I.

In the nine short films of Stephen Cummins, human bodies are in constant motion. Far from being fixed, immutable objects, they evade the comfort of absolute definition, suspended in an unending negotiation within and against convention. Figures embrace, kiss, spin, and dance in ways that articulate other, queer forms of being in the world. After premiering at the Mardi Gras Film Festival during Sydney WorldPride in February 2023, these restored pieces of little-seen Australian queer cinema—made between 1984 and 1995 on Super 8, 16mm, 35mm, and video—will screen as part of the Melbourne International Film Festival’s program on the 30th anniversary of Cummins’ premature death at the age of 34 from HIV-related lymphoma.

II.

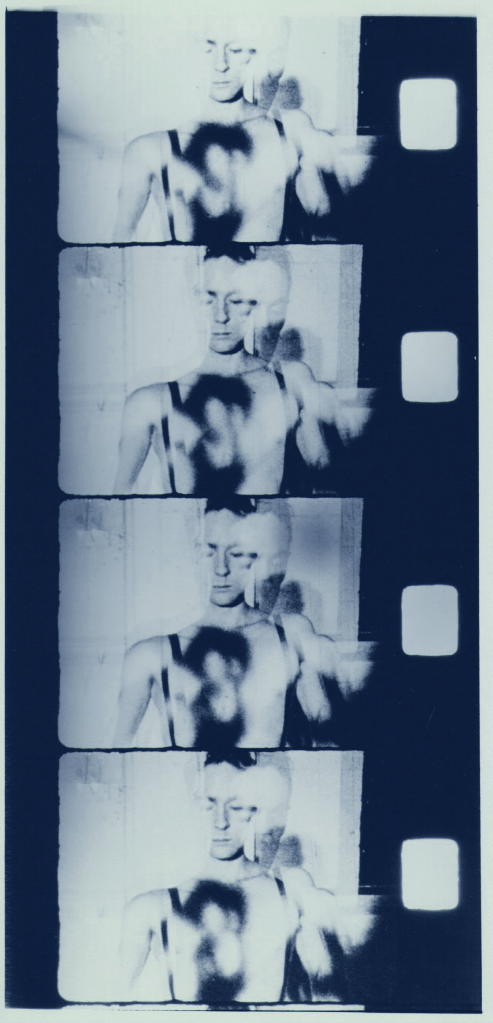

In the trilogy of student films Cummins completed while studying at Sydney College of the Arts—Breathbeat (1984), Blue Movie (1985), and Deadpan (1985)—on-screen bodies are constantly elusive. They appear, disappear, appear again, remain out of focus, and fragment into pieces. In Blue Movie, the monochromatic image of a young dancer is proliferated through multiple exposures, confounding where the boundaries of his body begin and end. Over the course of a slow zoom, shadows of moving hands are cast onto his chest and torso. The soundscape is equally polyphonic: a slow melodic beat, sounds of scraping and crumpling, and clusters of whispers—“impetus,” “technique,” “syncopation”—flickering in and out of legibility, volumes undulating.

We enter Breathbeat through a looping, industrial-inflected soundtrack played over a dark screen. A volley of cuts splinter the body through a sequence of extreme close-ups, flickering beneath the vertical scratch marks of Super 8 film: a flexed arm, dark hair clustered in an armpit or around a nipple, a pierced lobe, the gaping canal of an ear, a swallowing throat. But these are only the recognisable ones—often, the dermal surfaces turn sculptural, distilled into a colour, a shape, or a line that splits the screen into two tones. Breathbeat shares the queer intimacy of Andy Warhol’s Sleep (1963), in which the artist filmed in looped close-ups the sleeping body of his then-lover, the poet John Giorno. Both films queer the body both as an object of gay desire and of defamiliarization, turning it into an alien landscape. But there is something more restless in Breathbeat than in Warhol’s glacial, five-hour provocation. According to Cummins’ friend and collaborator Simon Hunt, Cummins’ early films record the filmmaker’s own unresolved sexuality, emerging from an embodied experience of liminality and indeterminacy.

