“Upon the right to write badly depends the right to write at all,” Lionel Trilling wrote, and though it changes the phrase’s meaning, it may just be as true to say that upon the right to review badly—that is, to write a bad review—depends the right to review at all. What right have I, then, to review Gabriel Carrubba’s Sunflower—the autofictional debut feature of a young Melbourne filmmaker, shot in the suburb, Berwick (not to mention the house), in which he was born and raised, about a gay teenager overcoming bullying and a hate crime to find happiness and self-acceptance? To review such a film badly, whatever its quality, would not only be callous—it would be tantamount to declaring generational war: non-binary Gen Z brat too young to vote during the gay marriage referendum performs hatchet job on the very notion of queer millennial joy. And yet: I saw the film I saw, I felt the way I felt, and I have been asked to put those feelings into words. Just know, reader, that I do so with a respectful amount of shame.

The film follows Leo (Liam Mollica), a high school student in the midst of a sexual awakening, grappling with self-hatred, the scrutiny of his peers, and the ever-present coercive threat of homophobic violence. He hangs out with his best friend, Boof (Luke J. Morgan), a mulleted, insecurely masculine gym rat with whom he shares a palpable but unspoken erotic charge. He flirts with, kisses, and half-heartedly strings along his classmate Monique (Olivia Fildes); bickers with his family; frequents gay chatrooms; and, after a series of events I won’t spoil, forms a stable relationship with his younger brother’s closeted but self-loving friend, Cam (Jacob Pontil-Scala).

The value of autobiographical film is surely meant to lie in its unique insight into its subject matter: its ability to capture a truth of texture and of feeling that can only be drawn from life. Sunflower captures such truth most forcefully in the scenes around Leo’s dinner table—in which his family’s obvious love for one another is constantly waylaid by squabbling—as well as the scenes of messy, fleshy, sublimated, and aborted lust, both gay and straight, around which its first half is organised. The games Boof plays with Leo (wrestling on the grass, having Leo take thirst trap photos of him, engaging in mutual masturbation) are amusing in how effortfully they work to conceal what animates them—Boof’s knowledge of Leo’s desires, and Boof’s own desires, which are even more violently repressed than Leo’s. They are also heartbreaking. Leo’s scenes with Monique, too, are tenderly observed, and visceral in their awkwardness. Yet, elsewhere, the film just isn’t quite artful enough to sustain this feeling of truth—not with exchanges like: “Where do you think it ends?” “Where do I think what ends?”—pregnant pause—“The Universe?” Nor does the casting help. Why, one must ask, is everyone who attends this high school clearly in their mid-twenties? And why are all the boys impossibly cut? By the time Leo—looking twenty-five at least, buff, wearing shorts, a yellow t-shirt, and a backwards cap, carrying a skateboard—is told by his brother, “Hey, Leo. You’re still my brother, man. Nothing changes,” it is unclear whether he has come out as gay, or as an undercover cop.

It’s not just the characters’ ages, either; there is a generally out-of-time quality to the film. In high school, micro-generational differences of one or two years can be seismic. There is no sense of these nuances in the film, however; even accounting for regional variations and personal differences, its characters’ sexual politics and relationships to social media and chatrooms feel like they could be from ten, fifteen years ago. One gets the sense that Carrubba has tried to transplant the story of his own youth, unaltered, into the present day; the result is ever-so-slightly surreal. Elsewhere, the film’s anachronisms are purely odd. The teenagers go to the cinema to see a black-and-white film (it isn’t listed in the credits, but sounds a lot like Night of the Living Dead [1968]). In class, they are shown a black-and-white sex-ed video that sounds even older, which dispenses such crackly-voiced truisms as, “For both boys and girls, hair grows under the arms, in the pubic region, and elsewhere on the body […] These physical changes make the boy feel more manly, and the girl more womanly.” And—in a moment of dramatic irony—“They begin to be interested in members of the other sex.” Alas! If only our protagonist had gotten the memo sooner—before the age of twenty-five, perhaps, or in the year 1940, when the video seems to have been made.

