This year, Rough Cut is partnering with the Melbourne Cinémathèque to bring you new features and reflections on picks from their annual program. First up is L’amour fou (1969)—a form-rattling, intimate epic directed by the French New Wave’s most ludic visionary, Jacques Rivette. Sentenced to obscurity after its original 35mm materials were lost to a fire in 1973, L’amour fou will screen in its digitally-resurrected glory at the Cinémathèque this Wednesday, July 31. Rounding out a complete retrospective of the similarly elusive Frenchman Jean Eustache, it will be preceded by Eustache’s 1982 short film Les photos d’Alix—a phantasmic drift through the portfolio of Canadian photographer Alix Cléo Roubaud, which begets more questions about art, exposure, and disappearance.

* * * *

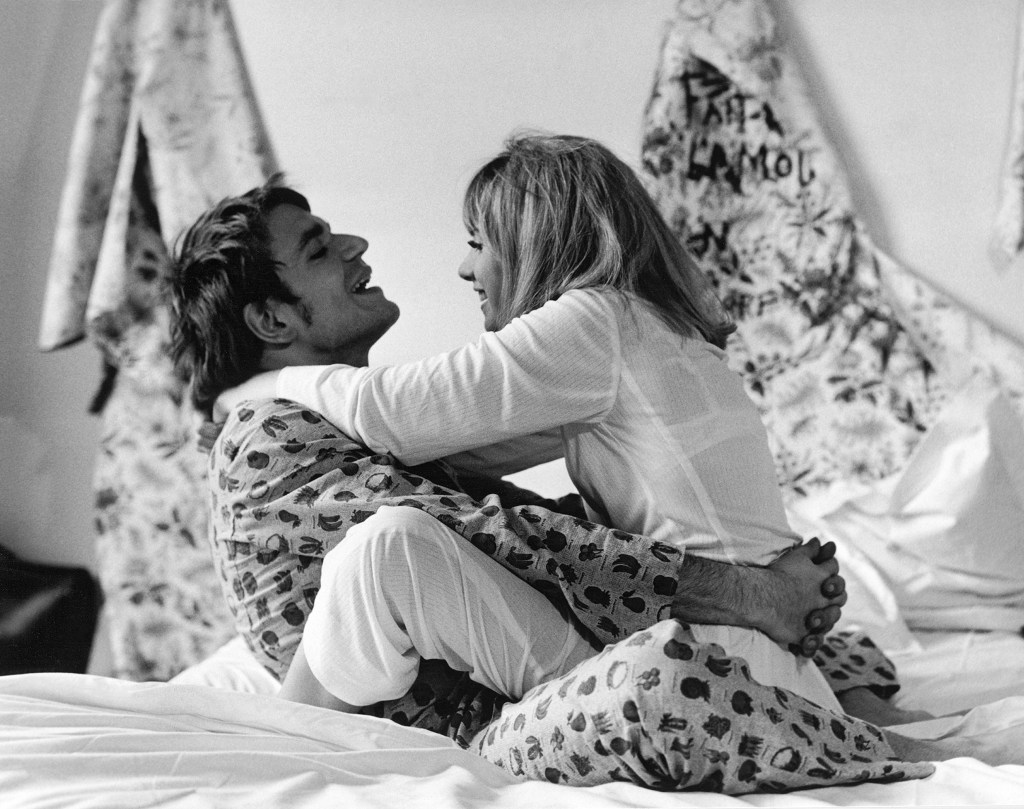

L’amour fou is a raucous mise-en-abyme of love’s anarchies and ecstasies. For over four hours, we witness the disintegration of a married couple, theatre director Sébastien (Jean-Pierre Kalfon) and actress Claire (repeated Rivette co-conspirator Bulle Ogier), who has just been exiled from her role in his production of Jean Racine’s Andromaque. Sébastien continues to rehearse before a documentary television crew (with his wife’s onstage replacement, sultry ex-flame Marta [Josée Destoop]), while Claire nurses suspicions about his fidelity. The pair—at once obsessed lovebirds, twin bandits, and remote strangers—are drawn apart and together in escalating rituals of paranoid play. On some days, they torment one another with silence, interrogation, and self-destructive performances. On others, they hole up in bed, jostling and doting, wearing pyjamas and eating stockpiled yoghurt, rarely not touching.