In Deadpan, the body is even more evasive, an almost spectral presence that haunts an otherwise unoccupied studio. A continuous circular pan glides past white photographic backdrop sheets, a classical style plinth, smoke rising from cigarettes in a tray, and an armchair rocking back and forth. A comparably structural treatment of a single room is found in Chantal Akerman’s Le chambre (1972), in its anti-clockwise pans of a New York City apartment. Yet while Akerman is seen in her bed upon each rotation, the camera in Deadpan intermittently catches a figure walking toward it, each time from a different location in the room. The pan gradually increases in speed as the figure inches unnervingly closer on each appearance until finally their face, obscured by shadow, fills the frame.

III.

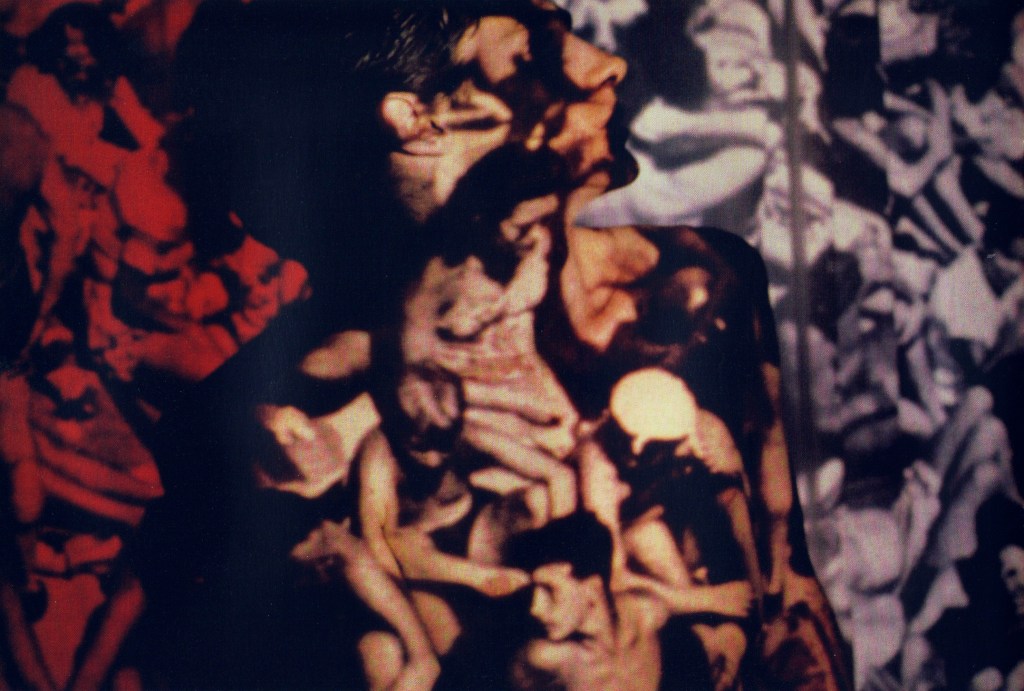

In 1952, the photographer J. R. Eyerman captured a now-famous image of audience members viewing the premiere of the first 3D colour feature, Bwana Devil, at the Paramount Theatre in Hollywood. This image, now primarily associated with the cover of the 1983 edition of French philosopher Guy Debord’s essay The Society of the Spectacle (1967), appears out of focus in the first shot of Cummins’ Le Corps Imagé (1987). Panning down, it is revealed that this is in fact a projected image; the dark 3D glasses are being worn not only by the cinemagoers in the photograph, but by the people onto whom it is projected.

Through a series of images projected onto naked bodies, Le Corps Imagé creates an interface between light and flesh. A photograph of a football player performing a heel flick travels between two torsos gently swaying like kelp in an ocean current, the image warped, deconstructed and reassembled as it is exchanged between them. A portrait twists and curves atop the skin of two bodies rolling into each other beneath creased silken material. Both the bodies—aglow with new, luminescent skin—and the projected photographs liquify, bend, and flex, melting into strange shapes.

Their combination births an abstract amalgamation, making strange both image and body to reveal the plasticity of both. Differently sexed bodies merge and mingle: a male athlete, hands on hips, ripples slowly over a rotating woman in a similar pose. The projected image comes to contain not only its own content, but the incongruous shape of a bottom, a chest, a belly. Another woman bears the image of a masculine classical Greek sculpture, their physical differences coexisting on her skin before she pulls a sheet over herself, metamorphosing into another form, as the sculpture is made near-opaque by the green fabric beneath. More than a passive canvas, the body’s surface is a site and agent of malleability.

