In 1991, the then-aspiring artist Matthew Barney video-taped himself climbing the walls of the Gladstone Gallery fully nude. Equipped only with a climbing harness, Barney installed ice screws along the walls and ceiling, making his way through the gallery space, down a flight of stairs, and into a large walk-in refrigerator. Titled Blind Perineum in reference to the tissue between the anus and the genitals, Barney’s work is but one example of how performance art showcases the willingness of the artist to endure feats of strength, durability, and most importantly—pain.

In 2023, I was bouldering in St Peters at a climbing gym, just a few weeks before my birthday. I was midway through a slab climb—one in which the top of the climb is perpendicular to the floor, so that it requires enormous amounts of cool-headedness, patience, precision, and balance. My body was splayed out against the wall, my right hand gripping a small crimp in-between my middle and ring fingers, my feet standing precariously on two separate, dual-textured holds, and my face drenched in sweat. Reaching perilously out towards the next hold with my left hand, the smooth footing betrayed me and I was lurched downwards, the entire weight of my body bearing on my two fingers gripped at an awkward angle. What followed was the sound of what I can only describe as hard plastic snapping, and I was sent careening down by gravity, landing on the mats below.

My girlfriend drove us to Canterbury Hospital that evening, where I received minor treatment and advice to go to Concord Medical Hospital in the next few days. The news was dire: the bones in my hand had split, and I needed to have screws installed. What transpired was surgery, followed by two months of hand therapy, in which every hour, on the hour, I had to perform a repetitive series of movements (opening and closing fist, lifting fingers up off a table one by one, opening and closing palm, etcetera). These movements started simply and then became more complex, involving differently strengthened rubber bands.

When my bandages first came off in the days after surgery, I was unphased by the sight of my wound and stitches, but what shook me was my sheer inability to move any part of my body from the wrist up. I almost cried when the act of wiggling a finger was too much to bear. These exercises helped bring back this mobility, but at first it was torturous, as I was only able to do a few at a time before giving up out of pain.

I have always had a low pain tolerance, which made my admiration for performance artists and stunts in movies all the stronger. I envied these people’s abilities to shrug off jumping through windows, getting beaten up, or climbing down ladders made of knives. One of my favourite film series, Mission: Impossible, features a stunt gone wrong in its sixth instalment, Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018), in which Tom Cruise mistimes a jump and his shin hits the edge of a building. For a franchise that now advertises itself as Cruise’s own personal death wish, as he elects to perform all the stunts himself in-camera, it’s daring that the filmmakers chose to include one of the few times he didn’t make it. Even so, Cruise, the ever-cool performer, merely limps away from an injury that would have had me clutching my leg and crying on the ground.

For many non-climbers, there are very few cultural touchstones they can point to for examples of what bouldering looks like. Funnily enough, Mission: Impossible 2 (2000) is bookended by two sequences of Cruise’s Ethan Hunt bouldering, first in the deserts of Utah, then on a seaside cliff face near the climax. Besides this, the main point of reference is 2018’s Free Solo, the documentary detailing Alex Honnold’s arduous journey up the side of El Capitan. A sweat-inducing, nerve-racking watch, this serves as a better representation of the sport than Cruise’s highly edited leaps between ledges and his tendency to catch himself via his fingertips. What both films leave out, however, is the aftermath: the recovery period that follows such an endurance-reliant sport.

As I began my recovery, I kept the hand therapy as a very private act: I would seclude myself in my room or go out the back at work. For some reason, the act of moving my hand in these repetitive motions (up, down, back, right, clench, unclench) was embarrassing, largely due to my inability to get it right straight away. It was as if I was a failure for being unable to simply limp away like Tom Cruise, like it should be easy. I wished I could strap some magic device to my hand to make it all better, like Bruce Wayne in The Dark Knight Rises (2012), whose eight years of dealing with a broken leg is instantly cast aside through some unnamed piece of science-fiction novum that attaches to his leg and clenches his bones together, so that he is now able to walk as freely as he ever had before.

This process of healing became my own little performance for an audience of one. I was watching myself endure this pain, and I soon began to feel some sense of catharsis as that wiggle of the finger became easier day by day.

