“I used to be very beautiful,” says a female voice at the start of Lyd. “I used to be very famous.” This is no Norma Desmond, but rather a city—the multicultural metropolis that once connected Palestine to the world. With the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the signing of the Sykes-Picot agreement in 1916—a devastating piece of treachery concocted by a Frenchman and a Brit, who sat down with a map they barely understood to carve up the Levant between colonial powers—Lyd’s long period of glamour and prosperity came to an abrupt end.

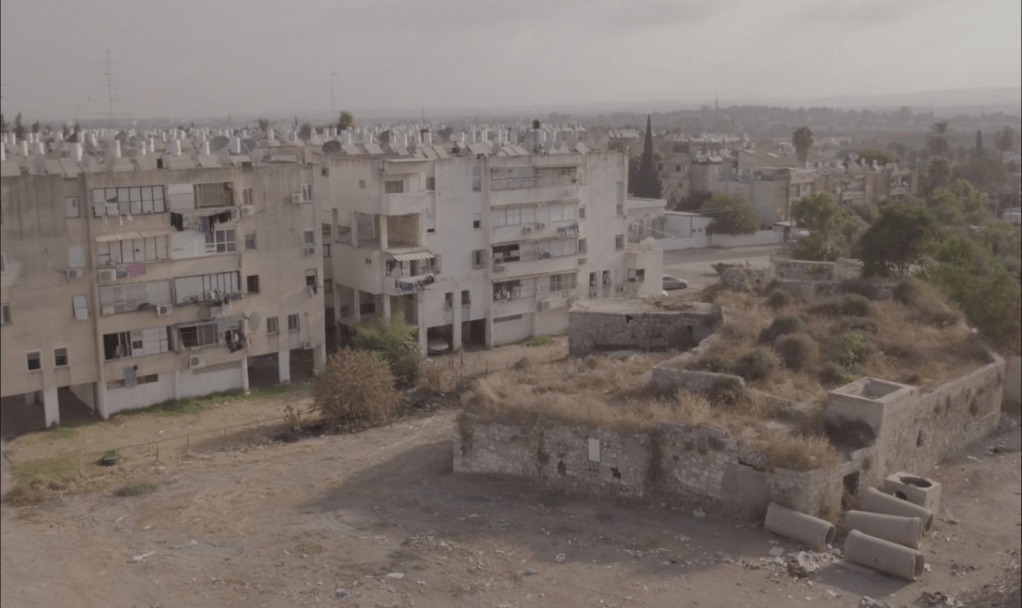

Lyd situates itself a century after the occupation of Palestine by British forces, and over 70 years after the Nakba that saw hundreds of thousands of Palestinians (including Lydians) violently expelled from their homes or else massacred. In this speculative, multi-modal documentary crafted by collaborators Sarah Friedland and Rami Younis, Lyd is not one city, but two. The ramifications of Sykes-Picot were so violent, explains the city-narrator, that they caused a rupture in the fabric of time itself.

In our own timeline, the city falls within occupied Israeli territory, while many of her exiled inhabitants build their lives in refugee camps where they fend off frequent harassment from Israeli soldiers. But in the parallel world envisioned by the filmmakers, no such occupation took place: the Arab nations rejected Sykes-Picot, defeating European colonial powers and—as an independent state operating within ‘The Greater Levant’—ultimately welcoming Jewish refugees escaping the Holocaust, as well as other refugees from across the globe.

Meanwhile, in their alternate reality, rendered in hand-drawn animation, Lyd thrives. Its various peoples—Arab, Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Druze—live freely and equally alongside one another. A statue of Saint George, rendered as “a dark-skinned person from the East, not as a crusading white man,” adorns the town square, and Palestinians of all faiths congregate to celebrate the city and its saint in the annual ‘Eid Lyd’ (a ‘blessed feast’ in Lyd’s honour). But the two realities cannot be so neatly kept apart. A small tear opens up in the pastel skies of the animated city, through which the suffering of real-life Lydians is glimpsed. Over the course of the film, this tear grows wider.

The temporal fracture at the heart of Lyd does not separate two coherent realities so much as it reflects a totalizing condition of striation and fragmentation. Within the ‘real’ timeline, an apartheid regime delineates the Palestinian experience from the Israeli experience: green ID card holders living in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank have one set of rights, while those holding blue ID cards have another. There are diverging narratives for the same events, structured by different programs of language. There are even different names for the city: Lyd was forcibly renamed ‘Lod’ by the Israeli State, but to Palestinians she remains Lyd.