For Debord, modernity is defined by the hegemony of the spectacular image, whereby representation and mediation eclipse direct experience. In Le Corps Imagé (literally ‘the imaged body’), bodies are constituted by cultural representations whilst also forming the material of these representations; where one ends and the other begins becomes indistinguishable.

IV.

The body implies mortality, vulnerability, agency: the skin and the flesh expose us to the gaze of others but also to touch and to violence.

– Judith Butler, Undoing Gender

A passionate encounter between two lovers in a lift is abruptly interrupted by a large group filing in one-by-one through its manual, scissor-gate door. Their gazes are scrutinising, judgemental, dubious. With Elevation (1989), Cummins’ work began to experiment with narrative form and the more explicitly political concern of gay visibility in public spaces. This development coincided with the growing politicisation of queer culture: in New South Wales, sex between men had only been decriminalised in 1984, when Cummins was 23 years old. At the same time, he and his collaborators were combatting widespread stigma to receive funding from the Australian Film Commission ahead of lagging mainstream visibility, which did not arrive until the 1990s with The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert and The Sum of Us (both 1994).

As the two men stand apart amongst the gathered strangers, there is a palpable sense of the fleeting contingencies shaping queer life, of compulsory heterosexuality pushing queer sexualities into the margins, where it found expression in the necessarily imaginative use of spaces like restaurants, public toilets, or parks for pockets of intimacy. The lift is another: the sound of its hydraulics and flashes of light, which periodically illuminate the small, rectangular space as it passes between floors, are a constant reminder of its precarious privacy.

After the men have resumed their encounter in the emptied lift, there is a cut to the couple’s bedroom, where a group of admirers with drinks in hand clap and grin as they gather around a white-sheeted double bed. The scene is like a modern bedding ceremony, a ritual in European cultures wherein a newlywed couple were put to bed in front of family and friends. These ceremonies, which sometimes included actually witnessing the first sexual encounter, were believed in 16thcentury England to bestow legitimacy upon the union and the community’s investment in it. In Elevation, it is playfully reimagined as a triumphant, utopian celebration of gay sex. The men are showered in champagne, released from the pressure of the bottle, as their wet, naked bodies roll together on the sheets.

V.

It matters to get lost in dance or to use dance to get lost: lost from the evidentiary logic of heterosexuality.

– José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity

Resonance (1991) opens with a reverb-heavy echo chamber of shoes on concrete, fists colliding with skin, winded breathing, and inaudible insults. A white shirt is ripped, a bottle smashed. Eyes burn with hatred in stark black-and-white. Told largely through point-of-view shots, this visceral impression of homophobic violence—based on an incident in Cummins’ own life—resounds through the film. The victim is saved by a man who becomes his teacher, dance partner, and lover, who runs a class where gesture is finessed into precise, functional movements of self-defence. Later, we glimpse the life of one of the attackers, whose aggressive comportment, moulded by a congealment of homophobia and misogyny, constantly threatens to boil over into confrontation. The camera lingers in slow motion on his taut arms as they pull his girlfriend into a possessive embrace. With the film’s only dialogue washed out in cascading reverb, gesture supersedes language as its central communicative device, thrumming with an energy that oscillates between violence and care, ownership and cooperation.

This economy of touch culminates in a surreal pas de deux inside a boxing ring. The lovers stand at opposite corners, rehearsing moves alone. The match begins in fast cuts and flying fists before transforming, suddenly, into a dance. A fluid camera circles the ring as their movements turn from jagged and combative to flowy, delicate, and open. Here, dance is corporeal healing, a means of reclaiming the agency stolen in the bashing. Choreographed and performed to minor-key strings by Chad Courtney and Mathew Bergan, the contact between the two is collaborative rather than contentious; as they share and transfer their weight, they claim the body as a medium of communication, intimacy, and mutuality. I am reminded of the cathartic denouement of Claire Denis’ Beau Travail (1999), released eight years later. In a deserted night club, Denis Lavant’s repressed French Foreign Legion sergeant rechannels the uniformity of countless training regimens into a manic frenzy of movement, shaking loose insidious strictures of imperial masculinity to Corona’s pulsing Eurodance hit ‘The Rhythm of the Night.’

