Before I knew anything about Việt and Nam, the film’s title had reminded me of an orthographic phenomenon I often thought about. ‘Việt Nam,’ written in my mother tongue, is made up of two different words: ‘Nam’ and ‘Việt.’ Separated—a chasm between them. Then came the English spelling: ‘Vietnam.’ Never mind the loss of accent marks, anglicisation has taken the liberty of wiping out that gap without even the courtesy of asking what this distance could mean, what caused it, and what secrets are buried within. These secrets, perhaps, are what Trương Minh Quý aims to unearth with his soft-spoken and haunting fiction feature debut.

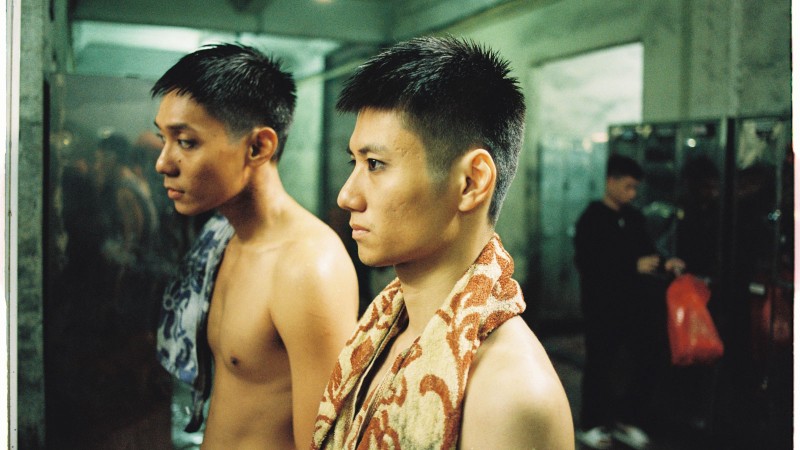

Coal miners Việt and Nam, the film’s co-protagonists and its namesakes, are lovers. Soon, like the two words that make up the name of their fatherland, they will be apart; no more tender glances, no more soft whispers, no more lovemaking under the veil of thousands of glittering stones 1000 metres below ground. Việt’s future is befogged as he awaits Nam’s eventual departure, while Nam takes Việt on a journey into the past in search of his father’s remains.

I sat down with Quý on a Sunday in August. For me: a rainy winter afternoon in Melbourne; for him: a sunny summer morning in Brussels. There was a 16,000-kilometre crow-flight between us, each of us about 8,000, 9,000 kilometres away from our shared country of birth. However, on the screens of our computers, Quý and I were only a few questions and answers apart. Looking to close that distance, I asked him:

Bạch Đăng Tùng: When Nam and Việt are talking about how far apart they would be after Nam’s departure, they use handbreadths to measure that distance on a map, saying it’s only 30 centimetres. In a different scene, the war veteran mentions how soldiers who died in jungles were buried only 90 centimetres deep. Did you intend for there to be a parallel between the closeness of the two lovers and the closeness of the living and the dead?

Trương Minh Quý: While both measured in centimetres, I think those distances have different meanings. In the case of Nam and Việt, the two find solace in telling themselves there will only be a few handbreadths between them. In reality, after Nam’s departure, the two might be thousands of kilometres apart. So, the distance of 30 centimetres is one that defies logic. In contrast, the martyrs’ graves in jungles being 90 centimetres deep is factual. This connection about close distances was not intentional. The distance of 30 centimetres was scripted but the 90-centimetre one was only included after I worked with Lê Viết Tụng, who is a real war veteran, and found out about that historical fact. For me, filmmaking is not about making works that only reflect my original intentions. My process as a filmmaker is not linear. Once I have my screenplay, what I do is break it apart and build it back up with details I pick up from the locations and the actors. Then, during filming, I map out a network of all the pieces of information that could echo one another. And finally, editing is the process of cutting out all the interferences to find the film a form where meaningful connections could surface.

BDT: Việt and Nam is your first fiction feature. Is this filmmaking process the same for your previous works?

