In Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities (1972), the explorer Marco Polo recounts to Kublai Khan the sites of his latest voyages—each an architecture of illusion that slips from the emperor’s hungry grasp. Among them is Octavia, a “spider-web city” of ropes and hammocks slung between two great mountains; Eusapia, an underground haven for the pondering dead; and Leonia, which, treating its street cleaners “like angels,” is completely renewed with each passing day. “In fact, all of these cities described are just describing Venice, where they are,” explains Audrey Lam, remembering Calvino’s tales as an early touchstone for her nimble first feature, Us and the Night. In the film, however, it is a single building—a library—that nests infinite worlds. Here, aisles form mazes, margins are inscribed with codes, and empty shelves resemble the skeletons of ancient beasts.

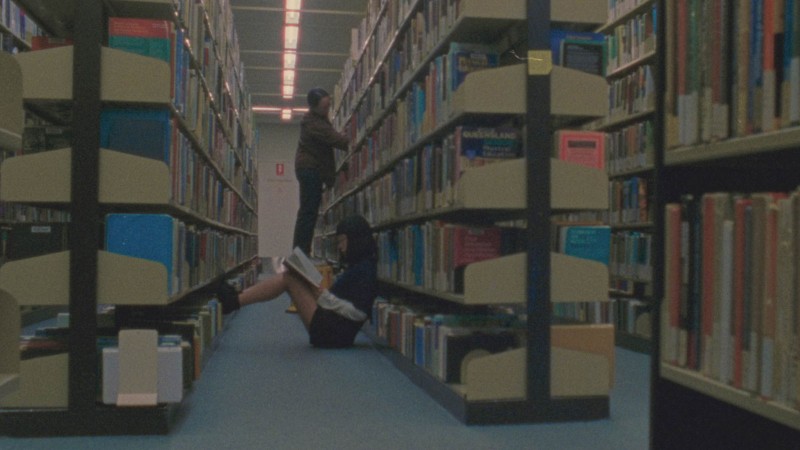

The film is “always in the library and always beyond the library,” says Lam. “It’s a story about stories.” Captured on luminous 16mm over the course of ten years in the University of Queensland library, where Lam used to work, the space appears to us through the memories and motions of two nocturnal wanderers, on a seemingly unending night in the aftermath of a storm. While Lam’s camera roams, paces, and flits between the books’ bounties of images, library attendants Umi and Xiao (played by Umi Ishihara and Xiao Deng, both artists and friends of the director) patiently pursue its enigmas. As they recall fables and dreams in stretches of spellbinding narration, and Umi awaits her twenty-first birthday, on which Xiao promises to share the library’s deepest secret with her, Lam draws out a portrait of tender companionship rooted in perennial curiosity.

Even before beginning work on the film, Lam was compelled by the doubleness of the library, as a “grid-like structure” whose carefully delineated matrix nevertheless houses a wild, utopian charge. “This main library I always thought was really evocative—like really banal, but also quite specific to this time of universities, and what the libraries were.” The library, “still furnished in the seventies layout,” for Lam evokes the idealism of an all-too-brief period of free tertiary education in Australia, with its retro architecture becoming an ebullient playground for Lam and her actors alike. “It’s like the […] perfect place to do dolly movements, because it’s carpeted, you’ve got the [wheeling] chairs, there’s a million paths you can go down.” Graceful disorder reigns as Umi—a balletic, quietly impish presence—runs, crawls, and dances her way through the library, which, Lam says, laughing, “was open the whole time.”

Lam describes the story arc of Us and the Night as something that revealed itself over time. “I always had the library, there were these things I was interested in, but it was just about how to shape it.” The film opens with the ambience of a fresh storm, which reminds Xiao of when the library she used to work in with Umi had flooded. “There was a storm in Brisbane just before we were about to film, and it was amazing because everything was so dry that these trees were completely uprooted,” says Lam, who features the debris in rare moments of blue-black exterior footage. There were also Lam’s evolving habits as a lifelong reader. While she alludes to the slow span of the film’s creation as an outcome of a paltry funding landscape, this duration also lent itself to a bowerbird-like process of gathering referents, who in the end ranged from Robert Louis Stevenson to Lydia Davis and Anne Carson.

I kind of wanted the film to be this period piece and a science-fiction, and just like a documentary.

—Audrey Lam

Beneath its abundance, Lam’s film is also disturbed by an undercurrent of grief, which reminds us not only of the wreckage of public education’s halcyon days, but of the digital age’s unmet revolutionary promises. Umi’s sing-song meditations frequently return to islands and isolation, while water-damaged stacks pile high around her. “The film is as much about the contraction—the incoming age of the internet and so forth,” shares the director. “When I first started working in the library in the early 2000s, this university library, it was at this time of digitisation, or the ‘information superhighway.’” Umi and Xiao wear uniforms embroidered with ‘Cybrary’—the name that the University of Queensland Library took up during this era of fanatical rebranding. “I was one of the staff that just ended up working in all the different branches, which all gradually closed down,” Lam reflects; “the Biological Sciences library stopped having books, it became a digital […] study space, and same with the Physical Sciences and Engineering Library, the Economics Library.” “I kind of wanted the film to be this period piece and a science-fiction, and just like a documentary.”

Despite its near-devotional attention to the library’s textures and forms, the film also effects a floating sensation, often feeling untimely and adrift. A library, after all, is a transitory zone between the present, browsing body and the historical record, between material and subconscious realms. This dreamy aura is only heightened by the muggy glow and nebulous grain of Lam’s film stock. A long-time member of Melbourne’s Artist Film Workshop, a collective which specialises in making and screening 16mm films, she couldn’t imagine making the film using any other medium. Preferring playful inquiry to polish, Lam didn’t “want the film to be a really skilful, accomplished work.” “It’s not perfectly filmed or recorded, and I think that ends up being part of it. Like I don’t think I set out to do this kind of clunky thing, but in the end you just work intuitively,” she says. Working with sound artists Mikey Young—who “comes from this sort of punk background”—and Tim Jenkins, Lam also brought this ethos to the film’s atmospheric soundscapes, which often flush the library with the crinkle of rain and tides.

As another well of inspiration, Lam speaks eagerly of Calvino’s relationship to reading (“he spent more of his life reading other people’s writing than writing his own”) and with his English translator, William Weaver, who quickly discovered that the author sought “to rewrite his book through translation, because he kept having these, ‘Oh, no I don’t think the English word is this, I think it’s that’ [moments], and the word was no longer close to that Italian word.” Like Calvino, Lam approaches language with a merciless wonder—“pilfering” it, shaping and reshaping it like Play-Doh. Aisles become isles; spines belong to books and bodies; letters are both simple shapes and divine messages. “I like this idea of a film that is being written and rewritten and rewritten all the time,” she muses.

Us and the Night screens at the Melbourne International Film Festival on the 12th, 18th, and 25th of August.

**********

Indigo Bailey is a Tasmanian writer and editor living in Naarm/Melbourne. In 2023, she received the Island Nonfiction Prize for an essay about rain sound. She has written for Island Magazine, The Guardian, Voiceworks, and Kill Your Darlings, among other publications.