For the sophomore entry of our new column, ‘Beyond the Frame,’ we dive into the glistening detritus of independent, cult, and microbudget cinema with two devoted disciples: filmmaker and Trash Night programmer Kai Perrignon and Felix Hubble, co-founder of DIY film collective and distributor Static Vision. In this conversation, we hear from Kai and Felix about the genesis of their ‘Trash’ proclivities, programming against the grain of institutions and industries, and building community with independent filmmakers—who, they’ve discovered, are often just an email away.

Kai and Felix also tell us about two exciting screening events—Trash Day (a five-film psychotronic marathon, to be held on Saturday the 20th of July) and Neo-Intimacies (a survey of transgression and innovation by way of four recent North American films, on August 3rd)—upcoming at Static Vision’s new home at 47 Melville Road in Melbourne’s Brunswick West.

Rough Cut: How would you define ‘Trash’ cinema to the uninitiated? Can each of you speak a little about how your passion for microbudget and underground film developed, and about any early touchstones that come to mind?

Kai Perrignon: Trash cinema is a catch-all for the disreputable, the forgotten, the disrespected, movies from the fringes. It can encompass everything from a sleazy exploitation picture to a no-budget art provocation. It’s relative; trash is what we throw away, and I want to pick it back up and treat it with the same curiosity and respect provided to more canonised, glossier, and/or institutionally approved work. That’s what I mean when I call Trash Night “a place where the gutter meets the sky.” I’m especially interested in showcasing independent cinema—worthy personal visions that rarely if ever screen and will really benefit from the charged communal screening experience—but Trash can be inclusive of many different textures.

My passion for the microbudget and the underground rose from two places. First, an interest in genre cinema that evolved into an interest in exploitation cinema that evolved into an interest in outsider cinema generally. I remember the first time I watched The Last House on Dead End Street (1977), an infamous, absolutely horrific, and genuine horror masterpiece that cost less than $3000 to make. I had never seen anything so cheap, so alive with the freedom of its modest resources. It seriously scared me, and that excited me. After that, I started looking under more rocks for treasure of all kinds. Film history is littered with the best movies of all time that have been largely ignored by traditional film culture, curation, and academia because of their transgressive subject matter, the class and identity of their creators, their lack of polish, and their accidental or intentional refutation of expected cinematic form.

Second is my own practice as an independent filmmaker. I love the movies, but I can’t see a fulfilling future for myself working in mainstream media. The film and TV industry is entirely funded and mostly led by the wealthy, whose tastes, desires, and hopes for the future of the medium only sometimes align with those of middle and working class artists. Not to say that the big media machine has not produced lots of wonderful art, but it’s a narrow mandate with limited space for diversity of all kinds. I mourn for the millions of talented people who never make a movie or write a book or record an album because they can’t risk the investment or don’t have the time after working to pay their rent, so it is absolutely worth searching for and celebrating those who power through the struggle because they need to express themselves and they want to connect with others on a similar wavelength.

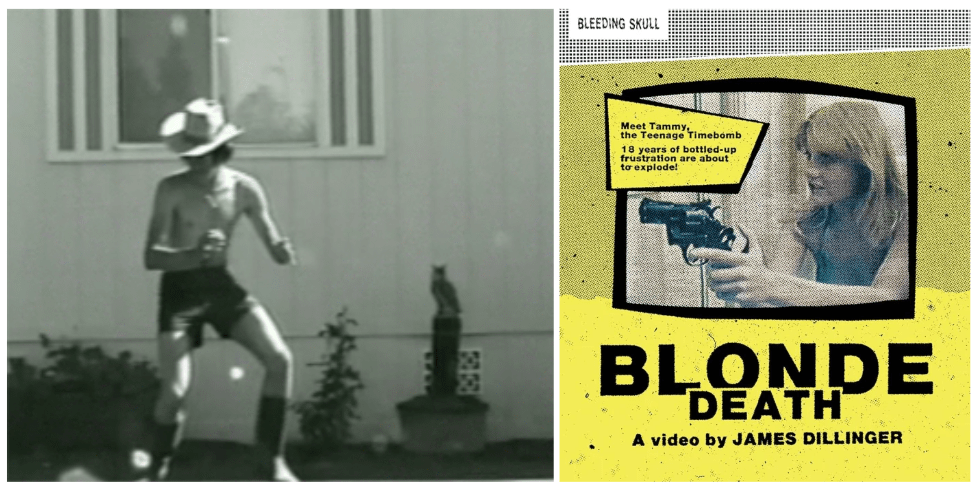

Some key early touchstones for me outside of Last House on Dead End Street include Seeds (1968), LA Plays Itself (1972), The Iron Rose (1973), Je Tu Il Elle (1974), Personal Problems (1980), Possibly in Michigan (1983), Blonde Death (1984), Tales from the Quadead Zone (1987), Alien Beasts (1991), Touch Me in the Morning (1999), After Last Season (2009), Flooding with Love for the Kid (2010), Local Legends (2013), and Difficulty Breathing (2017)—all independent movies that expanded my conception of narrative cinema.