Rivette’s films habitually rotate on parallel poles of order and chaos, which are always at risk of toppling into one another. In Céline and Julie Go Boating (1974), two heroines pursue undefined spectres through a self-reproducing, psychedelic dream maze. Le Pont du Nord (1981), which was co-penned by and stars Ogier alongside her daughter Pascale, has a claustrophobic ex-con and a roving loner discover a game board that seems to map the secrets of Paris, but in reality only teases the city’s unknowability. Meanwhile, the expansive serial Out 1: Noli Me Tangere (1971) sees thirteen oddballs swarm and overlap as part of an atmospheric conspiracy—a scattered assortment of notes and gestures fated to remain unsolved. Arbitrary but often deathly serious in consequence, odd logics are introduced as if only for the pleasure of watching them combust, as they dovetail with ordinary coincidences and mistakes, and cede, finally, to the sensuous and the sublime.

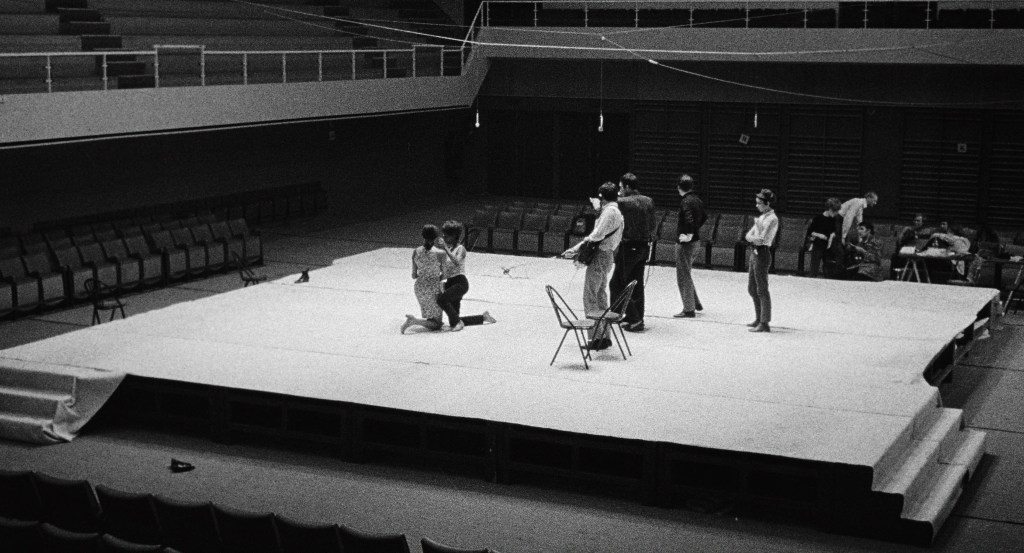

Like the surrealist fantasias that followed it, L’amour fou unspools its own logos from within. Its narrative and aesthetic approach stands out, however, in its remarkable ambition and simplicity, infused as it is with both the tactile minimalism of the theatre and the shaky ephemerality of the cinema. In a proto-mockumentary style, the fraught rehearsal of Andromaque is shot in high-contrast, black-and-white 16mm by real-life television director André S. Labarthe, whose onscreen persona seeks to create a behind-the-scenes portrait by interviewing Sébastien and his actors. Meanwhile, Sébastien and Claire’s private tumult appears in wispy 35mm, their apartment often overexposed to a near-bleached whiteness. Instead of offering a naturalistic backbone to the stage’s artifice, the domestic in L’amour fou—made, notably, in the precarious wake of France’s 1968 cultural revolution—is an unstable construction of its own, its façade only a breath away from ruin.

For Rivette, cinema’s animus was a collective life force, with a sacred capacity to belong to everyone and no one. In contrast with bombastic contemporaries like Jean-Luc Godard, Rivette was an elusive cultural figure who, after a stint as editor of Cahiers du cinéma, disavowed much of his own criticism and spoke sparingly of his work. He often bristled at the tenets of auteur theory that the Cahiers school had gestated and clung onto since the 1960s. Following his more conventionally realist, script-bound two features, Paris Belongs to Us (1961) and The Nun (1966), L’amour fou marked the first of Rivette’s more openly woven, improvisational experiments, heralding his decades-long interest in pursuing deep collaborations with actors, writers, even musicians. “I detest the formulation ‘a film by,’” he once said.1 Elsewhere, he reflected: “I think that there is no auteur in films and that a film is something that pre-exists in its own right […] you are trying to reach it, to discover it.”2

