through his films. There’s an aesthetic self-reflexivity that stops us from ever truly escaping into the love we’re watching play out. It’s not impersonal, more an affective ‘edging’; an air of detachment that shadows his melodrama, as if he never wants us to lose sight of the fact that we are only watching a simulacrum of love. It’s rich and sumptuous, but not completely filling.

Many have critiqued this aspect of Guadagnino’s filmmaking, declaring that his often meta understanding of love is coldly removed from its emotional reality. Richard Brody’s accusation that Call Me By Your Name represents a “clinical” and “empty” version of first love seems to be an attempt to name this distance. It makes sense that we’d be sensitive to the limits of Guadagnino’s evocation of love’s intimacy, or his tendency to cut away during sex scenes. ‘How Does Challengers Make a Love Triangle Feel So Empty?’ Brody asks in his review of the 2024 threesome-centred box-office hit. He’s meant to be a director of excess, after all. Everything—whether luscious design or sensual camera work—is dripping in romanticism and sentiment that betrays, or so we think, his desire to make us feel romantic and sentimental. But it’s more important to Guadagnino that we go into his films like bricked up teens walking into a strip club expecting to see or feel desire. From there he can truly fuck with us.

This is why Guadagnino so often throws love into the lion’s den of genres hostile to it: cannibalistic body horror, crime thriller, mockumentary. In form as much as in content he pokes and prods at the love he so joyously recreates, asking: when will you no longer be able to recognise it? When two cannibals strip a man of his flesh down to the bone together? When Armie Hammer (almost) eats a cum peach or a son dies after finding out about his mother’s love affair? When will you question the love I’m showing you enough not to feel it, not to yearn for something like it?

The answer offered by I Am Love, with horror as much as hope, is an orgiastic never.

In Love:

In Guadagnino’s films, love is a thing that makes the world edible. I think of Dakota Johnson tearing a bloodied yonic opening in her skin just above her sternum at the end of 2018’s Suspiria. It’s next to her heart, but it’s closer still to her oesophagus: a new way to consume as much as to consummate. Being in love with someone and ingesting them are the same thing for Guadagnino. His lovers seek out their desires like insatiable cravings, love’s anticipation akin to the pangs of hunger, its absence like starvation. On Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread (2017), Guadagnino said: “It is a film about the essence of love. She poisons him, and he lets her poison him!”

I think of Swinton basking in the glow of a delicious prawn in I Am Love as our lead, Emma. This moment—“prawnography,” Swinton has called it—is the exemplar for Guadagnino’s career-long obsession with connecting love and food. The meal has been prepared by her soon-to-be lover, Antonio (Edoardo Gabbriellini), and it’s the horniest thing you’ve ever seen: red prawn flesh glossy with sauce, plated up like a Kandinsky—a mix of bold lines and colourful splotches. Emma’s mouth—her lips just as glossy as the prawn—is open. The world around her is almost completely silent but for the hard metal ting of her knife hitting the plate and cutting through John Adams’ rich score—the emotional spine of the entire film—as it repeats a sumptuous, string-heavy riff.

But the theatrical spectacle of this dish is just a decadent means of emphasising how subjective the experience of eating it really is. We might gawk at the prawn—its beauty so immense it lights up Emma’s face—but it’s gone as soon as she begins to eat it, lost behind Swinton’s closed eyes and pursed lips. We know it must taste fucking delicious; there’s the warm yellow illumination, Adams’ strings swelling ever louder; Yorick Le Saux’s camera is tight on Swinton’s gaze, savouring the micro expressions behind every indulgent chew. Guadagnino wants us to see others feel pleasure without truly knowing that pleasure. This is the air of yearning that always dogs at the heels of his love on-screen. How does the prawn actually taste? That’s none of our business. We are being edged with the fulfilment of a pleasurable experience we see enough of to want. The prawn’s significance as a symbol for the budding love between Emma and this cook only adds fuel to the fire—another reason to crave its taste, another felt experience withheld behind a tantalising aesthetic.