Felix Hubble: I basically agree with everything Kai has said. However, my microbudget canon veers more towards American pre and post-mumblecore/gore cinema. This includes films like Assholes (2017), Dead Hands Dig Deep (2016), OK, Good (2012), Viva (2007), Terminal USA (1993), Mondo Trasho (1969), A Horrible Way To Die (2010), Empire Builder (2012), I Hate Myself 🙂 (2013), Mary Jane’s Not A Virgin Anymore (1996), 0s & 1s (2011), The Dirties (2013), Jobe’z World (2018), and Stinking Heaven (2015).

I think a lot of that comes out in the sort of programming Static Vision does, but it’s always a joy to see how my reference points will clash with those of Kai or other collaborators I’ve worked with like Conor Bateman and Eleanor Smith in Static Vision days’ past, or Ing Dieckmann and Joseph [Pallas] at Pink Flamingo Cinema in Sydney. It’s really fertile ground for constructing programs I’ve found personally very creatively fulfilling, and hopefully those collaborations have been engaging to our audience throughout the years. We’re constantly talking about this stuff and brainstorming new programs, and it’s so much fun to see everyone’s different viewing habits and creative backgrounds clash.

RC: How does this love for underground cinema influence your approach to running a DIY screening space? I’m thinking, for instance, about how affordable your ticket prices are. Can you talk a bit about your ethos at Static Vision HQ—but also some of the practicalities behind implementing it?

KP: At the end of the day, everyone working at the space has a day job or jobs, especially Felix. So there’s always lots to do, never enough time to do all of it. But the DIY nature of the project allows for and even encourages some rough edges. We’re building up and improving the space every week, aiming to soon have a cosy regular screening space, but if it gets too fancy and put-together it loses the good atmosphere.

As a screening collective, Static Vision is not wholly or even mostly focused on underground cinema, though that’s certainly the main flavour of its next couple of events and my Trash Night banner. The end goal of any given program is for people to show up and have a memorable, engaging time at the cinema; even the most obscure screening is intended to be as appealing as possible. Still, you have to throw some bones to audiences who are understandably wary of spending their money on something less than predictable.

One of those bones is the ticket prices. We want people to embrace the space as a welcoming, affordable, community zone where they feel comfortable taking chances on cool screenings and want to hang out generally—but also there are rights to secure, rent to pay, maintenance to be done. It’s a balance. My instinct is for everything to be free, but that’s why I’m not in charge.

Another bone is building trust with the audience. Static Vision has developed a strong reputation for entertaining, boundary-pushing programming that speaks well to the current moment, regardless of budget and genre. I’m thinking of the recent Obsessions festival, which featured packed screenings of both big retro hits like Gregg Araki’s Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy and Masao Adachi’s underground political provocation Revolution +1 (2023). So hopefully that reputation in tandem with consistently strong, specific programming continues to help people take chances on movies they wouldn’t see elsewhere.

FH: It’s always tricky to strike a balance between keeping the lights on and keeping the space and our festivals accessible, but generally, I think it’s extremely important to keep the prices down and the vibes approachable to keep cinema alive. Many of the major cinemas are killing off their audiences by making their offerings too unaffordable and, frankly, often extremely boring. The cinema space should be so much more than just a delivery mechanism for sub-standard studio slop, with massive marketing budgets to convince audiences the material is somehow more worthy, relevant, or culturally important than all the great independent, lo-fi, weird, challenging, and forward-thinking work being made worldwide that generally doesn’t make it into most cinemas or find its way onto major streaming services.

We all have a very punk/DIY ethos around this, and there are obvious trade-offs—our work/life balance is generally pretty shot to keep this all going, for example—but I think it’s super important for these films to be presented in a space like Static Vision HQ, where we prioritise showing movies you generally can’t see in screening spaces elsewhere, or at least presenting them in a unique context with thoughtful programming, to an adventurous and open audience. It’s a lot of fun when it hits, and still pretty great when it doesn’t.

My vision for the HQ (no pun intended) is a zone in which we can screen anything we feel is interesting or has some merit on our own terms, without the shackles of managing the expectations and restrictions of external venue partners. We’re keen to open the opportunity to screen interesting stuff up to as many people as possible further down the line, training our next generation of curators, programmers, and general cinema weirdos who go down the path of putting on events for their friends and the community.

RC: I can imagine that screening elusive and obscure films could raise particular challenges for you as programmers, but perhaps also certain freedoms, in the sense of these films existing outside of a mainstream commercial sphere. Can you speak to the process of sourcing films and building relationships with underground filmmakers?

KP: In terms of sourcing films and developing relationships with filmmakers, a lot of it is just directly reaching out to people online. In my experience, people are excited to talk about their art and very willing to give some of their time to enthusiastic programmers. Especially if the work hasn’t received the love and attention it deserves. Some of these works may be in a grey area in terms of rights, and all you can do for works of that nature is seek the filmmakers’ blessing.

