This weekend, from July 19th to the 21st, the inaugural Africa Film Fest Australia is taking place on Dharug land in Western Sydney. Providing a rich and varied insight into contemporary African and diasporic cinema, the impressive selection of programmed films also includes the first features of several rising directors.

Across the four films reviewed below, forms of distance, whether emotional, physical, or temporal, are employed and played with in fascinating ways. These works—All the Colours of the World are Between Black and White (2023), (Baada Ya Masika) After the Long Rains (2024), Colette and Justin (2022), and Girl (2023)—are all small, tender stories, albeit with vastly different styles and approaches. From an intimate exploration of familial lineage to a brooding tale of inexpressible desire, these films consider how one’s history and community contribute to inscribing their place in the world.

The features program is rounded out by Banel and Adama (2023), which took home the Melbourne International Film Festival Bright Horizons Award last year, Rise: The Siya Kolisi Story (2023), and The Last Queen (2022). The festival will also include two short film screening events and an animation workshop led by animators from Nigeria and Jamaica, Edi Udo and Rubeena King.

* * * *

All the Colours of the World are Between Black and White

In modern day Lagos, the life of delivery driver Bambino (Tope Tedela) is largely confined to his home and modest routine. Seemingly the most well-off in his apartment complex, his neighbours appear to him in fragments; half obscured by a door while asking for money, or at times entirely unseen, like a tormented couple whose loud fights bleed through the walls. The only exception is Ifeyinwa (Martha Ehinome Orhiere), a young woman drawn to Bambino despite an impending arranged marriage.

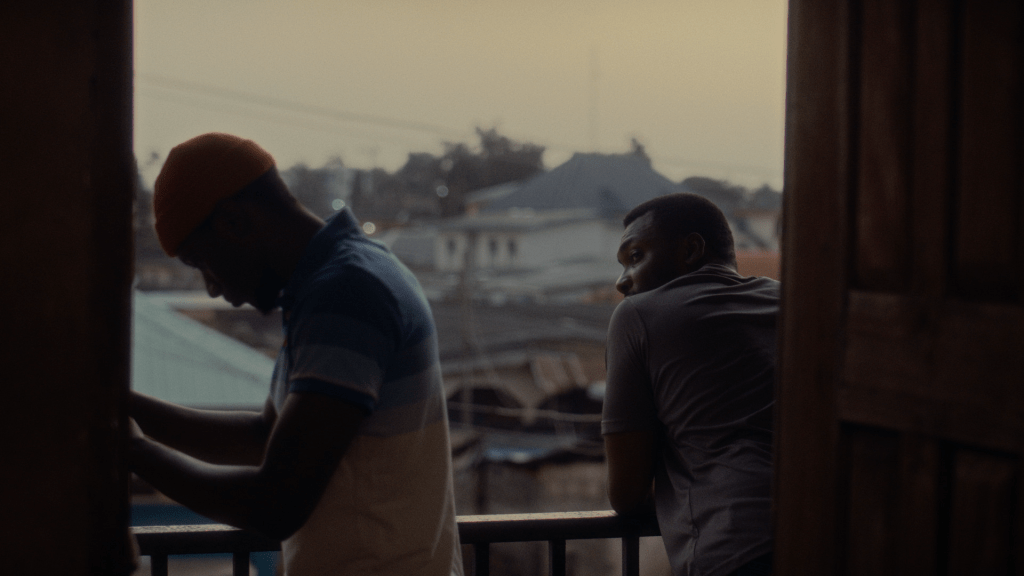

In this romantic feature by Nigerian director Babatunde Apalowo, which earned the Teddy Award at Berlinale 2023, Bambino soon encounters Bawa (Riyo David), a local photographer who runs a betting shop. Taking advantage of Bambino’s knowledge of Lagos, Bawa invites him on various expeditions to capture the city for a photography competition, which—barring a boldly intimate conclusion—lend the film some of its most tender moments. Backdropped by Nigeria’s harsh anti-gay laws, Colours’ plot is otherwise slight: like shifting tides, the film sees Bambino and Bawa slowly moving towards and pulling away from each other, with the primary narrative charge being the largely unspoken yet ever-present threat of violence underlining their growing desire. Cinematographer David Wyte frames Lagos in striking wide shots, while, within his home, Bambino is often sequestered and segmented by creative blocking choices.

The performances here are necessarily reserved—David exudes charm and gentle longing, while Tedela is repressed and simmering. As the occasion of the men’s first meeting, photography becomes a liberating technology for Bambino and Bawa: not merely a metaphor for seeing one another, but an arena where freedom of expression can lend itself to worldmaking. If the men are able to capture the world, perhaps they can also reimagine it for themselves.