The final moment of ecstasy is Emma’s alone to experience, and ours to envy. It would be easier to bear if Guadagnino could just let us be voyeurs, but we’re brought too close to the experience for that. He might not be able to escape cinema’s formal limits, but he can use his stylish theatricality to suspend our disbelief a little bit. Watching Swinton is like eating with a cold, frustrated that you can’t taste the food as much as you want to.

Lovers:

The screen goes black after the opening narration of Guadagnino’s The Protagonist. In the dark we’re left alone with nothing but the sound of moaning—five seconds with those “beating hearts” evoked with just one breath. These are Guadagnino’s lovers. They don’t kiss; they breathe as one. They don’t fuck; they congeal. William S. Burroughs (whose 1985 novel Queer Guadagnino has just adapted) has a word for this, ‘schlup’[1]: the complete fusion of lovers. “To enter the other’s body, to breathe with his lungs, see with his eyes, learn the feel of his viscera and genitals.”[2]

Our two beating hearts in I Am Love belong to Emma and Antonio: a Russian émigré unhappily married to Milan’s richest textile mogul and a budding-chef-cum-hunky-introvert. They meet on the threshold of the Recchi family mansion with Antonio holding a cake, lightly dusted in snow, and Emma wearing the tight-lipped poise of the Milanese aristocracy. It’s not until an hour into the film that the pair actually get together, and it’s in classic Guadagnino fashion—the blurry outline of a two-second kiss coated in the rich colours of an Italian summer.

They fuck, at last, ten minutes later. Antonio takes off Emma’s clothes with a ritualistic detachment. The sex is off-screen, but we get a collage of its artefacts: lingerie and jewellery dangling off a grey couch, an open window, crumpled jeans. Underscoring every shot is the sound of Emma and Antonio moaning: one breath. They don’t speak much—though Emma monologues about a soup recipe before they fuck again—but live these days as if they’re also one body.

Each sex scene between the pair places us in the thick of it, among the downy fluff above Antonio’s ass, the goosebumps encircling Emma’s nipple, the sweat pooling in the dip of a collarbone that might belong to either one of them. As with all of Guadagnino’s lovers, Emma and Antonio become one, a ‘schlup,’ rolling in the grass under a scorching sun in the hills just outside of Milan. It’s horny, but there’s an oddly aloof undercurrent to it, as if the pair are ignoring us. Our view is often obstructed by grass or crickets, the camera giving the pair privacy to have the complete experience to themselves. Their relationship feels idealistic in its insularity, even utopian. Their love is a thing of the countryside, separated from the world and the city. Deep beneath the surface are the noir-esque stakes of adultery, a splash of the Hitchcockian crime thriller Guadagnino leans into throughout the film, as Emma darts through cobblestone streets searching for Antonio or sneaks down into the kitchen to steal a panicked kiss.

But these coiling, sweat-covered limbs also have an air of body horror about them. On-screen, ‘schlup’ feels quietly threatening. Losing track of your own body during the throes of passion can be horrifying. Moments when you start seeing yourself less as one complete body and more as parts of you giving pleasure to parts of him are as threatening in their vulnerability as they are liberating.

This is the essential, defining trait of the aesthetic language Guadagnino constructs around his lovers: a formal interest in the way love atomises the body. To be a lover is to see yourself split apart under the other’s eye; a vivisection at once horrifying and generative, which Le Saux’s camera replicates in rapturous close-ups of hands, veins, napes, and moles. The sensation of love here is an impossibly small amalgam of the tiniest sensations that we’re unable to bring together into one complete picture or summative phrase; you feel it in parts and struggle to assemble it into a whole with words like ‘love.’ It’s no wonder ecstasy is so often expressed wordlessly. It’s no wonder Emma and Antonio are so often silent, watching each other with their mouths open, as if waiting to eat each other up. Guadagnino is not being withholding; he is making his point loudly—their love is theirs, and we can only see and hear enough to crave it, enough to want to try and name it.

