For the third instalment of our ‘Beyond the Frame’ column, Rough Cut speaks to two thirds of the team behind moviejuice, a film collective out of Adelaide. Since their inaugural 2023 backyard screening, Shea Gallagher, Daniel Tune, and Louis Campbell have been showing under-seen Australian gems and experimental works from across the world, often collaborating on events with local musicians. In this conversation, Shea and Daniel discuss their origins as a group, the ethos behind their eclectic programming, the importance of fostering a welcoming community, the vibrant “cross-contamination” of music and cinema, and much more.

Rough Cut: Can you tell us about the origins of moviejuice? What inspired you to start up a film collective—and how has the moviejuice community grown since?

Shea Gallagher: Moviejuice sprouted from the experiences the three of us had at the 2022 Adelaide Film Festival (AFF). Daniel and I had met at the Adelaide Cinémathèque a few years prior, and Louis [Campbell] and I were doing a uni class on film curation. The three of us linked up while doing some work for AFF in various capacities. We had all seen John Hughes and Tom Zubrycki’s documentary Senses of Cinema (2022), about the Australian film co-ops of the 60s and 70s, which spoke to us as cinephiles who’d bemoaned the lack of an alternative screen culture in Adelaide. Catching Tim Carlier’s inspiring microbudget comedy Paco (2023) at the end of the festival made us realise that not only was there exciting experimental work being made locally, but there was huge untapped potential for passionate, community-minded cinema to thrive here.

The indie music scene in Adelaide is famously robust and supportive, and given that we were already sort of enmeshed in that community, we were able to organise our first screening event in a backyard with some local bands, which became the program model we wanted to continue going forward: films and music in the one event. We’ve found there to be plenty of overlap between the music and film communities so it makes sense to facilitate both, but we are also trying to erode barriers between these various niches that might be considered otherwise separate. Cinema and music are such multi-faceted art forms already that there’s plenty of opportunity for cross-contamination, especially on an underground level.

Since our first screening, the moviejuice community has blossomed into something that feels a little beyond us, yet is still finding its feet. We have met so many incredible people locally through our events, but also connected with similar-minded people and groups interstate. While we are a fully independent organisation, the nature of moviejuice is inherently collaborative and we have been lucky to work with other groups like Static Vision and Underexposed to put on some really exciting events. Every one of our screenings has been a hugely collaborative effort, whether that’s with venues willing to facilitate us or simply the many people who are always happy to help us set up and pack up. For us, we want the community to feel as involved in these events as possible because that’s the only way these things can continue.

RC: You mention that music and film really come together in your screening events, whether through pre-film performances or improvised live scores. Can you speak to the relationship between music and cinema? What is so special about live scores, and how have your audiences responded to them?

SG: On an audience level, the relationship between music and cinema has been so important to us, as it’s the intersection of these two things that have been at the crux of our events from day one. We want our audience to interact with the films we show similarly to how one engages with live music—we want it to be an open and intimate experience, where the sharing of the art becomes as important as the art itself. Having live music at our screenings helps people feel that connectedness to each other and to the work.