TMQ: Before Việt and Nam, I made two other feature films. One is The Tree House (2019), an experimental essay documentary, and The City of Mirrors: A Fictional Biography (2016), which leaned more towards fiction but was not without documentary elements. I also made a few short films here and there. Short filmmaking is different. For me, they are exercises of image-making and editing, rather than complete works. I think they are important because short films are made in the condition of complete freedom. They allow for my thoughts and feelings to have tangible forms, which, after threaded together, reveal a through-line that I can refer to when making my works. In feature films, which are bigger and can be seen as more complete works, when I see the same contemplations that I saw in short films from before, I can tell that they come from a place within myself that I am not conscious of.

BDT: It’s interesting that you mentioned there being a through-line across your works. The Tree House is the only other film of yours I had the chance to see and despite being a documentary, there were a lot of similarities between that film and Việt and Nam. Do you think that those similarities come from what could be defined as your cinematic language?

TMQ: That is an interesting question. Before I try to answer that, could you let me know what you think are the similarities between The Tree House and Việt and Nam?

Quý’s question caught me off guard and, for a few seconds, I just froze. I had only seen The Tree House once, a long time ago. From memory, Quý’s sophomore feature is a meta-documentary narrated by an astronaut from the future on Mars, in a correspondence with his Terran father about the past in Vietnam. Upon revisiting my Letterboxd entry, dated November 1st, 2022, I was reminded of The Tree House being an intimate ethnographic documentary that explores the displacement experienced by some of Vietnam’s ethnic minority groups, as they observe their cultures slowly fading out of existence. I could have said that in both Việt and Nam and The Tree House lies dormant the cultural topography of Vietnam’s history, which, after being rendered through Quý’s gorgeous 16mm film, emerges in human-shaped shadows that cast themselves upon the country’s lush, but adulterated, landscapes. In reality, I spent three minutes stuttering through the words “culture,” “landscape,” and “body” in half-formed sentences before Quý interrupted my babbling with an answer to his own question.

TMQ: I think it is true that Việt and Nam and The Tree House are linked in terms of imagery and concept. With The Tree House, I wanted to define the idea of ‘home’ through different stories from different communities about the houses that they live in, especially their childhood homes. Materialistically, structurally, and spiritually, I wanted to know what home meant, including my own. Việt and Nam also explored the idea of home, albeit not through a literal approach like in The Tree House. In Việt and Nam, home is characterised by a person who is about to leave. Here, home is seen through an emotional lens, through nostalgia and melancholy.

In terms of what could be seen as my language, a documentarian’s gaze is always present. At the beginning of my career, I had to work with heavy budgetary constraints, so the only stories I could tell were akin to documentaries in the sense that I could only work with what was already present for me. So, I decided to start by pointing the camera at the things that were familiar to me, so much so that I would never think to make films about them, such as my family and Buôn Ma Thuột, the city I lived in. These films centred around homosexuality, familial relationships, especially father-son relationships, and childhood memories, which are subjects that still move and intrigue me to this day and are always present in my work, so I guess you could call them part of my cinematic language.

BDT: As you mentioned being a staple in your works, the father-son relationship is a prominent element within Việt and Nam, as half of the film’s plot follows the search for the remains of Nam’s father. The other half, however, focuses on the queer relationship between the titular characters. How do you think these relationships complement each other?

TMQ: While making Việt and Nam, I didn’t necessarily think about whether or not these two relationships complement each other. It just felt right to me to explore these relationships because I can see myself in them. It was habitual. Perhaps there was an intention to create a connection between the father-son relationship and the queer romance, but it hadn’t revealed itself to me at the time of making the film. Retrospectively, as a filmmaker, you begin to see how these elements connect. In Việt and Nam, there is a similar closeness between the relationship of the titular characters’ bodies and that of a father’s and a son’s. After Việt and Nam make love, they talk about how they are both without a father, and how Việt resembles Nam’s father. I think I wanted to draw that connection to embolden a certain strangeness, queerness if you will, in the couple’s intimacy.

