The creative process is rarely triumphant in the films of Michel Gondry, the French writer-director with a knack for transforming chronic, subconscious unrest into ebullient dioramas and dreamscapes. It is always fruitful, however—often to the point of overripe excess. In 2006’s The Science of Sleep, the unhatched visions of a socially inept calendar designer, Stéphane (Gael García Bernal), cause him to develop a pair of outsized papier-mâché hands. In Gondry’s music video for Björk’s ‘Bachelorette,’ the singer finds a blank book in the forest that miraculously writes her memoir into its own pages, bloating to the cumbersome dimensions of a suitcase. Soon, she is trapped on a stage with it in her arms, forced to live out a pantomime of premature stardom.

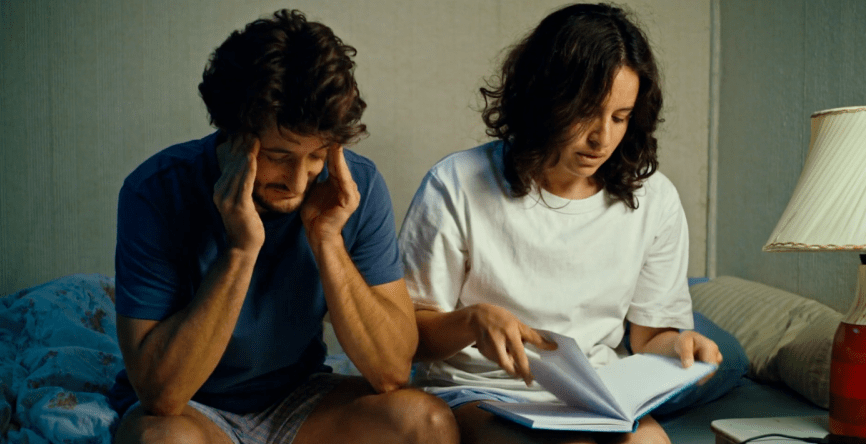

The Book of Solutions, Gondry’s latest and most personal film, broaches the uncontrollable vitality of artmaking with a similar mishmash of the spectacular, playful, and pathetic. Inspired by the post-production purgatory he incurred after filming magical realist romance Mood Indigo (2013), this surreal comedy begins with failure: a meeting of film producers who reject the four-hour offering of naïve, albeit depressive, director Marc (Pierre Niney). When this leads to a coup by his associate—the bearded traitor Max (Vincent Elbaz), who agrees against Marc’s wishes to whittle the oblique epic into a marketable object—Marc responds by kidnapping the film.

For Marc, it’s as simple as unplugging a monitor and absconding with his small, reluctant crew to the house of his patient aunt Denise (Françoise Lebrun). Here, in the foothills of the Cévennes, his collaborators (read: hostages) will recut the film, eat aubergine gratin, and, when he decides to flush his psychiatric meds, endure Marc’s midnight outbursts of quixotic delusion. In one embarrassing begging session, Marc demands that his assistant—Sylvia (Frankie Wallach), who is trying to sleep—open her laptop to somehow summon Sting to join the film’s soundtrack. The fact that the artist goes on to make a dazzling cameo is testimony to Gondry’s unshakable drive to indulge his weirdo heroes. Obsession, however silly, has an alchemical function, and dreams always count for something.

It feels strange that Gondry’s name is most recognisable for his direction of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)—the kooky yet ultimately devastating romance in which a dour loner, Joel (Jim Carrey), uses sci-fi technology to erase all memories of ex-girlfriend Clementine (Kate Winslet). The film was penned by Charlie Kaufman—a writer who shares Gondry’s interest in self-destructive fetishes, but not his utopian whimsy. Where Gondry’s own narratives involve people unexpectedly cohering around art’s by-products, Kaufman’s usually follow tapeworm-like trajectories, as he sends his characters—Philip Seymour Hoffman’s terminally ill theatre director in Synecdoche, New York (2008), for instance—only deeper into interiority’s abyss.