Having Loved:

In I Am Love, the first spark between Emma and Antonio begins as light as snowfall. Antonio stands on the threshold of the Recchi’s Milanese mansion, covered in snowflakes. We watch them melt into his coat as he shows Emma his cake, their transience the perfect representation of a meet cute. The metaphor, like all of Guadagnino’s metaphors, is simple and anchored by something essential to love’s feeling. Each snowflake is an entirely unique, fragile, and momentary pleasure, landing and melting quickly.

Snow never returns in I Am Love. The rest of the film is sun-dappled and scorching. Emma seeks out Antonio through sunburnt, cobblestone streets as if dehydrated, and they drink each other up. They’re dripping in sweat while they fuck. Or they’re shrouded in steam as they lean over a soup they’ve made together. It’s another Guadagnino trope: love held captive by summer and water. The point, once again, is to tease us with a limit. What will happen to Emma and Antonio when winter returns, and the snowflake of a meet cute thickens and sticks? After all, snow is the backdrop for heartbreak in 2017’s Call Me By Your Name, the last of Guadagnino’s ‘Desire Trilogy’ and another film about a summer love haunted by the inevitability of its end. There, Oliver’s (Armie Hammer) absence is the damp aftertaste in Elio’s (Timothée Chalamet) mouth and the cold reminder of having loved him (cue Sufjan Stevens).

The first time I watched I Am Love, on a dirty laptop during an unseasonably hot summer, I was in love. The second time I saw it, last month on its fifteenth anniversary, I wasn’t. Part of what makes Guadagnino’s representation of love so affecting is its ability to hold and evoke both experiences at once: loving and having loved; in love and out of love; a lover and not.

In a mid-credits scene at the end of I Am Love, Emma and Antonio are in a cave together, fully clothed in a silent embrace. Beside them, a light on the cave wall shimmers like the bottom of the ocean. Adams’ score echoes as if arriving from a great distance. It’s not romantic, at least not wholly; it’s two people in the dirt and the dark, rolling about, utterly separate from the world. If this is utopia, it’s muddy and solipsistic. Guadagnino seems to be referencing Plato’s famous allegory—a favourite among film theorists—of the cave here. A group of people spend their lives chained in a cave watching shadows projected on a wall. Eventually, they see these shadows as their reality. Are Emma and Antonio living in delusion? Is that all love is in the end, a projection that reveals how easily we can be trapped into thinking we recognise something that, in reality, still escapes us? For Guadagnino, it’s clear: it doesn’t matter. Emma and Antonio are together all the same.

In the end, Guadagnino offers them his greatest gift, one none of his other on-screen couples have been afforded: a loving honeymoon period allowed to play out after the film ends, without us watching on. There, in that fictional future, we can believe that they are still somehow intertwined in that cave, with their eyes and lips barely discernible against its pitch black, and their legs moving together as one. For two hours, we’ve watched this couple be both love’s shadow on the cave wall and its reality at once. But this is just semantics; either way they’ll be holding each other long after we’ve stopped watching them.

This is the tragedy and joy of love in Guadagnino’s work—not that it is unreal or ultimately doomed, but that it will inevitably change our realities either way. Love, whether seen in a projection on a cave wall or in an ex you notice in the lobby after a retrospective screening of I Am Love, does not know time or distance, and it doesn’t care about pain or truth or the distortions of memory. Its feeling becomes our reality all the same, even if only for a moment.

In the dark, a couple kiss before the credits roll.

I Am Love is currently available to stream on MUBI Australia.

**********

Guy Webster is a theatre critic, dramaturg, and moonlighting academic living on unceded Wurundjeri land.

[1] The term appears throughout Burroughs’ 1959 novel Naked Lunch.

[2] Excerpted from Burroughs’ Queer.