L’amour fou is a humane and reflexive portrait of a director—two directors—at work, but it is also an audacious critique of Rivette’s mileu’s obsession with individual mastery. Desperate to elevate the classicism of Racine’s play into something immediate and raw, Sébastien compulsively workshops his actors’ entrances, manoeuvring their bodies like chess pieces. He has also cast himself as the play’s most powerful force, King Pyrrhus—a way, observes Labarthe, of directing it from within. Yet, on the edges of the amphitheatre, Sébastien’s vulnerability is a palpable storm—he fidgets and paces; he wriggles his way into the transitory comforts of other women’s bedrooms. Meanwhile, with gauche intrusions into the troupe’s psyches (particularly that of Marta, who he questions in the cloakroom with the self-described tenor of a “psychoanalyst”), Labarthe flails to shape the theatrical process into a linear one. What emerges is far more uncertain; the film begins and ends with the same, futile tableau: a restless audience, waiting for the show to start.

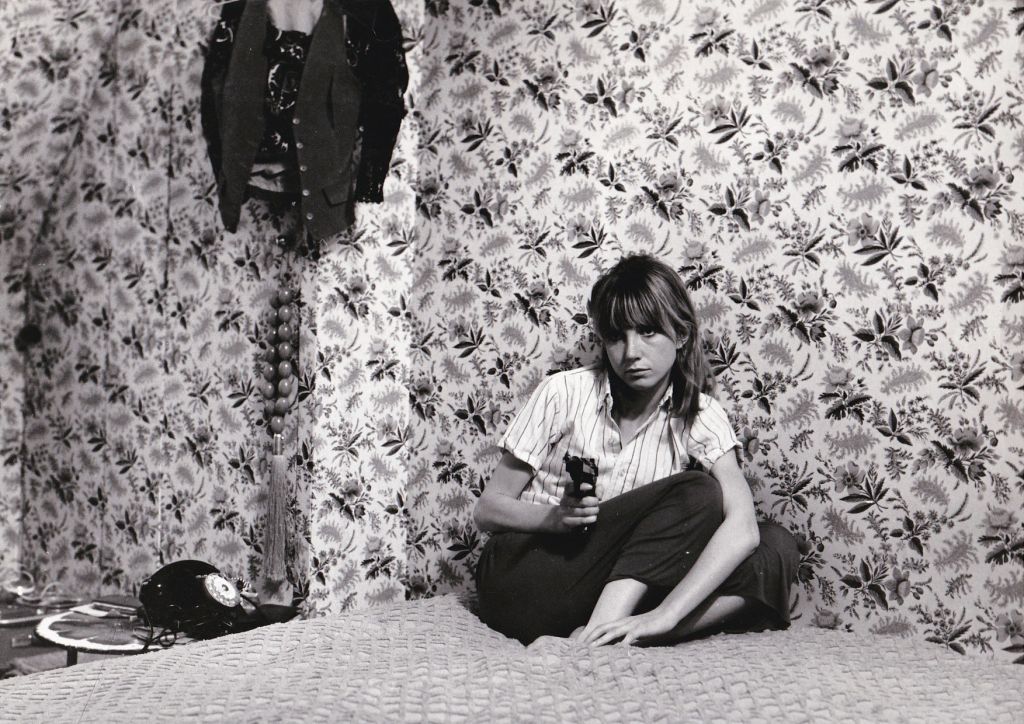

While Sébastien rehearses, Claire, alone in their apartment, enacts her own, innovative recitations. She transmutes her fears about their marriage into rhythmic, self-taped monologues. She narrates glimpses of life from her balcony window (“Two nuns pass. One spits, the other wipes her nose”), searches Paris for a dog whose eyes resemble her own, and unpacks a Russian doll the size of an infant, moving faster and faster until her bed is engulfed by its duplicates. The creative impulse, the film suggests, is indistinguishable from the desire to refract oneself in the world—to find oneself in others, to dig for a sense of unity at the base of solitude.