The real issue is not with the filmmaker’s choice of sex-ed material, though; it is that the film itself tends to feel like sex-ed material. There are nods to arthouse aspirations, sure. Synthesisers swell in moments of intense emotion because that is what synthesisers should, we understand, do; the film is shot in an aspect ratio just a little wider than 4:3, because that, we understand, is the aspect ratio in which prestige films should be shot. Until, that is, the frame expands to widescreen in the film’s final act, in a sort of visual coming-out-of-the-closet (get it? like Leo)—a move cribbed, tellingly, from Xavier Dolan’s Mommy (2014), another film about a teen with problematic desires skateboarding around suburban streets, that, for all its flaws, at least had the bravery to be unapologetically off-putting. But these remain stylistic flourishes adorning a film whose basic aim seems, at every moment—even its most genuinely sexy ones—to be educational. “I really wanted to showcase the truth of my experience, which was quite positive, and to show kids that: Hey, there’s someone who’s been through life who understands and can look at you and still love you for who you are,” Carrubba has said; “I hope it encourages parents to stop putting pressure on kids.” These are noble goals; hopefully Sunflower will be successful in achieving them. Yet, in excising all that’s extraneous to them—Leo’s interests, for example, which here seem limited to skateboarding and gay sex (hey, that’s plenty)—Carrubba risks excising precisely the details that distinguish an educational video from art.

But then—why can’t an educational video be a work of art? Is there a law that says so? And if there is such a law, surely it should be the job of queer filmmakers, as much as any, to break it? Of queer aesthetic impulses, camp certainly gets the most airtime, but the queer impulse to educate is just as enduring. I think of Toshio Matsumoto’s Funeral Parade of Roses (1969), a retelling of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex as the story of a trans sex worker, Eddie, interspersed with fourth-wall-breaking interviews in which its cast members speak to camera about gender, sexuality and Tokyo’s underground queer bar scene; Pedro Almodovar’s All About My Mother (1999), in which another trans sex worker, Agrado, recounts the gender affirming surgeries she has undergone—what each cost, what she’s done to get them, and what they mean to her—to entertain a crowded theatre when a play is cancelled; or Donna Deitch’s Desert Hearts (1985), whose characters are constantly monologuing to one another, and whose central action is organised around a very particular education: the education of an older woman, by a younger one, regarding the torments and joys of lesbian desire.

A line in that film, spoken to the younger woman by the older, sums it up well: “When I retire, I will simply write a short story for my revenge.” Besides being perfect, this line demonstrates a truth quite central, I think, to queer art. One makes art to have authority over one’s experience—an authority queers have historically been denied, with overt queerness typically having been relegated to silences, margins, the gaps between words, or, at best, to the punchline of a straight person’s joke. Yet to transform one’s experience into art is, in some irreducible sense, to falsify it. These two impulses, which in many ways seem like opposites—to educate and to falsify—are really twin manifestations of the same desire: the desire to speak.

Yet to transform one’s experience into art is, in some irreducible sense, to falsify it. These two impulses, which in many ways seem like opposites—to educate and to falsify—are really twin manifestations of the same desire: the desire to speak.

—Joel Keith

Many of the best queer films—certainly the three I’ve cited above, albeit to varying degrees—tend, then, to combine these apparently contradictory impulses: taking their opportunity to educate an audience that needs educating, while also revelling in artistry and artifice, fantasy and falsity. Sunflower, however, does only the former, untempered by any sense of irony or humour—any of what Donna Haraway calls “serious play.” Which begs the question: exactly what kind of education does the audience of the Australian film festival circuit, which Sunflower has been touring, need? How vital is it to promote awareness of the concept of gay people, when your and my bank and insurance company, not to mention Victoria Police, all have floats in the Midsumma Pride March?