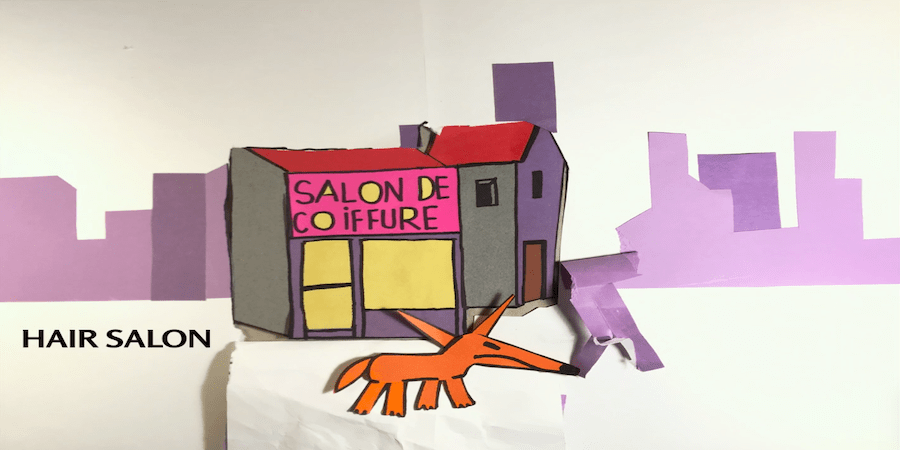

Denise’s house is a teeming parable for the collective subconscious of its inhabitants, rendered in painterly, living colour. Inside, Marc finds a book he’d made as a child, which on its cover announces itself as ‘The Book of Solutions.’ Like Björk’s book, its contents are void. But, in Gondry’s realm of fatalism and fabulism, blank pages are always promises, and Marc goes about filling his with orphic symbols, which correspond to makeshift rules for art and life. “You have to start a project like you start a car in winter,” is one of them, while Marc’s favourite motto is that one must learn by doing. The book is less a manual of answers than an archive of experiments, rituals, games, and incantations (which, Gondry posits, may be the same thing). For Marc and Gondry alike, moments of crisis call for simplicity, and this often involves a deferral to pen and paper, the child’s first medium. The paper’s flat surface moves Marc to launch into feats of procrastinatory fancy, making a stop-motion sequence about a hairdressing fox which recalls Gondry’s own past pipedream that an unwieldy cut of Mood Indigo could be salvaged by an animated intermission.

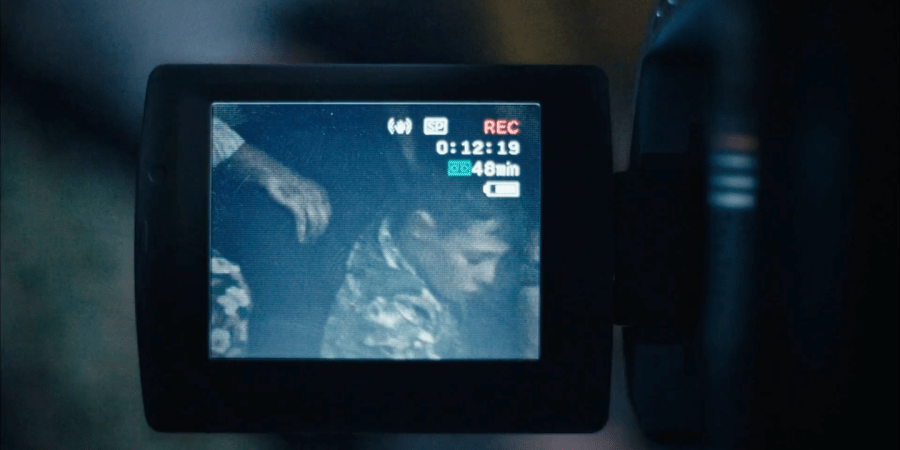

Like Marc’s personality, The Book of Solutions is controlled in its absurdity. It is driven by Marc’s abiding narration—composed and lucid despite his distress, slowed as if he is both a child panicking and an adult soothing a panicking child. Gondry’s dialogue is precise but has a spontaneous flair, as the film revives, at points, a deadpan mockumentary style, albeit with greater warmth and unpredictability. Genuine epiphanies bloom through the film’s uncynical awkwardness. Marc decides to conduct the orchestra himself for his movie’s score. He does so with an attempt at live composition. This entails pawing and poking the air and, eventually, wriggling his ass, trying to prompt the confused professionals into improvisational communion. Partway through, Sylvia, half-heartedly filming, begins to shut off her camcorder, but editor Charlotte (a perfectly wry Blanche Gardin) stops her: “No, stay. Watch.” The boundary between humiliation and revelation has been crossed.