With one of these narrative and linguistic branches backed by ruthless military force, recalling Lyd’s Palestinian origins becomes an act of resistance. As a result, Lydians have had to develop techniques of remembering that are capable of weathering this climate of continuously-attempted systematic erasure. Humour, for example, aids the transmission of cultural memory to future generations, while also housing important stories of struggle and dissent. “How can you tell a person is from Lyd? He’s either bald or has one eye,” says Jehad Baba, a Lydian refugee. One eye because he loves prickly pears, whose sharp thorns are able to gouge out an eyeball, and bald because of the hat he wears, which tears the hair from his head. Baba goes on to tell a story about a one-eyed Lydian who stole a cannon from Israeli forces during the war, aiming to target an Israeli tank, but—due to his skewed vision—hitting the mosque’s minaret instead. In another scene, a grandmother tells of having to hide money from Israeli soldiers “in a weird place,” at which point the kids around her erupt into laughter.

Linear time is an important weapon to genocidal regimes, which attempt to stamp out resistance by invoking a looming and inevitable end that cannot be reversed. With many of the physical Palestinian structures in Lyd now razed to the ground, memory is a form of temporal intervention that is essential to survival. Towards the end of the film, a schoolteacher named Manar El-Memeh puts her job on the line by delivering a workshop to children in which she asks them to explain what being Palestinian means to them. “Where is Palestine?” she asks. To her dismay, they deliver confused answers: “In Gaza,” “Saudi Arabia,” “The West Bank,” “The Emirates.” In “Iraq!”; “Jordan!”; “Syria!” By the end of the class, she’s in tears. “If these stories die,” says El-Memeh, “how do we prove there even was a Nakba?”

Linear time is an important weapon to genocidal regimes, which attempt to stamp out resistance by invoking a looming and inevitable end that cannot be reversed.

—Lauren Collee

As many other peoples know, the only worse evil than living through a genocide is having to prove that a genocide has been—or is in the process of being—attempted. Ultimately, the animated Lydians cannot ignore the cries of their live-action counterparts. Before the credits roll, they creep through the wormhole from their utopia into a living hell. The obligation we bear to one another stretches even across parallel worlds and alternate timelines, which are never as separate as they may seem. Speaking to us from the “wound” between fiction and reality, Lyd asks her audiences to think carefully and expansively about how stories transmit futures. In the city’s own words, “if we don’t imagine a world that can include us too, we want to be able to build the world we want. If we don’t imagine, we will end up in someone else’s world, shaped by their imagination.”

* * * *

Lauren Collee: I want to begin by asking you about the animated parts of the film, which beautifully render a reality that runs parallel to the one we are familiar with. How did you go about working with animators to create the look and feel of this world? Was the use of animation purely a practical choice, or were there other factors in the decision to make the other Lyd an animated one?

Rami Younis: The good thing about animation is that it enables you to create the universe you want, without constraints. For example, we wanted to put two characters from a refugee camp back in their hometown of Lyd, but they are not allowed to get in since they live in the West Bank and the apartheid regime forbids them from entering historical Palestine. But in the animation we could put them where they want. We just needed to record their voices for their avatars, who would be living in Lyd, going to a university there [for example].

Also, it is not real and it’s clear to anyone it is a make-believe world. So animation allows for a better distinction between the two parallel realities. Fortunately for us, we found the coolest animation studio called Samaka, based in Egypt. They got us from the beginning, so there wasn’t too much vision-explaining by the filmmakers (myself and Sarah). We also believe in artistic freedom, so they had their input as well.

LC: In this other version of Lyd—the animated Lyd—the city’s emblem is Saint George, while the dragon he slayed is the colonial project. Freed from this dragon, the city of Lyd becomes a refuge in which the Muslim, Christian, Druze, and Jewish people can live peacefully, side by side. I was struck by how Saint George—who is also the patron saint of England—is here reclaimed as a symbol of Palestinian independence, his victory over the dragon standing in for the rejection of the Sykes-Picot agreement and the overthrowing of British colonial rule. Can you speak a bit about how Saint George came to be such an important motif in the film?