Another detail that adds to that strangeness is how much Việt and Nam look like each other. The film actually never explicitly states who Việt is and who Nam is. Their actors, Thanh Hai Pham and Duy Bao Dinh Dao, are each credited as playing both characters. I wanted to maintain that ambiguity where the two characters could be interchangeable or that they could be brothers born of the same father. Of course, if you speak Vietnamese, the distinction between Việt and Nam becomes clearer because you can tell they have different accents. This takes me back to what I said earlier about connections that surface without having been intended. When Vietnamese people see that one character speaks with the Northern accent and the other speaks with the Southern one, they can make the assumption that I intended for that to be a metaphor of some kind. That was not the case. In reality, I wanted for both characters to speak with the Northern accent but during auditioning, only one actor from the pairing that I wanted to cast speaks it. Accents didn’t bother me much, so I just went with these actors.

BDT: I think there are only a few scenes of queer intimacy between Việt and Nam in the film, but they are all delicate and fervent, hence memorable. First is the scene where Nam and Việt make love in the coal mine, with all the minerals shimmering around them as if they are holding onto each other in a starry night sky. Second, and more impassioned in my view, is in the one where Nam removes Việt’s earwax in a barbershop that doubles as a welding shop. How did you go about developing these scenes?

TMQ: There was actually not much calculating that went into writing or filming these scenes. I would describe them as outbursts in the emotional process I put into making Việt and Nam. With the scene in the coal mine, darkness is a powerful filmic texture and the shimmering mineral is a gentle contrast to it. Nam and Việt are making love deep underground in a tight, claustrophobic space, but the imagery of a starry night sky offers them a sense of escapism, which also shows up at the beginning and at the end of the film. The barbershop scene is special. This is the scene where it is made clear that Nam and Việt will be apart, so I want it to come across on an emotional level. The lights dimming down and the sparks flying out of the welding machine create this surrealistic imagery that you often see in a stage production or a musical. For me, it speaks to a kind of magic that comes with love, a kind of love that only Nam and Việt possess, coarse and rough but beautiful all the same.

BDT: I want to ask more specifically about Nam and Việt’s intimacy through their acts of consummation, like when Việt licks blood off Nam’s body after they make love, or when Nam eats Việt’s earwax. Since your film is set in 2001, a different time for gay couples, do these Dionysian actions depict a sense of disgruntlement towards contemporary reactions to queerness?

TMQ: I don’t think that’s necessarily the case. I think Việt and Nam have queer protagonists but the film does not treat queerness as a topic. In today’s world, when one makes a film with gay characters, they have to approach it differently from a film made in 2001, when Việt and Nam is set. I find it quite disappointing that a lot of films made today, especially mainstream films, treat queerness as something heavy and tragic. As a filmmaker, I have to be aware of that and distance myself from it. I want the romantic relationship between Nam and Việt to feel like a kind of universal love, regardless of sexuality, but I also have to understand that the world they live in does not accept their relationship as that kind of universal love. So, the challenge was to find a balance between depicting the reality of the setting and being mindful not to treat queerness as a topic. In Việt and Nam, all the acts of intimacy between the titular characters are done within a space of privacy. This is so that their story does not become dramatised by the contemporary society’s objection to queer relationships. Interestingly, by not mentioning that objection, the film actually is addressing it because that objection is the answer to why Nam and Việt only express their love in private.

I want the romantic relationship between Nam and Việt to feel like a kind of universal love, regardless of sexuality, but I also have to understand that the world they live in does not accept their relationship as that kind of universal love.

—Trương Minh Quý

BDT: Let’s talk more about the setting. Why 2001?

TMQ: I want the characters to be in their twenties and logically, for Nam to have a father who died in the Vietnam-American war, the story needs to take place around the turn of the millennium. Why the year 2001, specifically, is a personal reason. I was eleven years old when I saw the news about the 9/11 attacks on TV. I couldn’t understand much as a pre-teen but I could feel a strange shift in the atmosphere around me. Emotionally, I was strongly affected. Historically, these attacks marked the beginning of an entirely new world, politically and socially. Global conflicts and issues like racism and immigration began to enter the public consciousness. Another reason for the setting to be around that time is in relation to a reference that the film makes to the container lorry incident in 2019. In Việt and Nam, the titular characters pay to be trafficked to a foreign land in a container. That container, for me, symbolises all the tragedies of all emigrants, whether from Vietnam or Africa, or anywhere else. But specifically, with what happened in 2019, I think having such a recent event be referenced in a film set nearly two decades earlier acts as a kind of a consolation for the tragedies faced by those who left.