I’ve had the privilege to talk to a fair few incredible and generous filmmakers through Static Vision over the years, but two people stand out in my memory. The first is feminist video artist Cecelia Condit (director of Possibly in Michigan, Beneath the Skin, I’ve Been Afraid, and many more), who talked extensively to me and Ingo Dieckmann TWICE. In addition to being an artistic hero of mine, she is a truly cool and fascinating person with lots of insight and wild stories over a long career. It was a joy and an honour talking to her, and Ingo and I nearly lost it when she praised us as interviewers.

The second is outsider horror filmmaker Chester Novell Turner (director of Tales from the Quadead Zone and Black Devil Doll from Hell), who I just never in a million years imagined I’d be able to speak to. His films are so specific to the time, place, and headspace of their creators, and no movies since have been able to capture the same funny/uncanny/horny/tragic murderdrone atmosphere. They mean a lot to me. But they’re pretty obscure, and Turner was in his 70s at the time, so I had low hopes of being able to contact him. He seemed more legend than person. Somehow Felix managed to get ahold of Turner’s daughter/manager’s phone number, and I interviewed him over a crackly connection for about 45 minutes. It was surreal. He was a total sweetheart. I hope he finishes the sequels he talked about.

FH: Throughout the years, I’ve found that filmmakers are often the easiest people to engage with in the chain when it comes to screening their films. Thankfully, when it comes to independent and underground cinema, the rights to screening these films often lie with the filmmakers themselves. I would encourage everyone to (occasionally and respectfully) reach out to filmmakers on Instagram or via email (if you can track them down) etc. when you resonate strongly with their work, especially their early films, as you’d be surprised how often such feedback will be warmly received.

We’re in a special zone with the HQ (and back when we were doing online streams), as we’ve been able to put on events whenever we feel like it as opportunities arise, and this process helps us build those relationships. For a lot of filmmakers, their films won’t screen in Australia without independent collectives, film clubs, etc. reaching out and organising an event, and a simple DM often makes this work and can lead to really good stuff beyond just permission to screen something, like information to informal intros or full-blown Q&As. There’s a really big DIY screening scene starting to form across the world right now, and most of this has come about through the internet.

Soon after Trash Day, we’ll be hosting another single-day screening event of new North American cinema that’s wholly come about through the process of DMing filmmakers we’ve befriended over the years (and all the films have some connection to internet-driven relationships/the ways in which the online sphere has altered our interpersonal relationships).

I briefly met Eugene Kotlyarenko in person in 2018, but our relationship was firmly cemented through the internet. He’s been a great supporter of Static Vision and many other screening collectives around the world. We have a shared focus and interest in digital cultures and surveillance, as well as a DIY/community ethos (even when he’s working on larger projects), which has been convenient from a screening perspective as practically all of his work has been applicable to our programs. It’s also meant that we’ve been able to establish the best possible atmosphere and context for the presentation of his work, and to delve deep into discussion with him.

Alongside Eugene, we’ve had the opportunity to collaborate with a few very surprising guests with just a single DM or email, including a two-hour Q&A with Paul Schrader hosted by Keva York and myself (in which he divulged the entire plots of the then-incomplete The Card Counter and Master Gardener), a six-hour showcase of the works of Guy Maddin and the Brothers Johnson (complete with live discussion between each film), and retrospective screenings of Anna Biller’s whole filmography accompanied by two separate two-hour chats. I still pinch myself whenever filmmakers are so cool and generous with their time and films like this, especially given we’re on the other side of the world and these sorts of events don’t have any noticeable impact on their profiles—they’re just true lovers of cinema, DIY cinema in particular.

RC: Felix, what can we expect from Neo-Intimacies?

FH: Neo-Intimacies is a four-film survey of contemporary North American* (including Canadian) cinema, showcasing the most exciting new movies in the region. The films are all bold, brash, bad romances from unique emerging filmmakers with interesting careers to come. These are four of my favourite films of the past couple of years that haven’t fit perfectly into past Static Vision programs for whatever reason, and they work wonderfully together.

With the Philadelphia-set This Closeness (2023), Kit Zauhar is carrying the torch for the mumblecore tradition, updating it within the context of new sensibilities and concerns, and she’s already hard at work on another exciting-sounding feature. The LA-set Dogleg (2023) is a fascinating meta-film nominally about director Al Warren losing his dog but ultimately about the filmmaking process generally and its own creation specifically. The NYC-set The Feeling That The Time For Doing Something Has Passed (2023) is a fucked up, self-deprecating BDSM comedy that expands on the themes and vibes of writer/director/star Joanna Arnow’s radically honest mumblecore-documentary hybrid I Hate Myself 🙂 (easily a top 10 of all time film for me); I can’t wait to see what she does next. Finally, Canadian writer/director/editor Nate Wilson’s The All Golden (2023) is a lo-fi experimental polyamory soap opera that is sure to polarise and pop with an audience, for good reason—it’s true contemporary transgressive art worth fighting for; Kai and myself love it.

**********

Trash Day will be held at Static Vision HQ on Saturday, the 20th of July. You can explore the program and purchase tickets here. Neo-Intimacies will screen on the 3rd of August, with more information coming soon. Follow Static Vision on Instagram, Facebook, or X to stay updated about future events.