Sarah Friedland: One of the things that struck me when I first visited Lyd was the iconography of Saint George everywhere—on doors, posters, cups, etc. This is because Saint George, who is called al-Khader in Arabic, is the patron saint of Lyd and it is believed that his mother was a Lydawi and his body is actually buried in the basement of the Orthodox Church in Lyd. It’s interesting that he is also the patron saint of England. I did not know that, but it makes perfect sense—another example of how ‘the West’ appropriates history to serve its own narrative. Most of the images that are made of Saint George depict him as a European crusader in shining armour, but if his mother was from Lyd, he would actually look much different and should be imaged accordingly.

Eissa Fanous, one of the documentary characters in our film, survived the Nakba and is traumatised by his memories of that time. To deal with this trauma, he turned to art—creating drawings, paintings, and sculptures of Christian Palestinian life in Lyd, including Saint George. And in all of his depictions of Saint George, the saint actually looks like him—he makes himself Saint George, which we loved. In the animated reality, we took this reclamation one step further and we decided to make him [Fanous] a famous artist commissioned by the municipality to create the anniversary sculpture of al-Khader slaying the dragon as an Arabic person, not a European person.

As you noted, the slaying of the dragon in our imaginary commemorates our fictional ‘Great Anti-Colonial War,’ when the European colonial powers were defeated: a celebration of Palestine’s freedom and democratic pluralism. This religiously pluralistic depiction is inspired by historian Salim Tamari’s descriptions of pre-mandate Jerusalem in his book The Mountain Against the Sea (2008), where the city was organised by “mahallat” [a “neighbourhood network of social demarcations within which a substantial amount of communal solidarity is exhibited”], instead of the religiously divided quarter system instituted by the British. Tamari paints a picture of communitarian identity where Muslims, Jews, and Christians lived in integrated neighbourhoods and shared in one another’s holidays. “This sharing,” he writes, “occurred both at the level of popular involvement in the activities of the Other, as well as in the presence of deities and saints such as Saint George (al-Khader) and Saint Elijah (Nabi Elias) whose veneration was common in all three communities.” So, it is the reality of the past that informed our vision of this alternate reality, which means that it is a possible future.

LC: In your film, the city narrates her own story, and in doing so becomes a witness to her own suffering. There’s a particularly moving moment where she describes feeling crushed by the burden of the hopes and dreams of Lydians who have been expelled. While there’s a cinematic lineage of place acting as ‘protagonist,’ it’s usually a much more subtle emphasis. One of the many things I loved about Lyd was how successfully the city transcends ‘setting’ and becomes ‘character’—the film truly does take place within ‘her’ consciousness. Can you talk about what it means to view the story of Lyd from the city’s perspective as opposed to the perspective of those who live there? What were your hopes for what this might bring into the foreground?

RY: That’s a great question. We believe cities have souls, or characters. Think about it: why do we all prefer certain cities over others? The storytelling in this movie is very complex, and we needed to simplify things by choosing an easy-to-follow narrative spine. That said, we didn’t want to do a simple voiceover because it would’ve been the easy and obvious choice. While formulating the structure of the film, Sarah and I kept exploring the many stories of the city and realised how many Palestinian refugees talk about Lyd with awe and pain. It became clear that if the city was a person, she’d be this old, has-been diva, this gigantic star whose glory days are behind her. Even Palestinians who are not from Lyd know very little about its painful history. Then we figured that should be our narrative spine and that we should let this diva tell her story, and allow her to take us back to her glory days. Judging by reactions from Lydian refugees who watched the film, it resonated with them.

LC: Your film contains some revelatory archival interviews with members of the Palmach, a few of whom express confusion and even remorse about their involvement with the Lydda massacre. You can see these ex-soldiers struggling in real time to reconcile their memories of the event with an official narrative. Was this footage difficult to get hold of?

SF: I had read about this footage in an article and we decided we needed to go to the Palmach Archive and see what was there. It was very intense to visit this military archive, and personally scary for me, but at the end of the day, my name is Sarah Friedland (very Jewish) and Rami speaks Hebrew fluently, so when we told them that we were making a film about what happened in Lyd during 1948, we think they just assumed it would be from a perspective that they agreed with and we did not tell them otherwise. Maybe they did not even care. It is impossible to say.