“If you pay for a VIP package, you will be transported in a private car rather than in a lorry,” says a human trafficker to Nam and a dozen other hopeful migrants. Hearing that line in Việt and Nam, my heart sank to my stomach. ‘There Was No VIP package. Scamming Victims Died at the Hands of Human Traffickers.’ I remember seeing that headline about the container lorry incident in 2019, which was among a myriad of harrowing news reports: ’39 Vietnamese Migrants Died of Suffocation in A Lorry Found in Essex’; ‘A 15-year-old’s Father Learns of His Son’s Death Through Social Media’; ‘A Married Couple Found Dead While Holding Hands,’ etc. Contextualising this incident as part of a greater national history of cataclysm, hope, and loss, Việt and Nam tells a modern fable that is both grand and intimate, provoking me to wonder what drove Quý to take on such an impossible task.

BDT: I feel like at the core of Việt and Nam is this father character, whose absence becomes a symbol of Vietnam’s history for post-war generations. Nam and Việt never had an experience with their fathers, the same way they never experienced the war first-hand, same as you, me, and generations of young Vietnamese people. In that way, Việt and Nam bears the heavy responsibility of providing an answer to the question of what place people like us stand in in the country’s history. What motivated you to lead a cultural anthropology project of such an ambitious scale?

TMQ: I think the motivation comes from a confluence of contemplations about myself and contemplations about the history that I inherit. It begins with the relationship of a father and a child. We ask ourselves if that relationship is only of flesh and blood or if there is more to what links us with our fathers. I realise that it all comes down to this fundamental question of who our ‘father’ is. Việt and Nam interweaves the image of the father into the history of the nation. The relationship young people have with the ‘father’ is a relationship to a national history full of crises, which have not been resolved or discussed adequately in my view. It is an absence, like you say. A loss.

Việt and Nam was never meant to provide any answer to any question. The film actually poses them. What is interesting about these queries is that they do not only apply to the history of Vietnam. Questions about the relationship young people have with the history of the land they stand on are being asked around the world. In former colonial powers, young people are feeling guilt towards the history they feel responsible for. Through observation, we see they form these questions about what their ancestors did and what it means for them to live with the sins of their fathers. Việt and Nam does not ask questions that are so direct but it does try to probe young Vietnamese people to consider the relationship they have with their nation’s history.

The relationship young people have with the ‘father’ is a relationship to a national history full of crises, which have not been resolved or discussed adequately in my view. It is an absence, like you say. A loss.

—Trương Minh Quý

I do agree that the film is ambitious, almost irrationally so. It tries to encompass all the discourses there could be about Vietnam. The title Việt and Nam can attest to that intention. The film is my artistic manifesto, to establish a new ‘gaze,’ a new frame of thinking that can set myself free from the West’s expectations of a post-war story.

My mind clung to that question Quý had posed, of who my ‘father’ was. My father was a soldier for the National Liberation Front during the Vietnam-American war, just like Nam’s father was in the film. Unlike Nam’s, though, my father survived. “This year marks the 50th anniversary of the battle he fought in,” my mother had told me over the phone the day before. I thought about how poetic it was that while talking to Quý about a film where the characters visit an old battlefield to look for ‘the father,’ my father was revisiting his old battlefield in Quảng Nam to commemorate his former comrades. And then, I thought about my mother.

BDT: There is something I find interesting about the imagery of the ocean in Việt and Nam. The first time we see it, Việt calls it a graveyard for the shellfish. Then, we hear the mother character sing a lullaby over the image of the waves. Finally, Nam and Việt hold each other nakedly in a container floating in the sea, while telling each other a bedtime story. Another detail is how Nam lies in the foetal position during a training module for the trafficking operation. All these details evoke the imagery of the ocean being both a tomb and a mother’s womb. We talked about the father—what is the significance of the mother to the history that Việt and Nam discusses?