* * * *

Performance art is often about physical pain and the artist’s ability to endure it. But these performances do not usually address the practice of healing, of recovering and treating wounds, of having to live with it. Blind Perineum is a work loaded with symbolism, with Barney’s career-long preoccupations with masculinity on full display—his climber character embodying a strongman or heroic archetype while shoving an ice screw in his rectum. Marina Abramović is perhaps the most famous example of a performance artist’s fascination with pain; she’s devised works in which she’s had to climb down a ladder of knives, run headfirst into her then-husband, Ulay, at full speed and fully nude, sit still while visitors slap her and aim loaded handguns in her face, and lean back precariously while a bow and arrow is pointed directly at her heart. Despite the extreme violence inflicted on the body of both performers, Abramović and Barney’s stoicism in the face of this pain is just as much a part of the performance, shielding audiences to its aftereffects. The body is a canvas in that it is utterly void. To be vulnerable is to give some aspect of the show away, to let viewers peek behind the curtain.

It is here where the performance art, secluded within the confines of the gallery walls, can be breached by the collective ideas of the world beyond. Vulnerability is often seen as a weakness. Those in power constantly berate people who can’t “pull themselves up by their bootstraps.” Men are told to man up, lest they give someone ‘the ick.’ When I was young, I was told that my twin brother cried too much whenever he fell over and scraped some part of him. That was a signal to me not to follow his lead. Every time I fell afterwards, I would try to hold it in no matter how agonising it would get. When I fell from my climb, I barely made a peep. I told my girlfriend “it would be fine” and to “keep climbing” as my hand swelled under a bag of ice.

To the layperson, performance art must seem like a pain endurance exercise. If I had gathered a small audience, moved that St Peter’s bouldering wall to a gallery space, and broken my hand there, my work may have been called avant-garde. Instead, it was just an injury and another report filed away in their cabinet.

Artists’ emphasis on stoicism can often have the unintended consequence of poking holes in this thick veneer they have shaded themselves in. By attempting to cover up any vulnerabilities in their performances, one can’t help being reminded of the immense privilege that a lot of them come from. Their ability to access certain resources others can’t makes their dives into serious issues seem quite shallow, as their privilege can shield them from the very real ramifications of their subject matter. Barney, for instance, could dabble in ideas of queerness, bodily boundaries, and intrusion at the tail end of the AIDS epidemic in New York without risking personal consequences.

Meanwhile, artist Millie Brown is known for drinking ludicrous amounts of milk coloured by dye, and vomiting it up on canvases, exploring ideas of “the synergy and separation of mind, body and spirit.” In an interview with The Guardian, Brown suggests that “the struggle makes the performance” and says that she did not intend for the work to reflect eating disorders—an interpretation she sees as a heavily gendered assumption. As Philippa Snow points out, however, “It is difficult to escape the usual associations one might make between attractive, slim young girls and vomiting, making the image more piquant.”

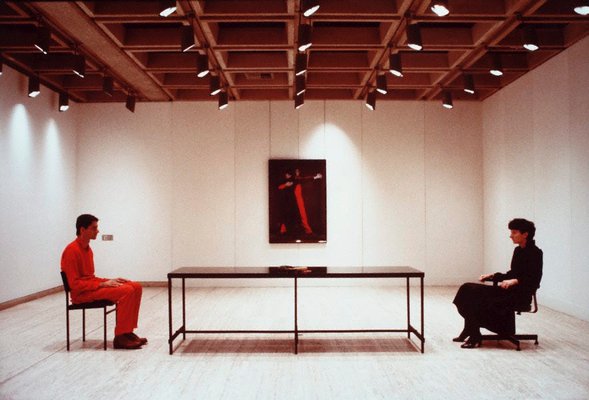

In a similar act of “struggle mak[ing] the performance,” one of Abramović’s many collaborations with Ulay, Nightsea Crossing (1981-86), consisted of “a man and a woman sitting opposite each other in two chairs, motionless, silent[ly] fasting.” For the couple, the work is “mainly about things […] disliked in Western society,” such as inactivity, motionlessness, and fasting. The problem I have with works like these is that these artists can often come away relatively unscathed. For them, the act of fasting or vomiting is just a day’s work, and a way to touch on concepts without fully experiencing them or facing their consequences. As a result, the long process of healing that comes after experiencing these distressing situations is left absent.