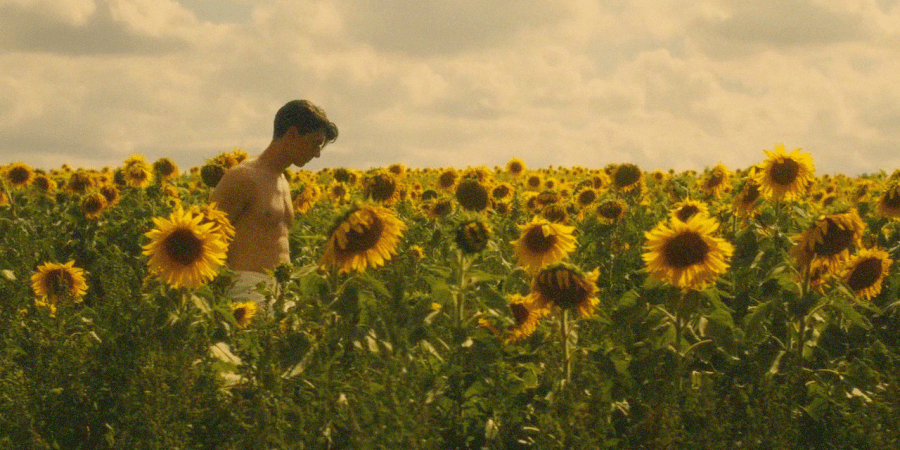

I think of Paul Mescal’s character, Harry, in Andrew Haigh’s All of Us Strangers (2023), reflecting on the mainstream adoption of the word ‘queer’: “Queer does feel polite, somehow…it’s like all the dick sucking’s been taken out.” Leo’s scenes with Boof feel true, and at times even hot, because the desires animating them remain unspoken, sublimated, acted out in absurd masculine charades whose truth lies precisely in their falsity. His relationship with Cam, on the other hand, which is meant to seem freeing, is as frictionless and devoid of eroticism as microfibre on glass. The issue here is not the notion of a happy ending; it is that Carrubba seems to believe that, in order to convince us of Leo’s worthiness, he must remove any of the narrative conditions—passion, ambiguity, risk and, yes, even a sense of threat—that could give rise to a desire the audience might share. Leo must go from gay to queer, so to speak: he must only be seen in dappled sunlight, his sex scenes must cut away before orgasm—in short, the dick sucking must be taken out of him. It’s enough to make one want to re-legalise same-sex marriage.

However flimsy this particular brand of assimilationism is as a political ideal, it is an even flimsier aesthetic one. Carrubba’s loyalty to it is especially frustrating because it is exactly in Sunflower’s observations of the frictions of contradictory desires—frictions which it wants, and eventually manages, to do away with—that the film is at its best. I’m thinking of the scene in Monique’s bedroom in which she and Leo almost have sex. She takes off her shirt, then orders him to undress; not unkindly, but with a force she does not know she wields—or perhaps suspects she does, and wants to test. He strips. She kisses him, but he fails to get hard, so she goes down on him. Still, he can’t get in the mood. She asks if he’d like her to stop; defensively, he tells her no. Then, looking at a picture Monique has painted of sunflowers in various stages of bloom, something in him stirs. Grimacing, he comes abruptly in her mouth. Monique is annoyed; Leo starts dressing, quickly, apologising, claiming there’s something wrong with him. Eventually, she comes out with it: “Are you gay?” “No,” Leo says. “Because if you are, it’s—” “I’m not gay, don’t touch me, I’m not fucking gay,” and he leaves the room. Alone, he roams for hours around Berwick’s empty streets—coming to sit, just as dawn begins to touch the sky, across from a lit-up ferris wheel. As he stares up, the ferris wheel’s lights throw each of the colours of the rainbow flag, in sequence, across his face. It brings him little comfort.

Sunflower is now showing in Australian cinemas.

**********

Joel Keith is a writer and musician living on unceded Wurundjeri land. Their work has appeared in Overland, Island, Cordite, The Suburban Review, The Big Issue, and elsewhere. They are an editor at Voiceworks. You can find them on Instagram @keithyjoel, or anywhere else, happier.