TMQ: The mother is important, too. The character of the mother in Việt and Nam, Mrs. Hoa, came from a personal connection to my mother in real life. In my family, my mother is the only woman and similarly, the mother in the film is the only woman in the main cast. I think that in many families of my generation, the fathers are always away and so we grow up with our mothers at home. I think the relationships that Mrs. Hoa has with the characters in the film, mainly to her son, highlight the absence of the father. There is that strangeness in the intimacy between Mrs. Hoa and Nam, in a way, like when she says her husband takes after her son while it is supposed to be the other way around. Nam searches for his father through the memories his mother has of him.

Meanwhile, Mr. Ba, the veteran, shares with Mrs. Hoa the wartime memories of her husband in an attempt to reconnect with his fallen comrade. The characters around her look for ‘the father’ within her because she is the one closest to him, but she is looking for him in the men that surround her. Then comes the separation. Mrs. Hoa is the one left behind by both her husband and her son, which I find to be a rhyme that history has, where similar events happen one after another. As for the image of the ocean, I just thought of it as the echoes of the final scene throughout the film. The image of the mother’s womb is an interesting interpretation but I never considered it. These were things that came from an emotional space when making the film and I didn’t necessarily have an intention for them. What I mainly focused on was the image of the underground, which could be called a tomb, like you say. The characters being coal miners can be understood as a metaphor for looking for history as they dig up ancient minerals and fossils in the heart of the earth.

BDT: Trong Lòng Đất (In the Heart of the Earth) is the Vietnamese title of the film, which ended up never being used as the film was banned in Vietnam. There is something I find very poetic about this situation. The final moments of Việt and Nam are of the titular characters telling each other The Legend of Mai An Tiêm. Like Việt and Nam, Mai An Tiêm was exiled. However, towards the end of that story, Mai An Tiêm was called back to the kingdom. Do you think Việt and Nam will share that fate?

TMQ: It could be a matter of waiting but I do not want to exhaust my time and emotions thinking about whether my film will be released in Vietnam or not. Of course, I do not agree with the basis on which they are banning my work, which is that they consider the picture I paint of Vietnam to be “negative” and “gloomy.” A lot of Vietnamese citizens overseas saw the film and told me Vietnam was beautiful in my work, saying that it reminded them of home. I find it very disappointing that the film could not be screened in my country of birth but there is nothing I could do to change the minds of the censorship board. They have their job to do and I have mine. They will go back to censoring movies and I will go back to making them. Looking on the bright side, however, Vietnam has become more open-minded than before when it comes to receiving arthouse cinema so I am hopeful that more films by Vietnamese auteurs can be released in their country of birth.

BDT: I hope so, too.

* * * *

With our shared sentiment of optimism, the talk between Quý and I came to a close. Right before it ended, I looked within every corner of my mind to find another question to ask Quý. A few more half-formed sentences later, Quý assured me that I did not have to force more questions if I had none left. Defeatedly, I nodded. Quý and I went back to being 16000 kilometres apart, each of us 8000, 9000 kilometres from our shared country of birth.

Getting off the phone with Quý, I called my father. He must be in Quảng Nam, I thought, with his former comrades from five decades ago. For a split second, I forgot what his face looked like. Then, I saw him, his image blurred by the poor internet connection between us. He was wearing his green uniform, with medals on his chest and Vietnam’s national flag just above where his heart is. With his familiar raspy voice, for the fifth year in a row, my father asked me if I would get a day off on the second of September. I told him what I had told him the last four years, that Vietnam’s Independence Day is not celebrated in Australia. The call would soon disconnect.

Note: this interview has been translated by the author, and it has been edited for length and clarity.

Việt and Nam is screening again on the 25th of August at this year’s Melbourne International Film Festival.

**********

Đăng Tùng Bạch is a Naarm-based filmmaker from Hanoi, Vietnam. Short films he directed have been screened in Vietnam and Australia, as well as in Europe. He writes about films to understand the stories they hold, hoping he can tell stories of his own one day.