Many of these artists, while placing the onus on their own powers of endurance, evade deeper questions about how pain and its interpretation come to be shaped by cultural forces, including gender and race. Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964) takes an approach at once more subtle and incisive. Here, the artist sits complacent on stage as members of the audience are asked to come up and cut pieces of clothing off her body. Her lack of movement or resistance is punctuated by the willingness of audience members to expose her body to the world, an act of sexual violence that highlights the broader issues of assault in our societal milieu.

Ono’s passivity in Cut Piece, however, becomes both an absence and an opening for new possibilities. It presents a conduit to imagining a world without this sexual violence, but also perhaps a world without the need for clothing or a world without views of the body as sexualised itself. The ambiguity of the piece sits in contrast to the work of Abramović which, while aesthetically similar, lacks the nuanced and abstract quality of Ono’s work. For Abramović, the work describes itself; the thing is the thing. Weapons are laid out in Rhythm 0 (1974) for bystanders to use at their discretion. Famously, it doesn’t take long for audiences to slash her clothes off, commit various acts of sexual assault, drink her blood and work a loaded gun into her hand, which triggers a fight amongst the crowd. We come away with the endurance of it, her ability to withstand what was akin to torture and a near-death experience. We are impressed with her stoicism, and mourn the inhumanity of others, but beyond that there is not much to be gleaned.

In the 1970s, the multidisciplinary artist Pope.L began a series of “crawls” in which he would drag himself along the ground of New York City while wearing a business suit. His act pointed out a double standard in American society, one in which the image of an African-American person crawling along the ground was seen as commonplace, but his business-like attire was viewed as being incongruous with his actions, as someone financially successful would not place themselves in such proximity to the ground or be found in such a situation. His crawl along the ground also signalled his “giving up of verticality”—a phrase that points to his refusal of America’s neoliberal myths of upward mobility and trickle-down economics.

There is also a reason why a lot of performance artists are rich, straight, white men. It is often easier for people from these backgrounds to gain access to medical care that has been historically denied to those from more culturally and linguistically diverse or queer backgrounds. It is easier for Barney to explore vague ideas of gender in a very general manner that excludes any personal expressions of gender fluidity, hurting and maiming himself before accessing medical care, than it would be for people whose gender expression veers from accepted norms. Similarly, it was easier for me to be seen at the doctors, have my parents and partner pick me up and drop me off to my various hospital visits, and have all expenses go over my head. These systems have been designed for people like me or Barney, or affluent women like Abramović, who are able to continue finding success in neoliberal systems that reward the already privileged.

* * * *

Beyond the pain the artist experiences themselves, there is catharsis in witnessing these images of grotesque self-annihilation among audiences. Viewers since the silent era have been entranced by imagery meant to perturb. With the emergence of a ‘cinema of attractions,’ early cinema quickly shifted from images of workers leaving factories and babies eating soup towards more extravagant and controversial fare, offering circus-like exhibits in hopes of reeling in members of the public and their “lust of the eyes.”

As film historian Tom Gunning points out, “the scenography of the cinema of attractions is an exhibitionist one […] reach[ing] outwards and confront[ing]” the viewer, whose “curiosity is aroused and fulfilled through a marked encounter, a direct stimulus, a succession of shocks.” Gunning, quoting Augustine, draws attention to the eighteenth-century preoccupation with curiositas, which, in contrast to voluptas (pleasure), “avoids the beautiful and goes after the exact opposite “simply because of the lust to find out and to know.” As such, crowds gathered to attend freak shows, see mangled corpses in morgues open to the public, the “natural curiosities” of London’s Egyptian Hall, or even the “educational actualities” of silent cinema, depicting close ups of cheese mites, spiders, and water fleas. Perhaps our preoccupation with seeing others hurt is merely a part of the pantheon of this pleasure in seeing the unbeautiful. It is much more cathartic and entertaining to witness the shocking act of pain or an insane feat of endurance, rather than the long process of healing and recovery that comes afterwards.