Wonderfully, the inventions that Gondry’s stories centre upon are devoid of market value, geared instead towards satisfying eclectic urges and settling personal scores. Like domesticated cats, his protagonists arrive at the doorsteps of rivals, friends, and unlikely lovers with proverbial dead birds in their mouths. In The Book of Solutions, Marc offers an “editing truck” to the overworked Charlotte and his shy crush Gabrielle (Camille Rutherford), as an apology and a seduction in turn. However unnecessary and ill-received, these attempts indelibly bind creativity to sociality. The artist’s possessed egomania is only further proof that art is always, in large part, for others.

The ‘solutions’ of the film’s title quickly become compulsive. Compulsion and repetition: more of Gondry’s archetypal modes. One of my favourite music videos by the director is for Kylie Minogue’s ‘Come Into My World.’ In it, Kylie’s reality is ruptured by a humble mistake when she drops a parcel on the street upon leaving a French laundromat. She picks it up and circles back, where she’s thrust into an infernal circuit, duplicated each time she reaches her initial station (along with passers-by in Yves Klein blue boiler suits). Unperturbed, the Kylies move together, twirling around street poles and appearing almost to touch, despite living on different layers of film stock. Another favourite, for the White Stripes’ ‘City Lights,’ features a hand illustrating lovelorn lyrics on a foggy shower screen, racing the lines’ impermanence and slicing into the residue of previous images. In these tableaux, as in The Book of Solutions, compulsiveness is drawn gently, recognised as a cause of harm (as when Marc throws a mobile phone into the sink, or plates of spaghetti down the stairs, with wild motions inherited from childhood), but also as the drive behind communication itself. Gestures, like rolling snowballs, form tentative worlds.

When Marc can’t find something he needs, he yells its name and expects it to come (“Le scotch!” when the tape goes missing). He is besotted by his elderly aunt, with an intensity that combines childish idolatry, a grown nephew’s desire to repent, and a teenager’s forays into sexual perversity. Niney, navigating the tightrope registers of the infant-adult, is outstanding. He thrives in the context of the hilarious, heartrending choreography of care and refusal that ensues with the film’s poised supporting cast.

Sometimes, Marc is dormant and rigid, lying prostrate on the first bed he finds with unblinking, haunted eyes. In other moments he exudes confidence and buoyancy—the not-blinking reading as another childhood game; life is so exciting that he couldn’t bear to miss any of it. When it seems to be passing too quickly, in imaginative ecstasy or exasperation, the film is literally sped up, so that a ghostly Marc flits across the frame.

In The Book of Solutions, Gondry casts his director not as an ultimate creator, but as a gopher-like, though nevertheless prescient, voyeur. At one point, Charlotte and Denise scheme to host a screening of the film for the latter’s 75th birthday party, in hopes of coercing Marc into finally facing it. Yet, at the party, he stands beside the screen and opts to film the audience in a slow, curious pan. Many of them are fast asleep, snoring and drooling. He lists them, introducing us to the community and justifying their inattention: the butcher, Antony, is tired from chopping and carving all day; the baker, Emile, needs rest to soon return to work. His attention settles on a schoolteacher, a hairdresser. Marc, so often bitter and distraught, is here simply meditative; the director’s work becomes real when the cinema is most akin to a bedroom, a nook for fatigued bodies and drifting psyches.

The Book of Solutions is now showing across Australia as part of the Alliance Française French Film Festival.

**********

Indigo Bailey is a Tasmanian writer and editor living in Naarm/Melbourne. In 2023, she received the Island Nonfiction Prize for an essay about rain sound. She has written for Island Magazine, The Guardian, Voiceworks, and Kill Your Darlings, among other publications.