To quote Woody Allen: “At the very early stages of our new relationship, when lust reigns supreme… we couldn’t keep our hands off each other” (2020, Apropos of Nothing). He is of course referring to his wife Soon-Yi Previn, the adoptive daughter of his former partner Mia Farrow. In 1992, Farrow discovered nude photographs of 21-year-old Previn in then 56-year-old Allen’s home. Their love affair is one that continues to perplex and perturb, as it somehow transgresses assumptions about decency and descent, parentage and progeny. Perhaps the greatest transgression of all is the fact that, to this day, their marriage stands the test of time.

Echoes of the Allen-Previn story are heard in notorious French director Catherine Breillat’s new provocation, Last Summer. The film is an invitation to live precariously through protagonist Anne (Léa Drucker), a seemingly put-together woman who falls apart upon the arrival of her stepson Théo (ingénu Samuel Kircher).

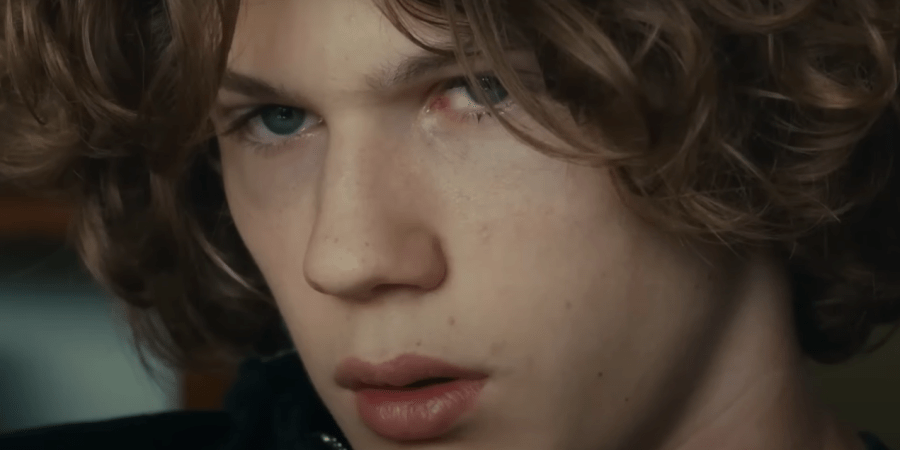

“Haven’t you grown,” Anne says to the shirtless 17-year-old in their first moment together on-screen. Théo bears a striking resemblance to the so-called ‘most beautiful boy in the world,’ Björn Andrésen, who starred in Luchino Visconti’s Death in Venice in 1971. Kircher was cast for the role when his older brother Paul dropped out at the last minute. Théo’s hair is wet; his clothes are strewn all over the room. “Yeah, it’s cool,” he replies with total indifference. This is clearly a teenage boy speaking to an adult.

Théo has returned to the family home in provincial France to spend the summer with his father, Pierre (Olivier Rabourdin), and his new family. This modern family also includes Pierre and Anne’s two Asian daughters, Angela (Angela Chen) and Serena (Serena Hu), who were adopted after the white married couple struggled to conceive children. Early in the film, Pierre is accused of adopting them in an attempt to clear his conscience of the ‘mess’ he made raising Théo. Can he offset his failures as a father by giving it another go? Was the subconscious urge to repent the driving factor behind starting a family with a second wife?

The adoption of the girls brings to attention the conventions of parentage, which are abstracted in cases where the state is responsible for deciding custody of the child. The same goes for Théo, of whom Anne is parent only by default. Interestingly, Anne is introduced from the first scene as a lawyer working in child protection. One young girl who reappears throughout the film is gradually steered into the foster system based on Anne’s evaluation of her being unsafe with her father. In her professional life, Anne is an arbiter of family law. It is with this set-up that Breillat makes her scathing uppercut. Before long, Anne crosses the proverbial line with her stepson. The story reads much like a tired porno: MILF-STEPMOTHER SEDUCES BARELY-LEGAL BOY TOY.

Woman and boy embrace in a moment of forbidden passion, sitting over an iPhone screen, Théo’s anime playing in the background while they kiss. It’s all so pubescent. During filming, Breillat prompted Drucker to imagine herself as the teenage girl in Éric Rohmer’s 1983 Pauline at the Beach. Their attraction to one another is telepathic and left largely unspoken.

Breillat asks us to consider how quickly personal principles evaporate when tempted with pure fantasy. A thousand questions emerge; has Anne been unfaithful to her husband before? How long has she been eyeing her stepson? Has she justified it all within herself? Is she not afraid of the consequences? Is this self-destruction something she has consciously chosen?

Anne describes this emotional paradox as her “vertigo theory,” where a fear of falling meets a fear of wanting to fall. Perhaps there exists in every person a desire to destroy that which is cherished most. With her home in crisis, everything is at stake for Anne, including her marriage and the custody of her daughters. She is faced with no other choice but deny, deny, deny. After being accused by her husband, who has caught wind of her affair from Théo, Anne defends herself with a double entendre: “You’re so easy to manipulate. Even a child can do it.” She chooses to multiply her deviousness, claiming that this is a vicious lie concocted by a troubled teenager. Before long, Anne is a part of a case not unlike the ones she oversees in her professional life.

Unfortunately, the built-in irony which Breillat deploys reads as overly premeditated at times. It’s not enough for a middle-aged woman to want to trespass from her marriage and sleep with her husband’s son, as she must also be an advocate of the law who works in child protection services. She of all people should have known better, we are constantly reminded throughout the film. It’s especially cynical to imagine the sexual predator in even the most well-intentioned of professions. But it is righteousness, rather than depravity, that Breillat is rebuking so adroitly in Last Summer. Nobody is beyond reproach, especially not the people who profess and claim to practise morality on behalf of the law.

With this, Last Summer makes a wider cultural accusation about the hypocrisy of policing and regulation when it comes to sex. The film is an indictment of the sexual politics that have formed around the protection of a fictional child. From the ongoing contentiousness of reproductive rights and women’s sexual liberation to advocacy against child sexual abuse or the risks of youth accessing perverse material, the child is always at the centre of discussions about sex. What effect does this have on actual children? Are they safe from harm?

Like all indulgences, time is not on Anne’s side. It’s all in the name: Last Summer. Is this a nod to Anne’s encroaching old age, emphasised by Théo’s youth? Or maybe it is a reminder of the finality that is promised by the seasons, of which passion shares some likeness. Heat is only enjoyed in the knowledge that the temperature is about to drop. Total pleasure was never meant to last.

Last Summer is now showing across Australia as part of the Alliance Française French Film Festival. It is due for a wider Australian release later this year.

**********

Charles Carrall is a writer and critic from Sydney, Australia. He makes up one half of the podcast, Vanity Project.