The process of healing is one of capturing time—and time takes time. As the idiom goes, “time heals all wounds.” Healing resists being immediately penetrated by a viewer’s gaze, so it makes sense from a cynical point of view for movies or artists to brush over this process of the human experience. Once the performance is done, the artist moves back behind their curtain to rituals inaccessible to audiences; the second act is a private act, one of healing and recovery. It would be harder to advertise a performance of the long arduous hours spent in waiting rooms, or the hourly exercises to slowly regain control of an appendage. There are no movies in which, after a stunt is performed, we see the action hero go through months of physical therapy. Instead, time is condensed. We cut to the next scene, or a quick montage sequence flies by. Meanwhile, the artist is magically better by the time we see them ready for their next appearance in the gallery.

Once the performance is done, the artist moves back behind their curtain to rituals inaccessible to audiences; the second act is a private act, one of healing and recovery. It would be harder to advertise a performance of the long arduous hours spent in waiting rooms, or the hourly exercises to slowly regain control of an appendage.

—Harry Gay

This is not to say a film or performance can’t explore healing’s duration, it is just that often the examples that penetrate the mainstream forgo this process for the purpose of brevity and easy audience satisfaction. David Gordon Green’s Stronger (2017) is a film depicting the emotional and physical recovery of Jeff Bauman (Jake Gyllenhaal) after surviving the Boston Marathon bombing of 2013. Green’s work packages the process of recovery into a neat two-hour conventional Hollywood melodrama. Surprisingly, given the primacy of film and performance art as visual mediums, more sensitive, patient approaches to the healing process tend to address psychological, rather than bodily, trauma. Ingmar Bergman’s work often broaches this subject, such as in Persona (1966) or Through a Glass Darkly (1961), while Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972) sees psychological scars made manifest through a series of science-fiction phenomena.

Perhaps for accurate depictions of healing one must go beyond mainstream modes of cinematic storytelling. Slow cinema denotes a style of film that attempts to emphasise the passage of time that conventional films often try to obfuscate. Works like Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó (1994) and Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) depict a kind of real time portrait of suffering—be it the cyclical mundane existence of domesticity or the slow collapse and relocation of a town amid the transition to capitalism in post-Soviet occupied Hungary. As Swapnil Dhruv Bose writes of Tarr’s film in particular, “[t]he excruciatingly long takes are a constant reminder of the fact that we cannot edit our way out of our own misery.”

The length of these films lulls me into a kind of trance. Their sense of seeming nothingness makes my mind wander and begin to reflect on this very act of wandering. I start to focus on my breathing, on the placement of my tongue on the roof of my mouth, my discomfort in the seat, the architecture of the cinema, and most importantly, the movement of my body through space and time. The fact that in these hours my body is continuing to exist—the blood continuing to flow through me, the hairs on my head still growing, and the scars on my skin slowly healing.

* * * *

As I continued my exercises and my hand regained some semblance of mobility, it became easier for me to continue my therapy in public spaces. Rather than retreating to the back room at work, I simply did my stretches at the front counter. Instead of hiding my hand when gathering with friends, I put it on the table and moved without fear. My act of healing shifted from a private one to a public one. It became a performance for which my audience grew to include peers and strangers. Onlookers’ comments of “Ooh that looks painful” soon became ones of encouragement and respect as I clenched and unclenched my hand with more ease. My performance became one of healing and dexterity, rather than of pain, and within this process I enacted my own sort of rebellion.

Now when I climb, I wonder what people think of the large scar across my hand. Do they know and silently pontificate as to the process it took for me to get there? I am fully healed, but I still bear those scars of injury. I continue to live out my performance, my extended second act, played out on the perpendicular walls of the bouldering gym.

**********

Harry Gay is a freelance writer and editor, currently undergoing preliminary research for his PhD thesis. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts and Advanced Studies (Honours) at the University of Sydney, and has lectured at various Film Studies conferences around the world. He has a chapter in the upcoming Critical Insights into Science Fiction: Exploring Posthumanism, Alternate Realities, and Cyberculture from Adamas University, to be published by Springer Nature.