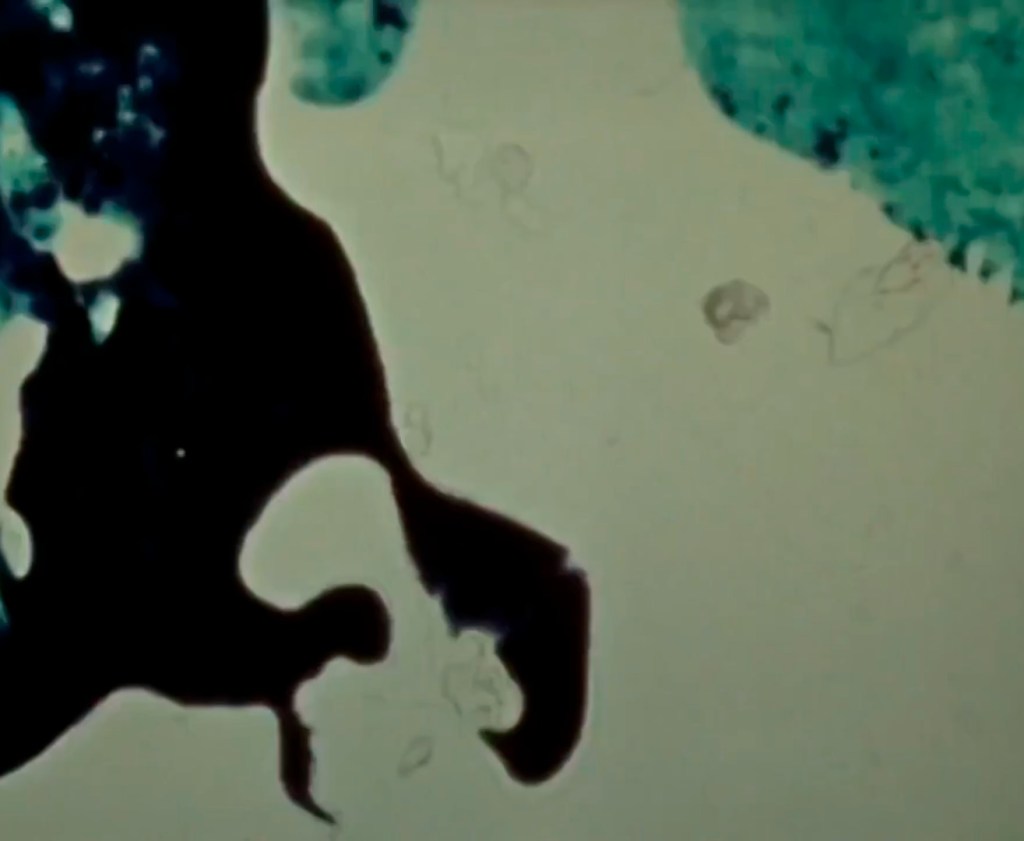

Normally this takes the form of local bands playing post-screening in a kind of afterparty atmosphere, but we’ve had artists play before the film to set the mood too. We had wanted to try a live score screening for a long time, because they are kind of the ultimate example of putting a work into a new context and bringing the spontaneous, DIY ethos of our screenings right to the fore. We’re not the first people to present [Stan Brakhage’s] Dog Star Man (1961-64) with a live score, but we tried to put our own spin on it: screening a faded 16mm print in a bar basement with live musical accompaniment that was totally improvised. Thea Martin and Luka Kilgariff-Johnson are much-loved in the live music scene here so it was thrilling to have them be open to trying something so out there, and the result was very special.

Of course Dog Star Man is intended to be watched silently, but I think the screening stayed completely true to Brakhage’s intention to have the audience experience an “adventure of perception” with the film. Rather than inform the audience’s viewing, the score almost seemed to act like a bridge between the audience and the images, allowing people to tap into the immediate, stream-of-consciousness quality of the film. There was such an interesting mix of feedback afterwards—people who’d never had any exposure to experimental cinema coming away with completely new ideas (or being bored out of their minds).

Live scores are definitely something we’d love to try again, as it’s a really under-utilised form of viewing and there is so much potential to create something new and reach an audience in a different way.

RC: There’s a real diversity in your programming, in terms of style, genre, and origin. You’ve screened a lot of locally made films, as well as works of cult and avant-garde international cinema, like Dog Star Man or Toshio Matsumoto’s Funeral Parade of Roses (1969). Can you speak to some of the considerations that go into your choices?

Daniel Tune: I think the major consideration of our programming is a political one. The hope is that every film we show has some potential to radicalise people, even if it’s just radicalising them to the possibility of seeing something in cinema and the world that they hadn’t before.

Our programming was initially purely Australian, and that’s still the emphasis. So much of the best cinema this country produces is completely marginal, unheralded by most cultural institutions and largely unseen by the public as a result. So it feels like there’s an imperative to get those films in front of people. There’s something really empowering about seeing something cool being done cheaply and independently in the place you live—it’s the feeling that got us to start moviejuice in the first place. Ideally we are just paying that feeling forward.

But as we have gone on and (hopefully) built up some goodwill with our audience, we’ve tried to expand our programming to have space for anything that offers an alternative kind of cinema to that presented in commercial venues. It’s a very broad criteria, and there’s definitely a patchwork quality to our events. But I’d like to think there is a unifying ethos in them, even if it’s just that they all present people with images and ideas that they’re not seeing in commercial screening spaces.

RC: Do you have any advice for readers who might want to start their own DIY film collectives—particularly for young film lovers living outside of cosmopolitan centres?

DT: The thing that has been kind of shocking about getting moviejuice going is how easy it has been. Not necessarily on an organisational level—every event is kind of a headache, though never so much that it isn’t worth the buzz that we all get from doing it. But it’s surprising how easy it has been to get people interested, in a way that I find very hopeful.

If you’re living in a place like Adelaide, where alternative film culture is close to dead and you’re frustrated that the kind of thing groups like us offer doesn’t exist, the chances are there are enough other equally frustrated people around to form a decent core audience for whatever it is you’re doing. I think it’s generally true that people like to see cool shit happen and they want to be a part of it, despite what certain sinister parties might be telling you. It’s just a matter of finding those people, which mostly comes down to telling enough people that the word starts to spread.

I guess the other practical advice I’d give is you don’t need to go through any kind of commercial or cultural institution, especially not to start with. Moviejuice’s first screening was in a backyard. At the time we thought it was kind of ridiculous that we couldn’t get any cinema to host us at a price that was affordable for a bunch of uni students (which it was and still is), and the backyard screening was a bit of a fuck you. In retrospect I think it was the best possible venue. It very much set the terms for what we want to do—a community-first model of cinema, based on DIY principles. You lose out on some technical quality or standard comforts, but you gain a feeling and an energy that you’re never going to get in a traditional cinema. You realise in your bones that you really don’t need anyone but your own community to make something interesting happen, which to us has been a very powerful piece of knowledge.

RC: At the end of this month, on September 28th, you’re screening the ‘unclassifiable’ Australian indie Paris Funeral, 1972 (2021), which will include an introduction and Q&A with director Adam C. Briggs. Can you tell readers a bit about the film and how the event came about?

SG: We were introduced to Adam C. Briggs through a mutual friend, filmmaker Allison Chhorn, and were completely taken by Paris Funeral, 1972. It’s the exact kind of unique object we love to champion. It’s unclassifiable in the sense that it’s exploring the docufiction mode in such a strange new way—it’s a warm, intimate film but also intensely alienating at times, and the conflict between those feelings is something that we thought would be interesting for an audience to experience at a moviejuice screening. We always like to include the filmmakers in the screenings as strongly as possible—whether it be an intro or a Q&A, having the artist there makes the work more accessible and more alive, so we’re so excited to have Adam make the trek from Meanjin to present his film, along with his short My Home Is a Dog That Lives Inside Me (2017). Briggs also has his terrific new short Write a Letter (2024) playing at Adelaide Film Festival this year, and we would strongly encourage people to keep their eyes out for it there and beyond!

**********

Moviejuice’s next screening, Paris Funeral, 1972, takes place on September 28 at Windsor Theatres, featuring a Q&A with director Adam C. Briggs. You can find tickets and more information here.

Follow moviejuice on Instagram and Facebook to stay updated about future events.