We got a release from the archive to use the footage and did not have to pay for it. The footage was originally shot for Israeli TV and is part of a larger archive of all of the Palmach attacks during the Nakba. Much of the footage we used are the outtakes cut from a TV documentary made in the late 1980s. Even though some of the soldiers in the footage seem conflicted, mainstream Israelis and Jews in the diaspora are proud of this history, so it’s not surprising that it exists or that they gave it to us.

However, I think it is important to think about the role of archives in the Israeli occupation, and how our usage of this challenges that legacy. Since 1948, Israel has stolen Palestinian archival material, including family photographs and documents that affirm Palestinian cultural identity. Much of this looted archive is locked away in Israel’s Military Archives. Some archives, like the ones seized by Israel from Palestinian Research Center offices in Beirut in the early 1980s—mostly records of Palestinian families and villages in pre-1948 Palestine—were considered so important by the PLO [Palestine Liberation Organization] that they were even part of prisoner exchanges. The Palestinian archive is literally treated like a political prisoner—that’s how threatening evidence of Palestine’s existence is to the State of Israel. Israel’s Military Archives, like the Palmach archive, are not accessible to most Palestinians, who are not only barred from accessing the looted photographic and material evidence of their existence, but also from seeing the evidence of Israel’s war crimes that are housed in these archives, like the footage we acquired. So when we went to the Palmach Archive and acquired the footage of the Palmach soldiers in Lyd, we effectively made this footage public and accessible to all Palestinians through our film.

The Palestinian archive is literally treated like a political prisoner—that’s how threatening evidence of Palestine’s existence is to the State of Israel.

—Sarah Friedland

LC: The film ends by reiterating the importance of not only memory for survival, but also of speculative storytelling. How are memory and speculation entwined in the film? Is the film drawing on Afrofuturist practices, or other lineages of thinking against colonial temporality?

SF: We are both sci-fi fans and thought a lot about its long history as a tool for liberation and envisioning new political horizons, like Afrofuturism. I read a lot of sci-fi and speculative fiction—Ursula K. Le Guin’s idea of “ambiguous utopias” informed the alternate reality a lot because we didn’t want to build a perfect world that felt essentialist; we wanted to hint at struggles that would still persist without the occupation. China Miéville’s book The City & the City also helped me to understand a feeling that I have both in Palestine/Israel and the United States, that there are different overlapping cities based on the rights of movement taken and given by the State to different groups of people. This leads to our biggest influence of all, which is reality.

As an American Jew, I was taught an alternate reality about the founding of the State of Israel that is part of the larger worldbuilding project that created and sustains the State of Israel. This alternate history erases Palestine and Palestinians, changes the topography of the land, resurrected a whole language and a nomenclature. There is so much in nation-building that is sci-fi. What we did was use these same tools to make something else, to imagine a more pluralistic world that is closer to the actual history in the region as it existed before the British occupation of Palestine in 1918 and before the State of Israel was founded in 1948.

LC: The project of imagining other possible worlds couldn’t feel more urgent than it does right now. What does it mean to release this film during what is widely felt to be a second Nakba for the Palestinian people?

RY: The idea of telling a story of atrocities and then creating a world where said atrocities never happened proved to be important and it met a need—the need for imagining a different and better reality. During our world premiere, there were Lydians in the audience. We saw the profound impact the alternate reality had on them. For the first time ever, they got to see a version of this dream they’ve been hearing about since childhood—the promised land of Lyd in Palestine. The occupation can take many things from us. But what’s the one thing they can never take? Our ability to imagine. And what’s the first step towards creating a better reality? Imagining a better reality.

Essentially, this film serves as an exercise in imagination as a basic human right. We released the film at the end of last summer, but had to shelve it at the beginning of the war. It just didn’t feel like the right time, with the initial shock we were all in. But now, with the growing interest of people to know the background of what’s happening in Israel/Palestine and as a tool to push back against certain groups who want to believe the universe was created on October 7th, we feel the timing is right to bring back its release.

The occupation can take many things from us. But what’s the one thing they can never take? Our ability to imagine. And what’s the first step towards creating a better reality? Imagining a better reality.

—Rami Younis

Lyd screened in Australia in March as part of 2024’s Palestinian Film Festival.

**********

Lauren Collee is a writer, researcher, and educator working at universities across Sydney. Her work has been published in The Baffler, The Los Angeles of Books, The Sydney Review of Books, Overland, Kill Your Darlings and more.