* * * *

(Baada Ya Masika) After the Long Rains

In schools, many children are asked the same, relentless question: “What do you want to be when you grow up?” Directed by 22-year-old Swiss-Kenyan Damien Hauser, After the Long Rains tells the story of a young Kenyan girl, Aisha (Eletricer Kache Hamisi), who responds to this question simply and firmly: she longs to be an actress somewhere in Europe. But to get there, she must sail a boat, and to do so, she must first learn to sail. So, she engages the help of a local fisherman, Hassan (Bosco Baraka Karisa), an alcoholic with his own demons.

While the characterisation of Hassan is relatively simple, he and Aisha’s growing bond is sweet to observe, framed by the stunning coasts of Watamu and Lamu Island. Inspired by the bright whimsy of Studio Ghibli films, Hauser strikes a comfortable balance between the wide-eyed immediacy of youth and the broader concept of inherited futures. With a convincingly fraught mother-daughter relationship, Aisha’s commitment to fishing—complemented by her brother’s passion for textiles—prods the gendered expectations that limit young people’s emerging, fluctuating identities. Featuring narration from a grown Aisha, who returns home years later to share her story with another eager child, Hauser allows her memories to shift at times into others’ perspectives, with the humour of her past naivety enriched by these later reflections.

Throughout, there is a compelling thread connecting this cluster of people: characters frequently find themselves out of time, seemingly either too modern or too traditional, perhaps mired in grief or looking too far, impatiently, toward the future. Around Aisha, Hauser also summons a strong, engaging sense of Watamu’s community dynamics, from her school peers to the neighbourhood adults who look out for and guide her. This is a visually vibrant, playful film, with welcome touches of magical realism. Not every creative gambit pays off, but it’s nevertheless exciting to watch Hauser’s abundant creative energy at work.

* * * *

In this essayistic documentary, Congolese French director Alain Kassanda uses probing poetic voiceover, archival imagery, and intimate interviews to piece together the narrative of his family, refracted through the political history of the Democratic Republic of Congo. At times recalling the ethical queries of Trinh T. Min-ha’s Reassemblage (1982), Colette and Justin explores the fragmenting of one’s memories and identity as an ongoing consequence of colonial occupation. Early in the film, after a montage marries footage of colonial-era monuments with dehumanising imagery from Belgium’s archives, the director poses a crucial, irresolvable question: how does one talk about and denounce past violences without reactivating them? “Dominating is photographing,” Kassanda reflects: “Imposing a gaze that confiscates someone’s image, prevents their own narrative.”

At his grandparents’ home, Kassanda unfurls a large map of 1950s Congo before his grandfather, Joseph; later, he observes his grandmother, Colette, working busily in the kitchen. Yet Kassanda rarely, if ever, summons personal nostalgia or sentiment as a crutch. The truth comes broken and difficult through conversations with his grandparents which, in the film’s more gut-wrenching sequences, devolve into ideological disagreement. Sometimes beautifully abstract, other times dense with historical background, Kassanda’s voiceover attempts to make sense of his own identity by way of his grandparents’ experience of the 1960s Congo Crisis and struggle for independence—a history marred, irrevocably, by Belgian colonisers.

* * * *

Girl, the feature debut from British director and playwright Adura Onashile, begins in mystery: we observe Grace (Déborah Lukumuena) compulsively counting her steps to and from the public housing apartment in which she raises Alma (Le’Shantey Bonsu), the eleven-year-old daughter she had at fourteen. With time, details emerge: Grace works evenings as a cleaner, keeping Alma at home semi-permanently while she anxiously provides for their family.

The two have a tender yet troubled relationship; together, they repeat a fairytale-like fable in which Alma’s birth was the product of Grace’s lonely wish for friendship, and they imagine the features of an imaginary home that they’ll one day inhabit. Yet the young mother’s need to protect her daughter also frequently flips into paranoid obstruction. On the brink of tweenhood, Alma spends her lonely nights with a pair of binoculars on the balcony, silently observing and yearning for the neighbourhood from which she’s been distanced.

As the film progresses, its movement across place and time is muddied, somewhat, by a screenplay hesitant to reveal too much (and over-relying, in places, on its stellar soundtrack to guide emotion). Yet its silences and sparing flashbacks, which nestle within and speak through the physicalities of Girl’s formidable performers, do well to evoke Onashile’s thematic concerns without offering simple, digestible answers. When your ability to trust in others has been taken from you, how do you avoid spoiling your child’s own trusting openness to the world? Guided by a fractured narrative, Girl is relatively small in scope but finds, through its characters’ complicated dynamic, a great deal of compassion for those wrestling with the aftershocks of abuse, culminating in an affirming embrace of community.

The Africa Film Fest runs from July 19th to the 21st at Riverside Theatres in Parramatta, Western Sydney. The full program can be viewed here.

**********

Tiia Kelly is a film and culture critic, essayist, and the Commissioning Editor for Rough Cut. She is based in Naarm/Melbourne.