The film’s genesis began with Rivette’s poaching of Ogier and Kalfon, around whom he sketched L’amour fou after witnessing their elastic, eruptive performances in Les Bargasses—a work of avant-garde theatre directed by Marc’O (who in 1968 would also conduct the two actors, along with Pierre Clémenti, as the rebellious celebrity gang of Les Idoles). In a sharp turn from the classical, noir-ish plotting of Rivette’s debut feature, or of his Anna Karina-starring period piece cautiously adapted from Diderot, L’amour fou welcomed a degree of improvisational freedom that shocked even its stars. When, at the peak of their characters’ manic revelry, they started to graffiti and lacerate the set, Rivette didn’t intervene.

Despite its duration, L’amour fou feels more like a high-wire act than a slow burn, maintaining a constant, teetering quality between its states of agony and impassioned joie de vivre. Kalfon, with his sprawling stature and dark eyes, transmits both the authoritative posturing of a director and the frenzied bewilderment of an outgrown child. Ogier—who Marguerite Duras famously admired as the embodiment of “absolute vagueness”—conveys a transcendent vacancy. Her soft flux in expression evokes an ambient, clawing discontent, and she is prone to slinking from sweetness into sudden cruelty. When troupe member Puck (Liliane Bordoni) detects Claire’s loneliness, she gives the couple a kitten, which Claire takes to hissing at and refuses to name. “By the way, the kitten’s dead,” she lies to Puck over the phone, laughing without a beat. “I’m kidding,” she relents, then doubles back: “He’s just very sick.”

A fascination with magic would later come to the fore of Rivette’s body of work, alive with pirates, magicians, and phantoms, such as the goddesses of Duelle (1976)—a queer fairy tale in which Ogier represents the sun, enwrapped by a gold foil trench coat. Though a seemingly minimal and realist film, with its lifelike performances and a visual language that rhymes with Chantal Akerman’s structuralist renderings of domestic space, L’amour fou is itself quilted with a sense of mystery, since reinforced by its original print’s mythic destruction. Its cuts often feel premature, tearing into scenes or suturing moments of rage and adoration, violence and embrace, with little batting to soften the blow. Elsewhere, intimate realms are possessed by distant forces. Near the film’s end, Sébastien wags rehearsal so that he and Claire can spend time together, playing until they are crumpled on the floor, too exhausted to go on. Before this, as they rock one another, they start to speak in desperate, nonsensical tongues. But the language of lovers, however ridiculous, is a private one, and their voices are soon muffled by the sound of an unknown ocean.

* * * *

The Melbourne Cinémathèque has programmed L’amour fou alongside Les photos d’Alix. The pairing concludes a complete Eustache retrospective, which included a screening of his infamous The Mother and the Whore (1973)—another recent rediscovery which, echoing L’amour fou, casts a piercing light on erratic yearning and uncertain youth amidst the murky fugue of post-1968 Paris.

In Les photos d’Alix, Eustache’s son, Boris, interviews the photographer Alix Cléo Roubaud. She flicks through a folio of images (still lifes, self-portraits, ghostly renderings of her friends, father, lovers, and stalker), which have often somehow been marred by light tricks or processes of erasure, leaving oblique compositions. At first, her descriptions match up, but slowly they become out of sync with what we are seeing; when she gestures to a human body, there is only a pillow. A picture is not reality, she tells us; it is at once “much less than reality, and much further.” Like Rivette’s, Eustache and Cléo Roubaud’s obstructions playfully undermine the idea of cinema as a tool of explanation and exposure. Images, especially moving ones, bear an inherent futility, but this capacity for disappearance is the crux of their magic. Filmmaking, Rivette says, is “a collective work, but one wherein there’s a secret, too.”3 The labour of the artist is, in part, to safeguard this secret.

**********

The Melbourne Cinémathèque screens films on Wednesdays at ACMI in Federation Square. Screenings are presented in partnership with ACMI, and supported by VicScreen. Full program and membership options—including discounted membership options for students—are available at acmi.net.au/cteq.

Support the Cinémathèque’s 2025 Screening Program by making a tax deductible donation through the Australian Cultural Fund.

**********

Indigo Bailey is a Tasmanian writer and editor living in Naarm/Melbourne. In 2023, she received the Island Nonfiction Prize for an essay about rain sound. She has written for Island Magazine, The Guardian, Voiceworks, and Kill Your Darlings, among other publications.