In the later part of Cummins’ life, the word ‘queer’ was teetering on the cusp of reclamation, with its harmful past communally regenerated into an umbrella of positive, non-conformist political identities. Resonance was the film that took him to the Sundance Film Festival in 1992, where he participated in the famous “Barbed-Wire Kisses” panel alongside Todd Haynes, Derek Jarman, Jennie Livingston, Gregg Araki, and Isaac Julien, among others. The panel inspired moderator B. Ruby Rich to coin the term ‘New Queer Cinema’ in reference to the freshly politicised style of independent queer filmmaking on the rise. The following year, Cummins furthered his advocacy for the form and investment in the communities working within it by playing a central role in the establishment of Queer Screen, which sought to place Gadigal/Sydney’s Mardi Gras Film Festival—then operated through a commercial cinema chain—in community hands, acting as both a genesis and custodian for Australian queer film and video.

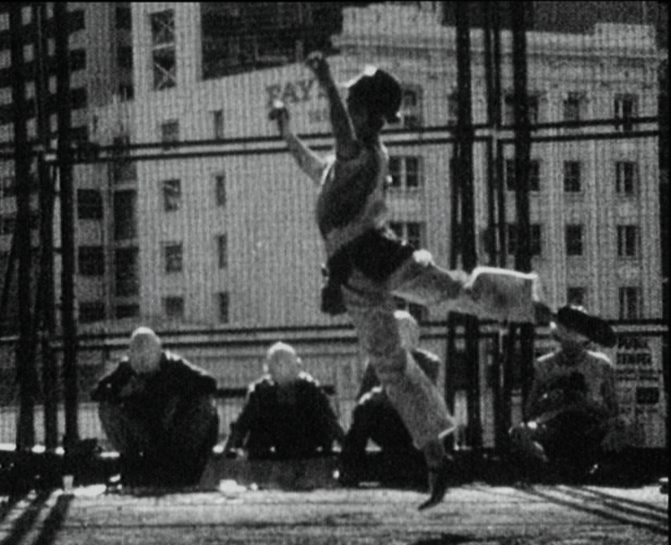

In Cummins’ film for SBS Television, Body Corporate (1993), a builder in heels dances atop a construction site, his shoes scraping across concrete in circular shapes. The soundscape invokes the site’s ambience through running water, the crackle of a lit cigarette, liquid in a can, and audio of advertisements for radio programs exploring music from film, television, and musicals. In this stiflingly hyper-masculine work environment, the builder’s graceful, balletic articulations are taxing forms of deviance; he is puffed out, cooling his face with a fan, and gulping down soft drink. A jackhammer is heard off-screen; a megaphone-filtered voice begins to scrutinise the individuality of the builder’s movements. Looking down from a higher platform, his boss’s voice stands in for the often-panoptic forces of gender normativity, jeering, “where’s your body? […] you’re dancing like a depressed homosexual. What’s the title of this ghastly performance, anyway?”

For the late Cuban-American scholar José Esteban Muñoz, queerness is a well of optimism that pushes past the “prison house” of the present to “the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality.” First present in Blue Movie, dance becomes in Cummins’ later films an extension of the queer expressive possibilities of the body—a continuation of his collaborative theatrical work with various dance and performance groups during his student days. Amid the profound impact the AIDS crisis was having on the health and societal perception of Gadigal/Sydney’s gay communities, dance in Resonance and Body Corporate is the warm horizon Muñoz describes: a means for the body to strain against the norms imposed upon it and reach for new, queer forms of bodily articulation.

VI.

