“I mean, we’re in a fucking cinema.” Philip Brophy looks around at the Art Deco interior lounge of the Ritz Randwick, where a 2K restoration of his cult 1993 film Body Melt has just been shown as part of Cinema Reborn’s 2024 program. Surrounded by fake plants and boutique furniture, he groans: “I feel like I’m in Beverly Hills.” We’re discussing the outer suburbs of North Melbourne, where he grew up, and the impetus for staging his story on a no-through road in a fictional city called Homesville. “I hate the fucking inner city,” he continues. “Things are more interesting outside of it.”

“What we’ve got in Body Melt, the houses that don’t have any old-world charm? Yeah, they’re just new, and kind of cheap, and, you know, pretty ugly. That’s what they are. And that’s what people fucking live in.” Brophy is referring to the ordinary and largely identical suburban homes in a newly-built housing estate called Pebbles Court, where much of his film takes place. Pebbles Court reimagines the scenery of the soap operas Australia has become known for internationally since the 1980s as a place of outright terror rather than stifled kitchen table drama. According to Brophy, everybody—even those in so-called “dead-end housing estates”—like the one in Body Melt, needs good neighbours.

In Brophy’s dark suburbia, the cul-de-sac is treated as a technology of the state, designed for community self-supervision. At the end of the street, the houses in Pebbles Court turn inward to face one another, circling around a dead end. In this way, neighbours are invited to assemble—presumably to gossip about one another and chew the fat. The suburban cul-de-sac functions much the same as a panopticon, a rotunda where prisoners are housed in captivity. According to Michel Foucault in Discipline and Punish (1975), the architecture of a circle invokes vigilant self-regulation. To be watched at any time, even by fellow inmates, compels obedience in the contained subject. Even without a prison guard, the panopticon continues to function, surviving on a form of surveillance that is ritually internalised.

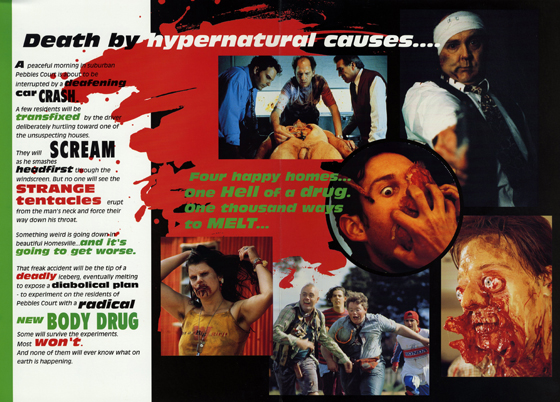

In Body Melt, the residents of Pebbles Court are subject to a nefarious experimental scheme carried out by pharmaceutical company Vimuville. Body Melt leans into the conspiratorial concerns of a medical-industrial complex, creating its very own Big Pharma bad guy. Their vitamins are dispensed from the mailbox to the unassuming locals of Homesville, offering them the chance to administer their own elimination. It’s like the three-panel meme format: They feed us poison / so we take their ‘cures’ / while they suppress our medicine.

Pebbles Court may be a dead end, but death plagues the film’s characters right from the start. In the opening sequence, a “learned chemist” (Robert Simper) who has developed a “moral conscience” is unknowingly poisoned at Vimuville, where he works. After discovering the schemes of his employer, he heads straight for Homesville, presumably to inform the so-called guinea pigs of Pebbles Court. He has just arrived at an Ampol self-service gas station when he begins to feel an internal disturbance. Reaching for his throat, he asks the clerk for detergent. As if to reverse his symptoms, the chemist guzzles the bottle, and after offering to pay, stumbles out of the station to get back behind the wheel. “Fucking pill-poppers,” the clerk yells out while dialing the police to report the drug-induced driving. “Why don’t you just get some fucking sleep!”. Here, Brophy is playing on the prevailing fear of a mounting drug epidemic in the outer suburbs, which has only been exacerbated by a dependence on driving in a place without adequate public transport. “When you grow up in nothing, you learn what nothing is,” the director explains.

The film takes a turn when two unassuming teenage boys from Pebbles Court, Sal (Nicholas Politis) and Gino (Maurie Annese), find themselves “lost in the middle of nowhere” on their way to donate sperm at the pharmaceutical facility. They are quickly greeted by a family with frightful teeth and unwavering smiles, living in rural backwater squalor. The amped-up abjectness of their ‘humble’ existence is designed to provoke disgust, just like the sputtering and spasming bodies that pervade the film. At every stage, Body Melt dares its audience to turn away. What does it mean to live like this and look like that?

“I guess this is that clear country air we always hear about,” one of the boys says to the disfigured patriarch Pud (Vincent Gil), to which he replies “Everything in the country ain’t always that fresh.” Their rural existence is one of neglect; are those jettisoned from society responsible for their own abjection? What responsibility does the state have to its citizens—good, bad, and ugly? In staging these scenes, Brophy parodies and explores the phenomena of blame that plagues our social condition. In Body Melt, Pud and his crew represent a ghettoised community of ‘freakish’ social pariahs, relegated to an unknown territory in “the middle of nowhere.”

“The focus of Body Melt was kind of to mock the idea of the advent of smart drugs, [i.e.] cognition enhancers,” Brophy says of the film. “This is before [the] wellness [industry] and, at the time, it was shifting from 80s body narcissism into the brain being the most beautiful thing. Techno rave music was kind of caught up with that, people were drinking smart drinks like fucking guava juice.” Brophy goes on to explain that, before conceptualising Body Melt, he had been writing about horror movies, pornography, and “bodies as sex machines.” “But what I’m really interested in is the plastic materialisation of something. It’s like, right, what does it actually look like, sound like, feel like? All those things, the evidence, the forensics.”

“Now, I’m talking new drugs here,” the coroner says to the detectives in Body Melt as they surround a dissected human body, “not just 70s designer shit or your 80s ghetto powders; I’m talking fucking 90s man, cognition enhancers! Designed to take your mind into new intra-phenomenological dimensions!”

The forensic reports in Body Melt determine death by “hypernatural causes”: a term mostly undefined by Brophy and his film. Hyper as a prefix suggests an excess of (hyperactive, hyperemotional, hypersexual, et cetera). Where the supernatural refers to the existence of something beyond the natural world (a ghost, for example), ‘hypernature’ imagines an exaggerated nature from within. In this case, literally from within the body. In his career as a sound artist, musician, filmmaker, and film academic, Brophy has created what he calls “Hyper Material For Our Very Brain,” all of which is accessible on his website. The brain is moved to a place of the extreme; it becomes a “very brain.” Hyper material is something extra! An additive!

Body Melt makes several breakthroughs in stressing the horrors of the body. “The great thing about special effects makeup is that it’s kind of returning the acting body into a forensic shell,” Brophy says. He excitedly goes on to describe the acting body as “just a lump, a slug.”

“I’ve always gravitated towards making something that shows a human as a body rather than as a person. I’m always attracted and always have been to moving beyond making such a big fucking deal about how important it is to be human. Because, at the end of the day, the one thing that humans will never be able to stop doing is ‘be human.’ It’s stupid to make a big deal about the human story, to champion humanness.” In Body Melt, humans on-screen are reduced to liquidated bodies, and Brophy is asking his audience not to make a big deal about it. “I don’t read fiction at all,” he declares, “I’m just always feeling like the writer is trying to make a point about something.”

Body Melt showed at this year’s Cinema Reborn festival in Sydney and Melbourne. It is streaming in Australia now on Amazon Prime.

**********

Charles Carrall is a writer and critic from Sydney, Australia. He makes up one half of the podcast Vanity Project.