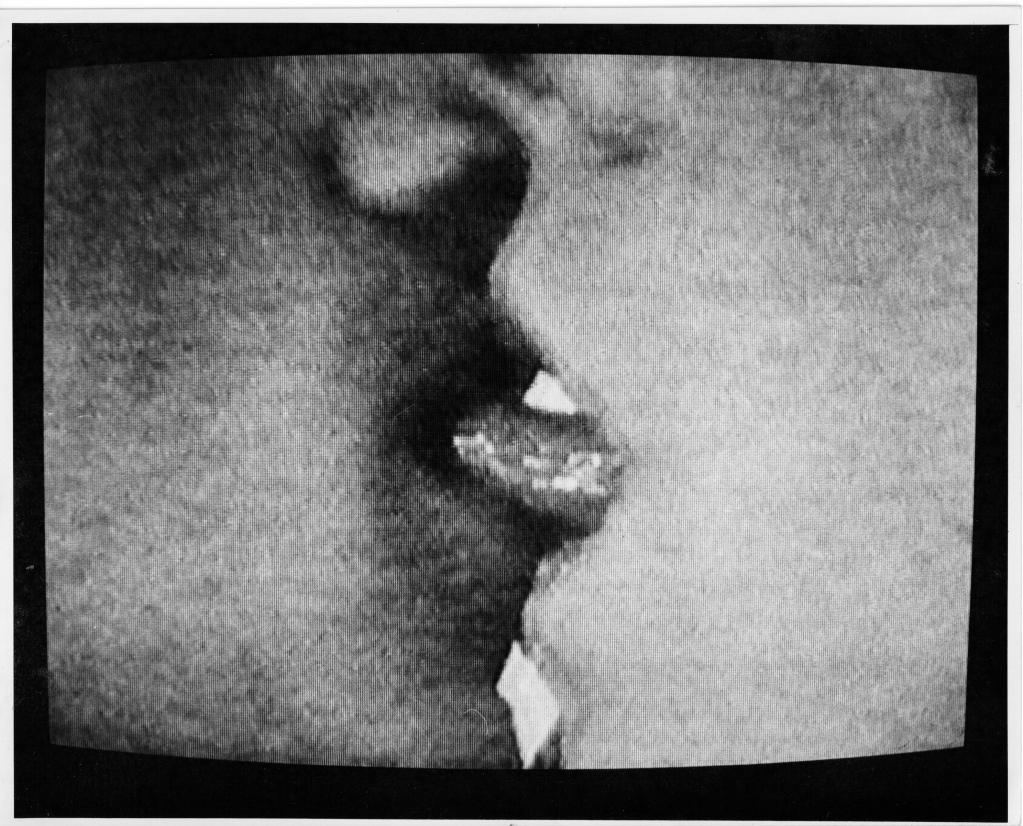

Cummins’ later work also challenged censorship rulings through queer appropriations of the mannerisms and aesthetics of commercial television. As part of a group project in which filmmakers made 30-second films to be screened during commercial breaks on late-night Perth television, Cummins made Taste the Difference (1989), a faux advertisement which begins with an extreme close-up of two people kissing, the camera fixated on their dancing tongues. Zooming out, two men are revealed (Chris Ryan and Herb Robertson) and the phrase “taste the difference” appears on-screen, a line easily readable as an advertising slogan (Google reveals that there is now a kitchenware brand of the same name stocked at Bunnings which sells gourmet pots and air fryers). With flat, reverent synth waves, the film appropriates the aggressively attractive approach of advertising in an unapologetically direct display of gay eroticism. Though approved by the federal advertising standards body, the film was banned by the television station manager, who objected to the graphic nature of the kiss, apparently irrespective of both kissers being men. But Hunt suspects that the fresh wave of homophobia stirred up by the AIDS crisis was the more likely reason behind its prohibition.

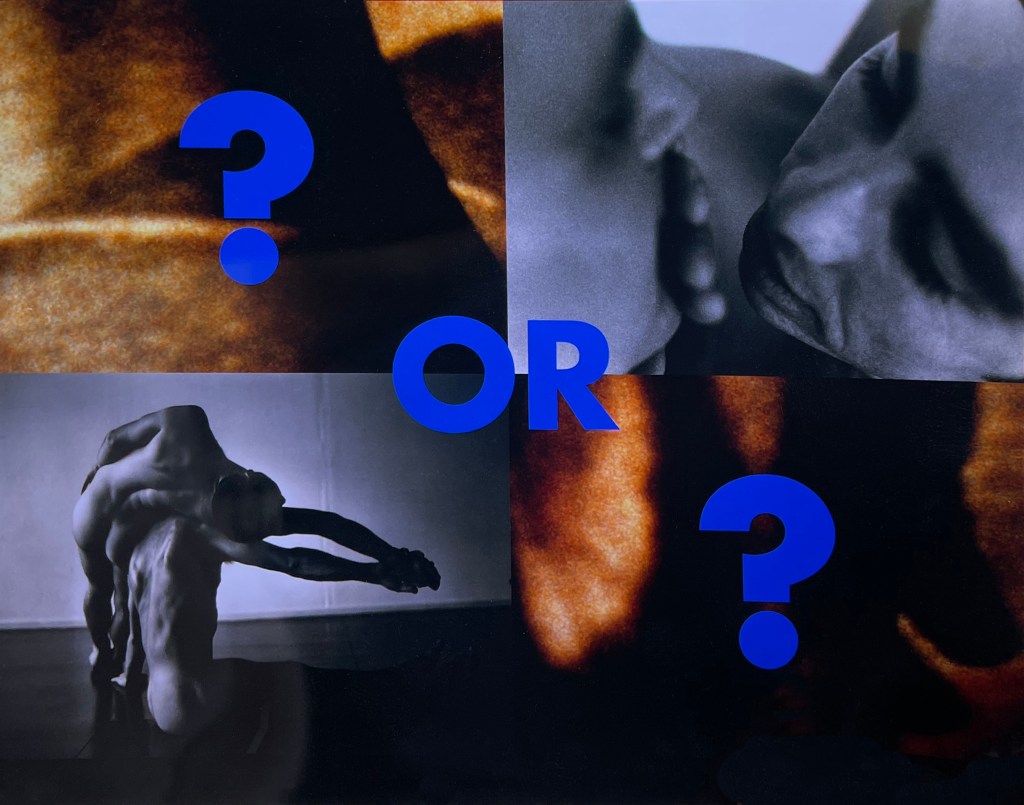

Though the filmmaker’s final work, The HIV Game Show (1995), was never screened, it made more headway on the front of battling anti-queer censorship. Completed by Cummins’ collaborators after his death, the film was the product of a project wherein filmmakers made one-minute films with four images, to be shown in cinemas during slide-based advertising sequences. Composed of four composite still images, the film constructs a game show through audio where all contestants are HIV-positive. In a biting parody of the still-contemporary issues of gay censorship, stigmatisation and the cost of living, the off-screen contestants are asked why the image of two men kissing from Taste the Difference was banned from TV (“they said the kiss itself was too explicit”) and how to get by on a “$200 pension, but spend $300 on food, rent and those pricey pills and potions,” to which the correct answer is “I don’t know.” Should they win, contestants graduate to an experimental drug trial. They are invited to be “a human guinea pig on a dangerous unknown drug, or a sugar placebo pill” (but, as the host jovially exclaims, they don’t actually have a choice; it is made for them). The HIV Game Show was banned by the cinema advertising company, though the dispute over its banning ultimately led to the word ‘homosexuality’ being struck from the ‘adult themes’ list in Australian censorship guidelines.

VII.

…the body is not understood as a static and accomplished fact, but as […] a mode of becoming that, in becoming otherwise, exceeds the norm, reworks the norm, and makes us see how realities to which we thought we were confined are not written in stone.

– Judith Butler, Undoing Gender

Cummins’ films delicately capture the pleasures and perils of inhabiting a queer body, particularly those belonging to white gay men. Whilst grappling with the contradictions of corporeal affordances—bodies inflict pain, heal, are imprisoned by oppressive norms and strain against them—they negotiate the challenges of queer visibility by putting their faith in the generative power of gesture and motion. Prodding at heteronormativity’s porous foundations, Cummins’ films frame bodies in truly queer terms; as fluid, unstable, and mutable—negotiated through an unending process of hopeful creation.

The Stephen Cummins Retrospective screens at the Melbourne International Film Festival on the 23rd of August.

**********

Alex Williams is a PhD student, writer, and editor living on Wurundjeri Country. Their doctoral research investigates corporeal vulnerability in contemporary slow cinema. They are co-coordinator of the community engagement program Screening Ideas and a committee member of the Melbourne Cinémathèque.